In July of 2000, the film X-Men became the surprise hit of the summer. More than anything else it signaled the beginning of the era of the comic book movie blockbuster. Over on the print side, things weren’t so bright. The X-Men books felt stagnant and they were nothing like the effortlessly cool film that was in theaters. Marvel’s big move was to look to the past and bring back Chris Claremont after eight years away from the mutants, but it only made things worse. The days when the letter X would just print money were over and fans weren’t interested in hearing the same stories again and again. The X-Men needed innovation, they needed a transformative moment, they needed something as exciting and transcendent as 70’s Claremont or 90’s Jim Lee. The books needed a whack on the side of the head.

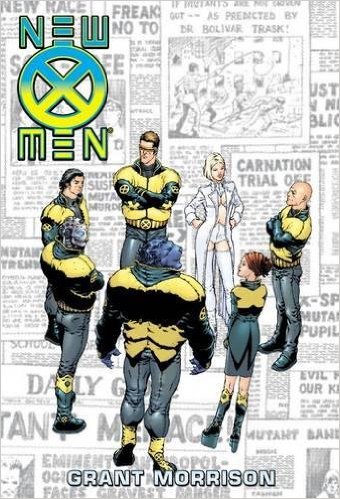

Grant Morrison’s New X-Men was the injection of creative steroids that the line needed. Morrison could see past the self-imposed barriers of what an X-Men book should be and thought about what it could be. His creativity wasn’t locked down, it was unleashed and dripping off every page. Dr. Roger von Oech talks about this creativity in his seminal book A Whack on the Side of the Head. The text describes the Ten Mental Locks on creativity and how to break them. As we look towards the ResurrXtion era of X-Men, the next big opportunity for a transformative change, I want to look back at how Morrison broke those mental locks and what the X-Writers of tomorrow could learn from him.

Mental Lock #1 – The Right Answer

All through our education, we are judged for one thing, getting the right answer. It’s a rigid, unforgiving structure. There is only one way to solve an equation, or spell a word, or write a cursive Z. This runs completely counter to what creative thinkers need to do. In the world of X-Men of ’00 there was one way to do things, harken back to the heyday of Claremont with art from whoever was the next Jim Lee or Rob Liefeld. It was a plan that worked for years and made a lot of people very rich, but it was well out of gas by the time Morrison took over New X-Men in 2001.

Morrison broke out of focusing on “The Right Answer” by finding the second right answer. He found an amazing solution by not accepting conventional thoughts on how X-Men should work. His pitch for the series, titled “Morrison’s Manifesto”, reversed the conventional thinking by asking what made X-Men cool in the first place? He wasn’t OK with keeping the slavish devotion to continuity at the expense of good storytelling, He wasn’t OK with maintaining the status quo. He wasn’t OK with a sprawling cast that was only there to satisfy fans who were going to “read the book and bitch about it NO MATTER WHAT”. He wasn’t afraid to break away from a conventional X-Men story, and that made all the difference.

Mental Lock #2 – That’s Not Logical

For a world populated by aliens, time travelers, and twenty-foot-tall genocide-bots, there is a bizarre amount of focus on making sure the X-Men are logical. Morrison was unconcerned with logic. He ensured that the story he was telling had an internally consistent logic to it, but he wasn’t going to go out of his way to explain how a mummudrai works. He knew he wanted the first villain to be Xavier’s evil twin and formed the story he needed to make that illogical idea work. By being abstract, by playing with ambiguous concepts like “the cool guy” or “evolving Sentinels”, Morrison ensured he wouldn’t fall into the trap of being “logical”.

Mental Lock #3 – Follow The Rules

Dr. von Oech says “Creative thinking is not only constructive, it’s also destructive. Often, you have to break out of one pattern to discover another one.” This is the revolutionary idea that rules, especially rules that just grew out of a culture of success, can and should be broken. Morrison saw so many opportunities to break rules, that it was amazing he got away with it. The cover of his first issue was a statement, not just because of artist Frank Quitely’s stylish design, but the fact that there wasn’t a traditional costume in sight. It was an evolution of the black leather look that Blade, The Matrix, and Singer’s X-Men had cemented in the pop culture of the time. They were sexy, militaristic jackets with yellow highlights. It was a new superhero uniform for a new century, and it looked like something Wolverine would actually tolerate wearing.

