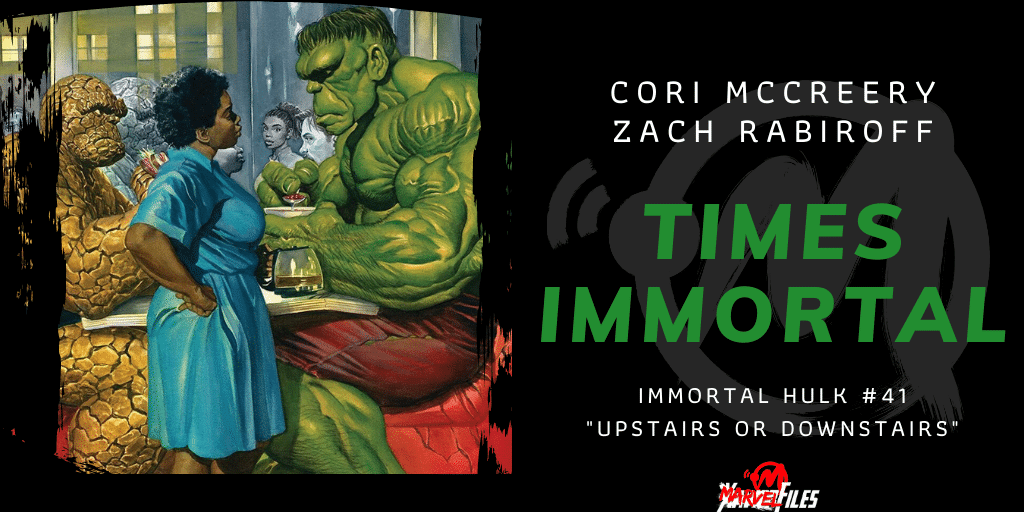

Hulk vs Thing, meal to follow in Immortal Hulk #41, written by Al Ewing, pencilled by Joe Bennett, inked by Ruy José and Belardino Brabo, colored by Paul Mounts, and lettered by Cory Petit.

Zach Rabiroff: [Lights up on the stage. Zach is in his own clothes again now. A suitcase is by his side. He looks glumly at the door, with the name ROBERT SECUNDUS – CO-WRITER painted on the glass window.] Well, Cori, I guess this is it. The time has come. My last installment as your co-writer on Times Immortal, never to be seen again. Why, I bet you won’t even talk about me when Rob comes back next issue. Yes indeed, you’ll all just move along with life like these little fill-in pieces never even happened, won’t you? Well, let me tell you something, you big-shot comic critics: maybe I’ve got other places to be, you ever think of that? And let me tell you something else: you won’t have Zach Rabiroff to kick around anymore, that’s for sure! No, I’m not crying!

Cori McCreery: Uh Zach, we agreed on a rotation now, remember? You’re only moving cause you have your own fancy office now. Now shut up and let’s get back to work.

ZR: I…really? I still have a job? Well, this is wonderful! It’s a miracle! It’s…hey, is there anyway I can unsend a priority mail package to Rob, because I may have made a big mistake, and it might be filled with snakes.

World’s Greatest

ZR: Well, this is new. We’re used to seeing opening epigrams in this series that range from 17th century English epic poets, to country music lyrics, to the Old Testament, but this is the first time we lead off an issue with an actual excerpt from Holy Writ itself: a pair of panels from Jack Kirby and Stan Lee’s Fantastic Four #5. Across two brief images, Johnny Storm peruses the finest in graphic literature, the debut issue of The Incredible Hulk, and snarkily compares the title character to his equally brutish-looking friend (and frankly, the fact that they started publishing a Hulk comic in the Marvel Universe literally days after Banner’s tragic accident always seemed kind of tasteless on Martin Goodman’s part, if you ask me). It’s a seminal moment at the dawn of the Marvel Age, really: the first in-story appearance of a Marvel super hero in the comic of a different Marvel super hero. And, oddly enough, it’s an exception to the rule, because it pretty explicitly takes place outside of any coherent Marvel universe. Johnny is talking about the Hulk as a fictional character, the kind of Frankenstein-esque monster so ugly and absurd that to compare the Thing to him is a grotesque absurdity. Within a few months, that border between distinct universes would start to break down, and Ben Grimm would have his chance to go head-to-head with the Hulk in Fantastic Four #12 (the very first Marvel crossover issue), and then, especially, in the epic, two-part brawl of issues 25 and 26.

