In 1991, X-Men #1 sold more than 7 million copies. The first issue of a then-unheard-of *second* X-Men title, written by Chris Claremont and drawn by young superstar Jim Lee, it remains the best-selling single issue of a comic book of all time. Yet for as much as X-Men Vol. 2 #1 marked the beginning of a new era of even higher commercial viability for Marvel’s best-selling comic book characters, it’s often forgotten that it also marked the end of another era. Two issues after X-Men Vol. 2 #1, Claremont leaves the franchise whose course he charted, along with a murderer’s row of artistic collaborators, for the previous 16 years. More significantly, the new era launched by X-Men Vol. 2 #1 also marked the end of one of the most creatively rich — if also divisive — eras in X-Men history, as Claremont and his collaborators tore the team apart and slowly put it back together, deconstructing the X-Men to examine what made them tick.

This often gets overlooked when discussing the ’91 relaunch. The tremendous sales success, the popularity of Jim Lee, the way it opened the door to trading cards, the animated series, an entire licensing style for merchandise, all tend to sidestep the fact that it came about via as commercially driven an overhaul of a creatively rich period — an overhaul that came at the cost of arguably the most important creator in X-Men history — as the imminent “From the Ashes” relaunch. Which is to say that sweeping away the old (and often creatively rich) in favor of the new (and potentially commercially rich) is a time-honored X-Men tradition.

But are such relaunches inherently bad? Can good ideas get smuggled in alongside the blatant desire to goose sales? Is there hope for “From the Ashes”? Let’s take a look and see what history tells us.

The ’91 Relaunch

The X-Men are no strangers to new creative directions coming in to shake things up — often at the cost of the previous one. We can go all the way back to the mid-1960s, when Professor X died and the FBI told the X-Men to break up so Cyclops could be a radio DJ and Jean a bikini model. The most famous and/or impactful, of course, is the debut of the All New, All Different X-Men in 1975’s Giant Size X-Men #1, which led to a whole new bunch of characters becoming X-Men in place of the previous creative direction of “reprint old stories to keep the title protected.” But neither of those instances really reflect the modern understanding of the creative relaunch, when a new creative vision is executed by a new wave of creators with the distinct intent to do something completely different from what was done before — with that “completely different” usually being, on paper, more sales-friendly.

The first true instance of that is the aforementioned relaunch of the X-Men titles in 1991. Uncanny X-Men and X-Factor received new creative teams, alongside, for the first (but certainly not last) time, a brand new X-Men title. Those three joined the already-released X-Force (which was itself an overhaul of the old New Mutants title) to form a new, distinctive line of X-books (Wolverine’s solo series and Excalibur were also around, but kind of existed in their own little pockets, though Alan Davis’ return to the latter coincided with the wider linewide relaunch, giving the whole thing an additional boost). Though Claremont was technically still a part of the line, being the credited writer on the record-setting X-Men Vol. 2 #1, he would leave the series with issue #3. Moreover, technically Claremont was already gone by the time X-Men Vol. 2 #1 hit the stands, having handed in his scripts for the first three issues before leaving, calling them his severance package — the royalties on those three issues reportedly paid for his house. While Marvel didn’t exactly trumpet it as such, it was very clear: The days of Chris Claremont being the chief guiding voice of the X-Men were over. Taking his place were a pair of young, superstar artists with little writing experience under their belt.

It would be hard to argue that the stories that followed the big shakeup in 1991 — plotted by Whilce Portacio and Lee, scripted, somewhat ironically, by Claremont’s former collaborator John Byrne (and later Scott Lobdell) — are creatively richer than the work Claremont was doing before the relaunch. While energetically illustrated in the popular style of the time and responsible for introducing a handful of fan-favorite characters, the plotting and pacing show the inexperience of their creators. Meanwhile, the years preceding the ’91 relaunch are, in hindsight, some of the most creatively rich of any era of X-Men, as Claremont pushed Uncanny into new types of stories and deconstructed the very concept of the X-Men. At a time when Uncanny X-Men was consistently the best-selling comic in America, months would go by without a group of characters calling themselves X-Men even appearing in the book. Claremont was in the midst of doing some fascinating work, but if you just wanted to see a consistent group of characters wear colorful clothes and punch some bad guys, you were left wanting.

