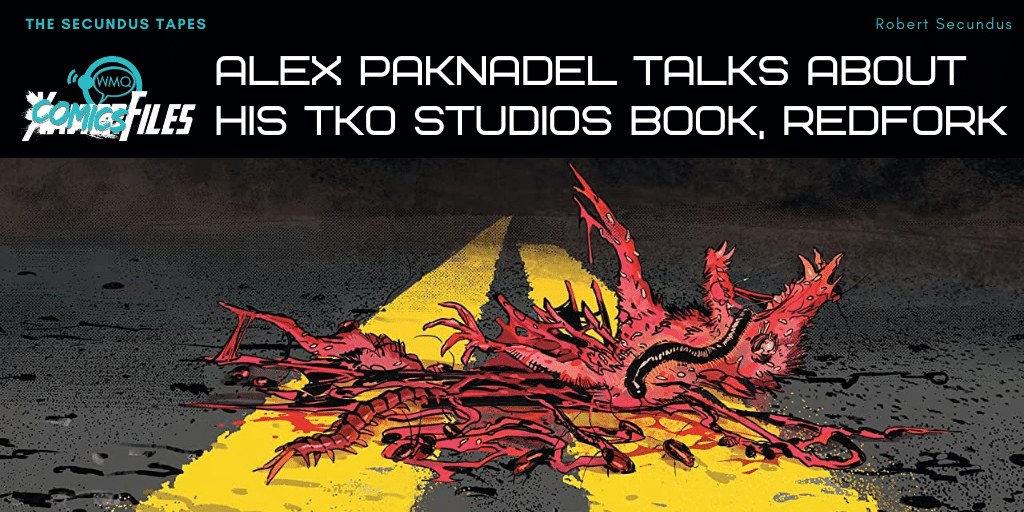

Redfork is a six-issue miniseries/six-part graphic novel by writer Alex Paknadel, artist Nil Vendrell, colorist Giulia Brusco and letterer Ryan Ferrier. It follows Noah as he leaves prison and returns to his Appalachian hometown, where he discovers sinister forces both without and deeply within that community. It is available now from TKO Studios.

This interview with Paknadel was recorded Nov. 24 and has been edited and abridged for clarity and space.

Robert Secundus: Today I’m talking with Alex Paknadel about Redfork, a book about the opioid crisis, economic despair, and cosmic as well as capitalistic horror, all seeping into an Appalachian town.

So before we get into the story of Redfork in detail, I have a couple of questions about approaching a TKO title, because I think the formal constraints of that whole line are really interesting and unique in the industry. Did you approach this book differently than you would a serialized miniseries or a non-serial graphic novel, considering that TKO is kind of always both at once?

Alex Paknadel: Yeah, absolutely. I went to ComicsPro in Portland, which is like a retailer consortium, in February, and I was handing out ashcans of issue one. And they weren’t complete, so there are various retailers around the U.S. who have a very, very different version of the first issue. Reason being, I cottoned on halfway through to the fact that I didn’t need to pace it like a monthly periodical. So you [normally] have that BKV, Geoff Johns thing of, you need two holy shit moments per issue — which is great when you’re releasing on a monthly schedule, because it keeps [interest sustained— which is not to say that you can’t be kind of formally and conceptually inventive within that kind of framework. But those are the demands, right? You need to whet people’s appetite, what have you. And I realized about halfway through, and went and rewrote accordingly, that I could do this as much more of a slow burn. So if a normal kind of structure is like a sin wave, I could do this more like a roller coaster, where I spent the first issues just ratcheting up the tension, ratcheting, ratcheting, ratcheting. That was really interesting — where do you put the issue breaks when you’re doing that? It was a very different approach. I don’t think I nailed it necessarily, because I think it’s so new. But after a while it certainly felt luxurious: Alright, I can really kind of take my time with this. And crucially, as well — speaking to TKO, there are a couple companies out there, Vault’s another one, where if you say, “Guys, like, can I get another couple pages?” They’ll generally go, “Yeah, yeah, fine, you’re fine, go.” Which is amazing.