This isn’t to say every broken rule is a good thing. In the wake of 9/11, Morrison was adamant about revealing Magneto for what he believed he was. Morrison said,

“What people often forget, of course, is that Magneto, unlike the lovely Sir Ian McKellen, is a mad old terrorist twat. No matter how he justifies his stupid, brutal behaviour, or how anyone else tries to justify it, in the end he’s just an old bastard with daft, old ideas based on violence and coercion. I really wanted to make that clear at this time.”

While in the vacuum of New X-Men the plot works well, it didn’t jive with the Magneto comic fans had grown to love or the thoughtful revolutionary in the films. Sometimes there are rules that shouldn’t be broken, like having Magneto systematically murder hundreds of innocent people, but worse than breaking the rules is being too afraid to. It took a lot of work, more than it ever should have, but Magneto moved on from the character Morrison made him. Something broken can be fixed, but the destructive process of creative thinking needs to be allowed to take place.

Mental Lock #4 – Be Practical

Like following the rules or being logical, we are told throughout our lives to make practical decisions. While there is a time and a place for practicality, the inception of a creative process isn’t it. The practical creator doesn’t ask “what if”, they simply dwell on what they already know to be true. We saw this in full force in the X-Men books in the late 90’s, they capped off the decade with a Chris Claremont plot thread that no one was begging to be tied up when they covered The Twelve. It was a practical choice, sure, but it was the furthest thing from innovative you could imagine.

Grant Morrison thought differently. He asked what the X-Men would look like viewed through the lenses of an audience who was most familiar with the Brian Singer film. He obliterated the status quo by outing the X-Men to the world. It wasn’t practical, in 2001 most Marvel heroes still had secret identities but it was a bold move that opened hundreds of innovative story lines. The X-Men could be more than secret soldiers; they could be ambassadors.

There were failures along with the successes, Grant proposed killing Rogue and replacing her with a version that was closer to the movie or X-Men: Evolution, but that’s part of the process. Practicality needs to happen; it just needs to happen later in the development process. Restricting creativity in the early stages, to only things that are practical, limits the development of ideas. Let ideas be birthed unrestrained and narrow the focus when the time comes to implement them.

Mental Lock #5 – Play Is Frivolous

If necessity is the mother of invention, then play is the father. Taking time to do something unrelated to the task at hand can help build connections and innovations you never thought possible. Morrison had played in other areas long before he came to Marvel for New X-Men. In his Manifesto, he describes taking inspiration from his days in a punk band and you can see that influence in the way he transformed the mutant race into a counterculture. It was no longer just hated and feared, it was admired and feared. Closer to comics, Grant Morrison hadn’t read the last twenty years of X-Men before pitching his run. He played in other areas, dealt with other types of stories, and brought that influence with him. By harnessing the power of play he made something new with X-Men.

One way to stimulate play is to restrict yourself. Mark Rosewater, head designer of Magic: The Gathering, is well known for wording this as “restrictions breed creativity”. By limiting your tools you force yourself to discover new ways of doing things. Grant made a rule for himself, no resurrections. Without that crutch he had to retool his stories, he couldn’t use the recently dead Colossus so he was forced to develop the concept of secondary mutations and give Emma Frost her now iconic diamond form. These were changes that would have never occurred if Morrison wasn’t forcing himself to play around the restrictions he imposed.

Mental Lock #6 – That’s Not My Area

People want to exist in their own bubble. They want to limit their exposure to things that are new, things that are different, things that are difficult. They want to carve out their niche and live in it. That’s where the X-Men were for years. There was a simple definition of what the X-Men were, how they acted, and who was on the team. It was long past the Claremontian glory days where the status quo shifted every 18 months. There were a ton of different titles in the X-Men line, but there wasn’t much difference between the books. The editorial staff was afraid to move outside of their comfort zone.

Grant Morrison wasn’t. By 2001 he had written The Invisibles, he had written Animal Man, and he had reinvented the JLA. He wasn’t afraid to branch out into places that weren’t his area because he was always changing what that area was. By living outside of a comfort zone, Grant saw the obvious solution to the X-Men’s problems. Their biggest fans weren’t kids obsessed with a cartoon or action figures, they had grown up and it was time for the X-Men to do the same. Morrison told mature stories with the X-Men, he let characters grow, and he never let anyone stay comfortable for more than six issues.