But I think that by putting these panels at the start of the issue, Ewing is setting them up as a kind of ur-text for the Hulk/Thing relationship, at least as Ben Grimm sees it. For Grimm, the Hulk is a challenge and a rival: someone big enough and tough enough to beat him, and therefore a threat to the only quality Ben really believes he has (the cliffhanger ending to Fantastic Four #25 finds Grimm muttering himself in shock, “He beat me!! That big, brainless, muscle-bound creep beat me!! It…it never happened before!!”). But he’s also, more subtly and insidiously, a lurking fear – a vision of what he could have been, and might someday become, if not for the tiniest quirk of fate in their respective misfortunes. Ben has to show that he’s tougher and better than the Hulk because that’s the only way he can reassure himself that he will never be the Hulk, even if he would never admit that reality to himself. And by my reading, at least, that informs much of what goes on between the two of them later on this issue (which we’ll be talking about a little farther down, no doubt). So, what’s your read on this, Cori?

CM: Well that’s a lot deeper than I was expecting. For me it was “Haha Johnny called Ben ugly.” But really, it’s a good call-out. Here’s this monster that’s feared and hated, this behemoth that everyone is terrified of, but what exactly is stopping Ben from being that? And the answer to that, is that Ben has a support system to prevent that. He has friends who are there for him no matter what, which is something the Hulk has not really had for much of his existence (no Rick doesn’t count, Snapper Carr wannabe). But that is something that Hulk is starting to build, which leads us into the actual opening of the issue.

ZR: Wait, wait, wait. I was under the impression this would just be 2,000 words of stemwinding about deep-cut Marvel history. I was not told there would be an actual comic book I had to read. But, yes, the opening of the issue. That would be an all-too-brief prologue of Charlene McGowan, taking matters into her own hands in a secret Arizona safe house. Charlene has been a kind of moral through-line in this series, ever since she proved her capacity to resist the influence of Xemnu because of her own hard-won reclamation of her identity and sense of self. It’s never stated outright (Ewing is too subtle of a writer to beat a hammer quite that loudly), but my read has always been that her assurance unwillingness to give in to manipulation or coercion are closely tied to her place as a trans character in this story. Much like the Hulk, she’s waged a battle to take possession of her own mind and her own body, and she’s not going to give it up without a fight. She’s also not going to see those things taken away from others, which I think accounts for her solitary last stand here. So even though this is all we’ll see of her this issue, it still felt like a quietly thrilling scene to me: a check-in with a hero in a book that doesn’t always have one.

CM: Charlene is the reason I started reading this book in the first place, so it’s nice to see her getting even the briefest of spotlights. And what you just said about her identity and her struggle to reclaim it both rings true and resonates with me. It reminds me of my own personal ethos. I do the hard things, I do the fighting, I take the punishment, why? So that others don’t have to. If my fights, if my work saves a single person from having to suffer in a way that I have? That means that I did what I needed to. It’s the credo to which I live my whole life, and it’s why I have always, and always will identify hard with the paladin archetype. Charlene is like me in that respect, and many others. If she can make life better for one person, she’s going to do her best to do that.