RS: All TKO books are set at exactly six issues standard, right? But then you’re saying that within that structure, there’s a flexibility there in the page count where you can change what those chapters look like to fit the story?

AP: Oh yeah. If you really want to decompress, or if you want to give something more room to breathe. So, you know — I tend to be quite a plotty writer. With this and Giga in particular, I’ve had a lot more latitude than I’ve enjoyed previously. I don’t know why, but for some reason, 2020 was the year I’ve been given a lot more latitude in terms of, “OK, you know what, you want a splash page to really let this breathe? OK, you can have that.” I just try not to invoice for them!

RS: My assumption reading these books has always been that the TKO approach would be far more constrictive, far more formally constrained than other kinds of miniseries given that each is exactly 6 issues; but in fact, it seems to be the opposite, that it’s a really malleable form, which is really, really counterintuitive to me.

AP: The linewide editor is Sebastian Girner, who’s a very accomplished writer in his own right. He understands that kind of “Oh man, if I had two more pages, I’d really be able to swing for the fences.” He gets that. And they’re lucky, I think, in the sense that they’re very well capitalized, so they really have that freedom. If they really want to squeeze another couple pages out for a chapter, they can.

RS: I feel like people should be paying attention to that, because it feels to me like a variety of stories and a variety of genres have been really successful with this model recently. They succeed by bringing together amazing creative teams and just giving them the flexibility to do what they need to do.

AP: I think it’s interesting that — Sorry to dwell on this, but just super quick — I was talking to my dad, and he’s an old-timey kind of comics guy. But, you know, he just got a Marvel Unlimited subscription, right? And he’s been reading all of Marvel chronologically, because he collected from the early ’70s to the early ’80s. And one of the things he said to me was, “Oh, man, you know the 10-cent price point, right?” It’s really interesting what happened, because Marvel Comics #1 in 1939, was, what, 50 pages, or something like that for 10 cents. Fantastic Four #1, which came out 22 years later, was also 10 cents. But what they did was, they reduced the page count. And it wasn’t really until the late ’60s where they stopped reducing the page count and let inflation take over, so it went up to 12 cents, 25 cents, 50 cents, and then where we are now for four bucks up. What really struck me about having a conversation with him was — oh man, this 20-22 page model is not some kind of adamantine optimal delivery system for storytelling! It’s a result of inflationary pressure. It’s economics that dictate that length, not a creative decision.

RS: There’s probably a parallel there with the recent success of streaming in this new golden age of television, right? Where you have the serialized model that gets fit into this one format, that is just dictated by economics, and how you sell the ads, and how you cut up airtime. And now that we’re chucking all that away, we see what people can do when they can just sit down and write a 20-minute, or a 90-minute, or an 80-minute TV show, whatever they need.

OK, I think I’d like to turn to Redfork properly. And first, I want to try to situate it in with a few of your other works. Because it’s the first book of yours I’ve read that I think is just straight horror, but it seems like that genre has been on the edges of your work before. Evelyn Waugh-ish grotesque satire is always edging into horror, and I think Friendo fits into that genre. Dystopian science fiction is always edging into horror, and Arcadia is clearly in that category. So it feels like you’ve been interested in horror for a while, and I’m wondering what it was about Redfork that led you to just plunge straight into it.

AP: This is going to be a really prosaic response, and I apologize in advance. Genuinely, my hand to God, I just couldn’t get a horror book picked up until now. I’d always pitch them. But you know, it’s the usual thing, right, of “I want to see four pitches.” And they always went for the world-buildy stuff. And that’s fine, you know, that’s my meat and potatoes. That’s what people, if they do like my stuff, that’s generally what they like me for. [Redfork] was the first one I managed to get across the line, but I’ve been pitching them since 2015. It was just the first one that hit. But I mean, really — I know, it’s a bit gauche to pigeonhole yourself, but I do consider myself first and foremost to be a horror writer. That’s where my loyalties lie. That’s what I like to read. That’s what I like to consume. My writing pollstar, my platonic ideal of a perfect script is The Fly. I always come back to that, not beat for beat, but certainly how that made me feel. I’m always trying to replicate that (and falling catastrophically short, but you know, hopefully there’s a nobility in the attempt).