Mental Lock #7 – Don’t Be Foolish

In matters of importance, we are told to be serious, but that’s not the right way to be creative. Playing the fool, asking the seemingly obvious questions, and challenging the norm can generate more creative inspiration than one would expect. A fool also makes a point to laugh at themselves, and by examining the sources of humor they can find important nuggets of truth.

Morrison took things that had become foolish, like Wolverine mentoring young girls, and turned them on their head with the character of Angel Salvadore. He was willing to take the ultracool, suave, stereotype that Gambit had become and crank it up to eleven with Fantomex. He took the played out, horrible future trope to its natural extreme by making a Revelation pastiche. Morrison was willing to be foolish with the X-Men and revitalize a series that had long since gone stagnant.

Mental Lock #8 – Avoid Ambiguity

Cyclops, and by extension X-Plain the X-Men co-host Jay Edidin, has a saying “It’s good to be precise about these kinds of things.” This speaks to the importance of precision of language, but in creative endeavors, that’s not always the best thing. Ambiguity allows a creator to fill in the blanks, to find their own unique solutions to problems. Morrison’s Manifesto, which was the template for the entire X-Line mind you, was not a concrete document. It didn’t lay out what a world where mutants were admired would look like, it simply presented the concept and allowed other to do their own twist on it. It’s how we got amazing things like the X-Statix being reality show stars. It’s also how we got Stacy-X and the X-Ranch so it isn’t always perfect.

Morrison stretched that ambiguity to his explanations in the book. You never get a clear-cut answer on how involved Sublime was with everything or if Ernst and Cassandra Nova were the same person, and that is just fine. The fact of that matter is, nothing about this world where the main character has foot long knives in his hands makes any sense. By trying to explain it in a rational manner you lose some of the magic. It’s why no matter how hard Al Ewing tries, time in the Marvel Universe will never actually work. The ambiguity is a function of the storytelling. Pull too hard on the strings and the whole sweater will unravel.

Mental Lock #9 – To Err Is Wrong

We are trained to think success is good and failure is bad, but that isn’t exactly true. The X-Men books were wildly successful for twenty odd years before they suddenly weren’t. The writers and editors became complacent in their success and stopped moving and changing. Every right idea is eventually the wrong one, but sometimes it is already too late by the time you realize it. The only reason Morrison was needed to fix the X-Men is because their success broke them.

On the flip side, messing up isn’t bad. You can learn more from mistakes than you can from most successes because mistakes force you to re-evaluate what worked and what didn’t. A mistake that Morrison made, one that served his story well, mind you, was making mutants a very numerous race. They were a thriving minority, not just a handful of gene freaks. This put the core concept of the Marvel Universe at risk and couldn’t continue as the default for the life of the franchise. Out of that, Marvel came up with the Decimation, a decision that led to the next generation of status quo shifting books.

Mental Lock #10 – I’m Not Creative

Studies have shown that a key difference in creative people and uncreative people is what group they think they fall under. If you don’t think you are creative, you probably aren’t. Creative confidence drives innovative work more than anything else, and Morrison had it in spades. Between reshaping the Justice League, forcing Animal Man to break the fourth wall, and creating a character who was literally a sentient street, Morrison oozed creativity. His manifesto was dripping with confidence. He knew he was the man who could solve all the X-Men’s problems, and he did.

At the dawn of the new X-Men ResurrXtion I hope writers, artists, editors, and everyone involved in X-Men take a minute to reflect on the lessons of Morrison and von Oech. The fans have spoken, they don’t want a run-of-the-mill, generic X-Book, they want something that will astonish them. The comic book market is saturated with innovation and the X-Men can’t afford to be left behind. By breaking down their mental locks on creativity, the sculptors of the X-Books can breathe new life into the franchise. They can resurrect the line and restore it to its’ former glory. They can make X-Men feel new again.

Zachary Jenkins co-hosts the podcast Battle of the Atom and is the former editor-in-chief of ComicsXF. Shocking everyone, he has a full and vibrant life outside all this.