Which is partially why, despite the relative creative energy of that pre-relaunch era, most fans still look back fondly on the ’91 relaunch as the start of an exciting new era, and not a self-serving attempt to milk even more money out of the franchise at the expense of its chief creative architect and the overall quality of the stories. Also contributing to that sentiment is the fact that that the sheer sales success of X-Men #1 meant it was the entry point for a lot of new readers, making what followed a nostalgic favorite. It’s also down to the fact that the creators — during Portacio and Lee’s tenures and especially after, once they left to help form Image Comics — were largely doing stories that could be described as “Claremont lite.” If you weren’t paying too much attention (or weren’t around for the real deal), you may not have noticed what was missing. It also helped that the post-relaunch versions of the characters were directly adapted for the animated series that launched in 1992, cementing them as the definitive versions for an entirely new (and even larger) audience. Despite the commercial motivations driving it, there’s a reason this era of X-Men continues to be mined by Marvel, including by the upcoming “From the Ashes” relaunch.

So Long, Morrison (Or, Who Is Xorn, Anyway?)

After 1991, the ever-growing line of X-Men comics went through its fair share of creative launches and relaunches (including one short-lived and ill-fated relaunch driven by the return of Chris Claremont to the X-Men). But the next most creatively rich period came from writer Grant Morrison in their New X-Men (the retitled second volume of X-Men that had bought Claremont his house). Riffing in their own way on the tropes codified by Claremont, Morrison in turn pushed the X-Men in bold new directions, cracking open new thematic avenues and pushing the characters to explore new areas of their personalities. Gone were the colorful costumes, replaced by more utilitarian leather (not unlike that worn by the characters in the Fox films launching around the same time). For the first time, mutants were presented as a fully formed subculture, with characters who fell outside the traditional “hero,” “villain” and “everyone else” buckets.

That this left some readers uncomfortable and unhappy almost seems like a proof of concept for what Morrison was trying to do, perhaps never more so than with their interpretation of Magneto. Stripping away the complicated nuance Claremont spent a good chunk of his run developing (though in fairness to Morrison, the ’90s, in general, had done a lot of that work for them already), Morrison’s Magneto was revealed to have been Xorn, one of the mysterious new characters Morrison had made central to their run. From there, Morrison’s Magneto assembled a new Brotherhood of Evil Mutants and laid siege to New York City, a return to pure arch-villainy that, in tone, at least, wouldn’t have seemed out of place in the ’60s.

When Morrison left New X-Men, what followed immediately wasn’t a pure relaunch as we think of it today. New X-Men continued for a time before reverting to the simple “X-Men” moniker, the characters continued wearing their more toned-down looks, and concepts Morrison introduced, like secondary mutations, hung around. But Morrison’s Magneto was almost immediately repudiated (in part by Claremont, in a spinoff title he was writing at the time), the result of a convoluted retcon involving twin Xorns, one of whom was revealed to have been posing as Magneto posing as Xorn during Morrison’s run for … reasons. But the true post-Morrison “relaunch” came a few months later, in 2004’s Astonishing X-Men #1.

Written by then-nerd darling Joss Whedon and lushly illustrated by John Cassaday, Astonishing X-Men is a clear rebuke of Morrison’s post-superhero take on the X-Men. In the opening issue, the X-Men re-don their colorful costumes and step out into the world with the stated goal of representing themselves as traditional superheroes once again. Yet for as much as Morrison’s run was (and is) well-regarded by many and fans were sad to see them leave, Astonishing was embraced as well, selling like gangbusters. Cassaday’s art was clean yet lush, Whedon’s script’s snappy and kinetic (if a bit boilerplate), a far cry from the rich, dense texts packed with ideas of Morrison. Astonishing X-Men was a series designed to appeal to the broadest possible audience (of comic book readers), and it did that remarkably well.