RS: I do think readers can see that, again, that impulse for horror in your other work, because it always does feel like, at least of the comics of yours that I’ve read, it feels like they’re always on the verge of horror; or, at the end, they embrace the horror. The final beats of both Friendo and Arcadia are deeply horrifying on several levels.

AP: … Thank you?

RS: Ha, it is intended as a compliment! The other throughline in your work is, I think, social commentary and the satirical impulse. So I’m wondering: How do you approach these worlds in these stories — or, I’ll put it this way. It always feels like these worlds cohere. They exist functionally as interesting settings on their own. And yet, the social commentary element is always very apparent. So how do you balance that, how do you ensure that they stand up on their own, while still holding up the mirror to the world that you wish to hold up?

AP: I think — this is gonna sound again, horribly gauche, but I see that as due care and attention, right. I was discussing this with Dan Watters, just in terms of what purpose certain musical and cultural forms serve in terms of response to trauma. So the punk rock response is a very important one, but I think it’s largely — and I know Dan will disagree with this, will be able to point to a million examples of very sophisticated and very subtle and nuanced, you know, The Clash, for instance, right, this is not cookie cutter — but in the main, my view is that punk is documentary in the same way that, I think, a lot of late ’80s hip-hop was documentary. It was there to provide a beautifully crafted but very immediate and tactile, visceral response to certain cultural stimuli. But I think the challenge with that [approach] is that it gives it historical specificity. “God Save the Queen” is largely, you know, it’s the three-day week, it’s the British recession in the 1970s. And it’s very much hitched to that mast. And it’s immovable. And this is probably the height of arrogance, but I want my stuff to have a longer shelf life. So really, it’s a pragmatic decision. I want to unmoor it from the very specific. I want to make it more general and more about human tendencies than about specific events. Sorry to go this dark, but I always find it interesting there was, in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, a brief flurry of cultural responses to it. And they were necessary, I think they were absolutely necessary. They were cathartic. But it wasn’t until sort of 5-10 years later that you started getting the stuff that really addressed it — even something like Batman Begins is a very interesting, a very kind of nuanced response to it. Someone’s really gone away and held each facet up to the light and gone, “OK, I think we’re dealing with this trauma.” I’m not comparing anything I do to that. It’s not that polished, but certainly that’s what I’m trying to do, efface that trace of any immediate social or cultural comment connotation and make it more universal, if I can.

RS: Well, it seems like horror is a genre very suited to that, if you look at what is considered the earliest examples of horror, something like Frankenstein or Dracula. They’re so rooted in the anxieties of their moment, and yet, because they evoke that same terror today, they get at something universal, something that transcends that period, even though they’re dialed right into their own time.

AP: And also they’re so open-ended, right? I mean, you talk to two people in a room. One person will tell you that Frankenstein is absolutely the terror of the industrial age. It’s the terror of the enlightenment. It’s, you know, Promethean knowledge and the horrors that it will give rise to, culminating in the Holocaust. Another person will tell you, “Oh no, it’s basically Mary Shelley’s open letter to her husband calling him out for being a deadbeat dad.” And I think, if you can efface those traces, and if you avoid them becoming overloaded signifiers, you can have that sort of plasticity, where, yeah, it does absorb all these different readings. And it’s not about being evasive. It’s not about being puckish. I’m not trying to play tricks on anyone. I just want these things to be sort of burnished services. So people get to bring their own readings.

RS: Redfork, I think, does speak to these broader anxieties, about economics, and our increasingly terrifying environmental reality, and poverty, and all of these problems that we’re all facing, that are only going to get worse. But it’s dialed into the specific region of Appalachia. I’m wondering why you chose Appalachia for this story?