A Grimm Turn of Events

ZR: But enough of this nattering about history and character and authorial intentions. Let’s get to what everyone came here to see: fight! Fight! Fight! Fight! And you know, Cori, after last issue’s delightful pun-bedecked cliffhanger, this didn’t disappoint. Not just because, as it turns out, Joe Bennett draws a mean, heavyweight boxer-looking Ben Grimm, but because (as always in this series) it was really about the fight going on inside the characters’ heads. In this case, there’s a harrowing tension in the Thing’s unwillingness to face the obvious fact that the Hulk is in no shape to fight at all. It’s the trouble with a long and sordid personal history, I suppose: Grimm is so convinced based on past experience that Banner is the arrogant, destructive monster out to prove his strength that he can’t see their roles have at last been reversed. It’s the Lower East Side street kid at his worst, so focused on the need to prove himself to jerks and bullies that he never notices when he’s become the bully himself. So it’s no surprise to see Ben’s mortified shock when he realizes, at last, that he’s been effectively pounding his fists on an overgrown baby. And it’s equally unsurprising to see him, without ever really apologizing in so many words, patch things up in the only way that New York boy knows how: with a hot dog and a beer. Grimm may be a lot of things, but he’s still a mensch. Cori, what’d you think of the big fight?

CM: The “big” fight was mostly just sad and pathetic, which is what was the intention. This wasn’t ever going to be your classic Hulk and Thing slobberknocker (though we do see Thing knock some slobber out of Hulk in a very literal and disgusting sense). This is a drained and childlike Hulk, not smart enough to know he’s overmatched. And like you said, it takes Ben much longer to realize that Hulk is currently outside his weight-class than it should. Really it takes Joe telling him to stop beating up a kid for it to click. That’s when we get one of our only moments of body horror in this issue too. How’d you like Joe fixin’ his broken arms?

ZR: At this point in the series, I feel like I’ve expended every possible variation of “Joe Bennett draws body horror real good,” but: sweet God, that is some wonderfully hideous imagery. And I love the contrast between Joe’s alarmingly blasé attitude toward his own grotesque metamorphosis, and Ben’s nauseated “Holy Hannah!” Forty-one issues in, we readers are pretty much like the Hulk himself, so used to these twisting limbs and warping faces that we don’t even notice them as something out of the ordinary anymore. It takes someone like Ben Grimm to remind us that the Hulk is still a creature out of the realm of the surreal.

Job Hunting

ZR: The real (kosher) meat of this issue comes in the heart-to-heart between Grimm and Joe Fixit at a Coney Island hot dog joint. And it’s all because Al Ewing does what Al Ewing does best: mining continuity to use its raw materials in strange and wonderful ways. In this case, the scene hinges on the climactic arc of Mark Waid’s (really quite good) Fantastic Four run. In that series, Ben Grimm dies in battle, only to be retrieved from heaven by his mourning teammates, who come face-to-face with his creator — a deity who bears a more than coincidental resemblance to the late Jack Kirby. So I wasn’t being all that facetious when I called the Lee and Kirby era holy writ: Ben Grimm has seen the face behind the veil, and it was chewing a stogie.

Now, anyone who’s read, uh, anything I’ve written will guess that I’m an easy mark for reminders of Ben Grimm’s Jewishness, but the way Ewing uses it here is especially interesting. As he has the Thing tell it, that trip to death and back was directly responsible for the religious reawakening that he underwent shortly afterward, studying with a rabbi and having a belated bar mitzvah after four decades of subtextually-expressed faith. And it’s also where he picks up the metaphor of the Biblical Job, suffering miserably and undeservedly in the face of an uncaring world. It’s a tremendously moving scene to read; Grimm recognizing, and admitting to himself, that he’s been mapping himself onto that metaphor the wrong way all this time. He isn’t the suffering, unlucky Job. Nor did he dodge that fate because of any virtue of his own. He dodged it because he had friends, and love, and a network of support from the people around him right from the beginning. His job isn’t to rage against God; it’s to reach out a hand to the less lucky schmoes right in front of him. And that’s the other side of the Lower East Side Jewish tough kid: the guy who’s willing, when it comes right down to it, to be a friend.