Blue & Gold

It doesn’t happen often, but sometimes, the desire by editorial to return to something safe and familiar is greeted with excitement by fans rather than trepidation. The mid-2010s weren’t kind to the X-Men. With cinematic adaptations increasingly driving the directions of the comics and the X-Men’s movie rights tied up in a non-Marvel studio, the print X-Men were largely put on the backburner in favor of the box office blockbuster Avengers and, later, an ill-fated attempt to make the Marvel Studios-controlled Inhumans the new “hated and feared” minority in the Marvel Universe. As a result, the X-Men entered a creatively fallow period of atypical stories and characterizations, including an increasingly zealous Cyclops, the X-Mansion moving to the demonic realm of Limbo and a war with the Inhumans over a poisonous cloud.

When it was announced that a back-to-basics relaunch was being helmed by Marc Guggenheim (known for creating an expanding universe of DC Comics-based live action shows for the CW), the news was generally greeted with relief by fans. The stories that followed in what has become known as the X-Men’s “Color Era” (thanks to the way the title of each X-Men book had a color designation) are, in hindsight, not great. They are relatively bland and derivative, reading like cover versions of ’90s stories (many of which were, in turn, cover versions of Claremont stories). The scripts are competent, but unexciting, the art similarly lacking the punch of a Cassaday or Lee. Plenty of fans were relieved simply to see something familiar after years of “IvX” nonsense, but it’s hard to argue this was a creatively rich period for the X-books.

From the Ashes

Technically, the Color Era came to a close with the launch of House of X #1 and the beginning of the Krakoa era (though it came after the dual water-treading exercises of “Age of X-Man” and Matthew Rosenberg’s Uncanny X-Men run). While it continues to have its detractors, it represents one of the most creatively exciting eras in X-Men history, probing the metaphors at the heart of the X-Men to depths not seen since the Morrison days, offering a variety of storytelling styles across its titles unseen since the ’91 relaunch, and digging into characterization and longform storytelling like no one since Claremont. In Pepe Larraz, it had, for a time, the kind of powerhouse artist that provides a visual foundation for these kinds of relaunches. It was a font of creativity that rivaled (and, some would say, surpassed) the X-Men at their height.