AP: Honestly — don’t get me wrong, I could equally have set it in, if I filed the serial number off, in West Yorkshire or North Wales. But I don’t think that it would have had the same reach. Which is a sad thing to say, but I just don’t think it would have. I may well be wrong. And I’m sure my friends in Wrexham are about to send me dirty messages. But I think what’s interesting about that area is that it’s at the confluence of so many shearing economic forces. And there’s an argument that Appalachia is what the future looks like. It was an interesting place to research for all sorts of reasons, but I think what I found really interesting about it was that this is an area that in the early 20th century had a very, very, very strong union movement. And to the extent that — and again, this is cursory reading, but my understanding is that the term “redneck” may derive from red scarves that were actually used by mining unions. I don’t know whether it’s more rooted in a sort of Methodism than it is Marxism necessarily, but it has a strongly socialist or proto-socialist kind of history, though it’s now ineluctably Trump country. How does that happen? And my understanding is that the same thing has happened in northern Italy. So in these industrial towns where the promise of globalization didn’t trickle down to them — I’m fairly explicit in the book — when those areas get hollowed out, when people’s mineral wealth under their feet is stolen, that creates a vacuum, and that vacuum will be filled. And I say this as a, whatever, a metropolitan liberal elite, or a coastal elite. But I think one of the reasons why I set it there was that it’s, from everything that I’ve read, and from everything I’ve seen, that it’s one of the places where, for want of a better expression, liberal global subjects, like me, took our eye off the ball.

RS: One of the things that prevents this from reading to me like liberal elites looking down on the region is the care and attention to the humanity of the characters involved, who are all drug addicts, murderers, ex-cons and sometimes, much worse, CEOs. I feel like the typical “coastal elite” approach would be to make the hero stainless, make him the one guy who has never touched drugs, or to make the relatable characters people who have stepped back from these things, and so lead the reader to snobbily look down on everyone else. But that’s not the case here. All these people are very broken and damaged and harmed by their surroundings, but that’s not in tension with the fact that they have this deep human dignity. And so I’m wondering how you approach forming broken characters and ensuring that their personhood shone through, given these horrors?

AP: Thank you very much. That’s really gratifying to hear. So first of all, I mean, I knew what I wanted to achieve with this conceptually, and I spoke to a couple of the guys in my writers studio, Dan Watters and Ram V, about it. And the one piece of advice they gave me, before I even put pen to paper was — normally I write theme out, which I think is why a lot of people — not a lot of people, but you know, a couple people — tend to like my world-building. But with this, because I was setting it in a very established context, both of them, [Watters and V], took me to one side and said, “Look. With this, you have to write character out, you have to write these characters first.” And then basically imagine that you are crafting these pins, and you’re going to put them at the end of an alley. And you’re going to take this opioid crisis, and that’s the bowling ball, and you’re going to roll it at them, and then see what happens. So writing character out.

But sort of allied with that, I also had an in, in as much as, I mean, I am a recovering alcoholic and drug addict. I had that to draw on. That was a long time ago, and I’ve been off everything for well, well over a decade. But I can certainly remember the most dissipated, despairing hours, feeling very strongly within that abjection, like, I’m a human being, and I certainly don’t think I would have recovered, I don’t think I would have managed to get my act together if I didn’t think there was a kind of kernel of basic decency underpinning all of that pain. And here’s the other thing, right, is I know, from personal experience, I know, from the experiences of friends who’ve been through similar situations, that nobody, nobody has an addiction because they’re happy. They’re medicating themselves through some pain. And yeah, that can be squalid. And it can be incredibly selfish, I mean, biblically selfish, but at the heart of it all is a human being suffering. I kept that uppermost in my thoughts at all times, so every time I felt like I might be getting kind of tropey or stereotyping, I just tried to pull myself back to that.