CM: Zach, I’m going to be 100% honest with you here. Reading that paragraph just now gave me literal chills down my spine. The reason that I’m drawn to this book and to Ewing as a writer in general, is because he’s so good with both representation and these little personal moments. He allows you to connect to characters in a way that not a lot of writers can. One thing I actually wanted to ask you about relates to this scene actually. I don’t have a lot of religious background myself, as my mom was never particularly religious when she was raising me, and whatever little bit I had I eschewed as an adult. But I remember being told somewhere, somewhen, that the concepts of Heaven and Hell were vastly different in Judaism than they are in Christianity. Does this bit with Ben do some disservice to that idea?

ZR: You’re quite right about Judaism and Christianity having pretty distinct outlooks on the afterlife, but I wouldn’t say that Ben’s experiences are particularly at odds with the Jewish view – or, at least, no more at odds than with the Christian view, considering that neither the holiest of holy spheres as a homey art studio. In a nutshell, Judaism tends to view the soul’s passage after death as a kind of journey to various destinations defined by their degrees of connectedness to the Divine Presence. How that journey progresses, or what the stages are, differs between rabbinic schools of thought. Ewing in particular tends to draw from the more esoteric and mystical traditions of Kabbalah and pre-Kabbalistic thought: we’ve seen that in this series, where the figure of Metatron is taken from the apocalyptic Book of Enoch, and recently in Ewing’s SWORD, which (as wise and good-looking writers have pointed out) [Ed. Note: Rolling my eyes, here] echoes imagery from the Zohar (the defining texts of Kabbalah). So what does any of that have to do with Jack Kirby? Uh, nothing, I guess. But it still feels Jewish, I say!

CM: I mean, that’s why I’m glad you’re here to ask! One thing that strikes home here is the way Ewing writes Ben to be so immediately compassionate once dust has settled. The FF is not a set of characters that he plays with on a regular basis, but here in a guest spot he treats them with a care and a kindness that other writers should take note of when utilizing guest stars. They don’t feel out of character, they don’t feel out of place. They’re not shoehorned in just to drop a mean line of dialogue. They feel like they belong in this issue.

ZR: Oh, absolutely. Among many other things, this issue was a pretty great pitch for Ewing to be the next batter up for the Fantastic Four series, if there’s any justice in this fallen world. And boy does he grasp Ben Grimm instinctively – not just his New Yawk-by-way-of-Stan-Lee patois, but the whole ethos of his character. There’s a great moment, at the end of this scene, when Grimm calls Fixit the Hulk, and Joe tries to casually brush it off. But the Thing won’t have any of it: “That’s who you are, ain’t it,” he asks. At the beginning of this review, we talked about Charlene, and how her heroism wasn’t just in her actions, but in her steadfast commitment to preserving ownership over her name and identity. And so Grimm’s statement goes right to the crux of the matter: the Hulk has fought a lifelong battle to be the Hulk on his own terms, so damn it, take the name. Don’t let it be used as a weapon against him, or a way to cast aspersions on whether he has earned. It makes us remember again the refrain that goes back to Stan Lee, and rang out like a drum beat throughout this series: Hulk is Hulk. Damn right he is.

I also appreciate the neat bit of visual structuring that Bennett and Ewing pull off together here. During the fight between the Thing and the Hulk (and going back to the Leader’s assault on the Hulk over the past issues), there’s been a literal breakdown in the panels on each page, the borders growing more jagged and chaotic as the story grew more frantically unhinged. But as the Thing finally cools down, and the two characters settle into their meal and conversation, it stabilizes into a dependable, three-tiered panel grid. The universe is righting itself along with Banner’s mind, and all it took was a little bit of human kindness. And they said the other Hulk comic this month had the Christmas spirit.

Marvelous Musings

- Fantastic Four #5 is entitled, “Prisoners of Doctor Doom,” and features the titular mad scientist, in his first appearance, sending the FF on a wildly goofy time travel adventure to recover Blackbeard’s treasure, all of which leads me to the following question: men, what is stopping you from looking like this?

- Wait did you say there’s another Hulk book this week? Do we have to get back at it?

- Oh, for the love of…hey, can somebody get the emergency team on the line? We’ve got a situation here, and Christmas is involved. Zoe and Rob, ACTIVATE.