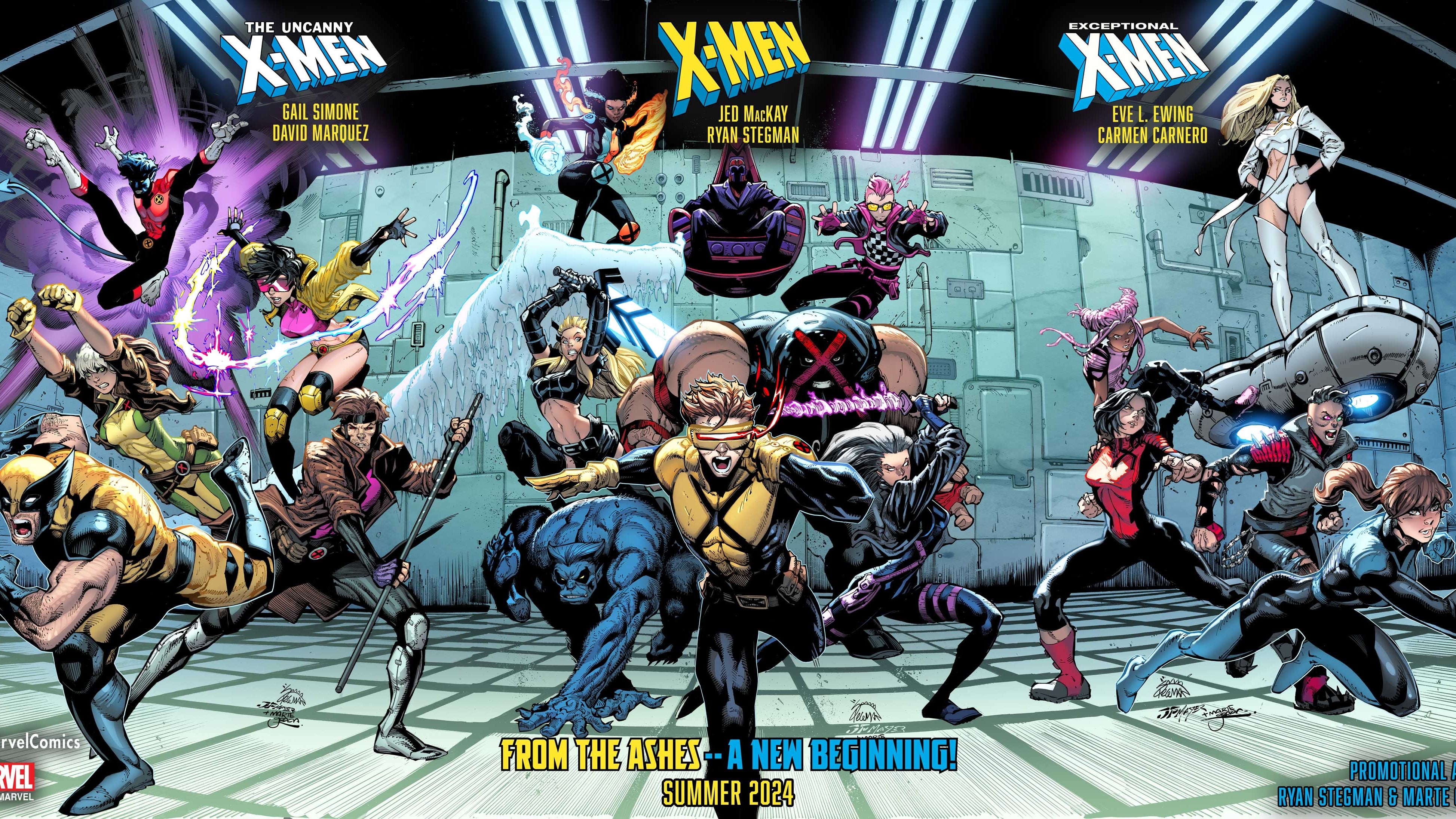

But every creatively rich period is just one commercially driven relaunch away from ending, and now we stand on the precipice of “From the Ashes.” Like the ’91 relaunch, Astonishing X-Men and the Color Era, it is clearly designed to present a more comfortable and broadly appealing iteration of the characters, one that will, with eventual hindsight, likely mimic what is coming in the form of the MCU’s version of the X-Men. That it comes at the expense of such a distinctive and creative (if somewhat floundering) iteration of the line, an iteration that deeply resonated with many readers, is a shame.

But it’s worth remembering that this is hardly the first time the X-Men have been relaunched in the interest of presenting a more sales-friendly version of the line. That even amid the corporate-driven appeal to the bottom line, good stories can still emerge, new readers can discover the characters and become fans, with the full tapestry of what came before — both good and bad — now more available to them than ever before. “From the Ashes” may not be for you — despite its clear attempts to capture as broad an audience as possible. Yet solace can be taken in the fact that these things are cyclical, that the wheel of serial superhero adventure comics always turns (at least until the point at which it becomes unprofitable). It’s happened before, and it’ll happen again. Today’s “From the Ashes” will eventually be supplanted by tomorrow’s Krakoa or New X-Men or Chris Claremont. That’s not much, but it’s something.

Austin Gorton also reviews older issues of X-Men at the Real Gentlemen of Leisure website, co-hosts the A Very Special episode podcast, and likes Star Wars. He lives outside Minneapolis, where sometimes, it is not cold. Follow him on Twitter @AustinGorton