RS: In addition to the CEO, the capitalists, there’s also a faith healer and preacher as the central antagonist. You were talking before about the shift from Methodisty socialism to MAGA America. And I’m wondering if you could speak to your choice to make faith healing so horrifying and preaching so central as a force preying upon these people.

AP: I have to speak around it to an extent because I don’t want to give too much away. I was reading a lot around cultic behaviors. I wasn’t looking to any specific denomination, or any specific behavior. I watched a bunch of documentaries to prepare for this, and read a bunch of stuff, and I didn’t really want to go down the handling-snakes route. Because I think, again, that’s a stick that Appalachia is beaten with. I don’t think that’s a representative experience. But certainly, I think — and this is something that I think we can all relate to — the character of Gallowglass is simply the better life around the corner, tantalizingly out of reach. But it’s simple. And I think that’s the thing that defines the populist era, right, is someone comes along, and — I am not for one second asserting that Europe’s shit doesn’t stink in this regard. My country is in the grip of a kind of populist convulsion. It’s shameful. It’s disgusting. But ultimately, it’s someone coming along and addressing a very, very complex situation, which is the price of globalization, and saying, “It’s really simple, we’ll do this.” And the closest kind of analogy I could think of was a traveling miracle healer. It’s the monorail salesman guy from The Simpsons, right? These people terrify me. They’re mountebanks, they’re con men. It doesn’t matter how enlightened or how advanced we think our societies have become; we always seem to hit a point, (and it’s usually economic), where we become acutely vulnerable to these people. And so what I thought, setting it in this area, and setting it with this character, and embodying it in this figure of Gallowglass — what I tried to do was address it in microcosm. Rather than dealing with it on the global level, which you could do in something like The Expanse (and they do it very, very well), I can just take this one town and this one character and go, “OK, I’m going to hold this up to the light.”

RS: I (and many people I know) have some experience with similar kinds of charismatic, laying-on-of-hands-type people, as well as less Protestant, more Catholic organizations that are similarly culty — and I know that some of these groups do have roots in some parts of Europe, but it feels like an especially American thing, the religious preacher who just says, “I understand that you’re hurting, your wallet is hurting. But just trust me and Jesus will solve your problems.” And you ultimately don’t escape the system causing the problems, but rather give yourself over to the system in another form. If i try to unpack the deep structure of Redfork, that’s the horror — it’s the horror of these people trying to turn away from the thing controlling them and giving their own lives to just the same thing in another form, but even worse, even more monstrous.

AP: Don’t get me wrong, Europe certainly has its sort of recalcitrant religious traces. We have the same thing — but also you can just replace “religion” with “the state” and you still end up with the same problem. This idea that secularism shit doesn’t stink is nonsense. But yeah, absolutely it’s an out-of-the-frying pan, into-the-fire situation. But in terms of those sort of charismatics — you can see it in Tony Robbins, who presents himself as an anti guru: “I’m not your guru. I’m just gonna shout at you until you get better.” It’s the Gordon Ramsay principle, tough love. But it’s all the same thing. It’s all, follow the program and everything will be fine. But of course, reality is much more stubborn than that. It’s magical thinking, it’s this idea that some sort of attitudinal realignment will somehow change the universe. Don’t get me wrong; you have to meet reality halfway, you have to do the work, but I think one of the — you know, it’s interesting, my wife is an academic, and she’s working on a project on self-help narratives and how they’ve spread throughout social media. And one of the things that all this stuff does, either intentionally or not, is it places responsibility for failure squarely on the individual’s shoulders. Society doesn’t bear any responsibility whatsoever. You just didn’t want it enough. You got a bad attitude. That’s just not true! There are deep structural barriers that are preventing people from having decent lives, right?

RS: A couple days ago, I very suddenly realized, like, I just snapped into awareness of the fact that the term “manifest,” in its self-help terminology sense of “manifesting something,” had become so commonplace that when I see it on Twitter, I no longer have to consciously go, “Oh, they’re talking about this weird The Secret shit.” The word just means that now. And that was a terrifying moment, realizing just how much that culture had penetrated just the average person’s consciousness.

AP: This is where my wife’s research is going. You don’t get these self-help grimoires anymore, right? Do you remember when TED Talks used to be about stuff!? Instead of just, like, “I drew an eye on my palm and then the next day, I had a car!” When did that happen? It seems incredible. And yet, it seems to be when all these support structures and institutions are crumbling. And then all of a sudden, it’s, “well, all you need to do is have a positive attitude, and everything will turn out for the best!” No, it won’t! It helps. But, you know, you can’t change the laws of physics.

RS: Weird, forced segue: Speaking of physics, laws of nature, etc., I’d like to ask about a trend, or a throughline between Redfork and other recent examples of environmental horror (I’m thinking in particular of Old Gods of Appalachia, which is, if you haven’t heard of it, a serial podcast that I think you’d find very interesting — but also I’m thinking more broadly of works like the horror film The Apostle). Something I’m noticing is that more and more, these works of horror no longer see the Earth or nature as something in complete opposition to monstrous exploitation, but instead see the land itself as hostile and horrifying and corruptive in some way. It’s a change in how we think about the environment, being afraid of this thing that we’re exploiting, even as we become more desperate to save it. So I’m wondering if you could speak to that a bit — why you and your work see something already monstrous lurking within the Earth, in the depths, in addition to our own monstrous exploitation of it.

AP: It’s an interesting one, this. You’ve got the Timothy Morton track, and you’ve got the kind of Nick Land track. So you can either go down the sort of Fanged Noumena approach, where you’re veering into quasi-fascism, where there is a blood-and-soil relationship, and it’s always trying to eat us, so we might as well feed ourselves to it, right? Or there’s the more benign Timothy Morton hyper-object approach, which is much more holistic and much more Gaia focused. I think that’s the track that I tend to stick with, is this idea that — I don’t think nature is monstrous. I think it’s monstrous when it’s treated as an object. So when human beings don’t view themselves a part of a network of interdependencies — and this is like, man, going right back to Spinoza and Heidegger and stuff — if we instead view the Earth in instrumental terms, yeah, it rebels. Absolutely. It’s funny; you look back on ’60s hippie culture, and there’s a strain in it of the Whitman-esque stuff, and the ideas of the early Romantics, that nature is inherently sort of beneficent, benign, which is nonsense, right? The flip side of the sublime is fear, is terror. Again, I can’t go too far into it without giving away too much of Redfork. I can’t tell you why I did it, but there is an implied contract between the forces of rapacious capitalism and, quote unquote, “the Earth” in the story. It seems like a strange alliance, unless you consider the possibility that it’s neutral, right? The Earth isn’t this kind of hippie-dippie thing; if you lay down and sleep in the middle of the desert, chances are something will try and eat you. That, to me, is just pragmatic. But by the same token, it’s recognizing that there is an element now of — I’m going to get into the long grass here — but planetary husbandry. There was an interesting point in the Douglas Copeland novel Girlfriend in a Coma, which I thought was really interesting. At the end of that novel, the characters have this sort of religious experience. And at the end of it, they’re told by this kind of angelic figure, “Look, you’re the stewards of the Earth now. You’ve taken over so many natural processes, through mass farming techniques, agriculture, cattle raising; basically the Earth is yours. It’s your responsibility. Now, if you fuck it up, it’s on you.” And I think broadly I’m in agreement with that. So one of the things that I was trying to communicate with Arcadia was this idea that technology can’t be alienating, right? Technology is a reflection of humanity. And so if technology is a reflection of humanity, we can’t blame it when it turns on us because we made that. And I think with Redfork (and I’m thinking this through in real time), I think what I’m doing is broadly the same with nature. When nature turns on us, I don’t think we can blame it. We’ve taken ownership of nature now. So it’s us turning on us again.

RS: Stories like this push against our false assumption of a dichotomy between ourselves and nature. Yeah, of course, of course nature will be monstrous if we approach it monstrously, because we’re part of it.

AP: That’s one of the things that I always thought was interesting about Animal Man. Why can’t he reach into the bio-morphic field and become an accountant from Delaware? That’s an animal. You know what I mean? Or a Vegas waitress. Why can’t you reach in and get that? But again, we see ourselves as separate from the landscape.

RS: I’ve got one more question for you, a question I ask everyone as we wrap up. For people who read Redfork and are hungry for more — what are three other works of art of any kind (books, comics, movies, albums, poems, whatever) that you think rhyme with or contrast with the book? Or would just be interesting next-reads, next-watches? Things that you’d like people to put in dialogue with the text?

AP: I’m leery of jumping straight into this, because I don’t want to suggest that they’re clean comparisons, because then I’ll seem like an arrogant prick. But I can tell you what was in the mix. If I sort of genuflect and say, “Well, these are directly [influential], it’s a derivative work,” then I’ll feel a little bit less out on a limb with it. I think There Will Be Blood; frankly, there’s a lot of that in there. Just in terms of the intersection of — I don’t want to call it religion, but that sort of spirituality and resource exploitation.

There’s also a book about the opiate crisis called American Pain. Christopher Sebela recommended I read it before I started this. And that’s very, very interesting. It’s just about the harm, the instrumentalization of drug addiction in the U.S., that informed an awful lot of this.

And there was a book by Pamela Petro called Sitting Up with the Dead that I would really recommend. She’s basically gone all around the American South, collating oral folk history and oral folktales. And it’s an absolutely incredible work. She’s basically gone state by state and just collected local legends, and recorded many for the first time, these stories that have been passed down over generations. And I think with Redfork, what I did with that was utterly synthetic, obviously. I mean, look at me, I live 5,000 miles away, but I took what I thought was quite a syncretic approach. On one level, there’s giving people what they want, right? One of the people that I have consulting on this book is a local, West Virginia writer called James Maddox who is a good friend of mine. And I was outlining the book to him over Skype, and he was like, “You’re doing cryptid shit, right?” Almost world weary. “You’re doing cryptid shit.” And I was like, “…Yeah, …OK.” But then again, it’s a question of how you serve it, right? This isn’t hubris, by the way. I’m not saying I think I did a phenomenal job or anything, but I tried not to lean into the Mothman kind of thing. You know, not that there’s anything wrong with that, but I just wanted to give people something that hopefully they hadn’t seen before.

RS: I hadn’t thought of the cryptid connection until you mentioned it (though now I see it’s there), I think because the kind of body horror in this book is rare in cryptid narratives. If you were trying to not make that connection too apparent, well, it wasn’t apparent to me until just now.

AP: But it’s absolutely part of the recipe. It’s just, again, trying to file off as many serial numbers as possible. One of the things that I found really instructive was looking at the response to — it’s a completely different setting, but one of the things that made me say, “OK, I really do need to consult with writers who know this area, and I need to be extra careful in how I approach this,” was the stuff that was coming out about 8-10 years ago, the misery porn that was coming out of Detroit. And I thought that was very, very instructive, man, because there came a point when we had a lot of misery tourism, both real and fictional. And then eventually, people who lived in that area were going, “We live here! These are our lives, man!” [in the voice of the misery-tourist]: “Oh, you know, isn’t it remarkable that the United States has a third-world country embedded in the middle?” “It’s not! We’re a community, it’s not ripe for anthropological study, these are real lives.” And I watched that response and just how rightly offended those people were, and I just tried to map that onto what I was doing with this. Like, I hope I haven’t — and don’t get me wrong, I’m sure I’ve messed up plenty. But I hope that there’s, as I said right at the beginning, I hope there’s a merit, at the very least in the attempt. I really did try to be as respectful as I could.

Robert Secundus is an amateur-angelologist-for-hire.