I revere Malcolm X. His autobiography changed my life. I emulate his pose and prose when I portend power projection – especially when I find myself in places where I’m assumed powerless. I don’t always succeed, but I always try.

Magneto represents unapologetic authenticity. He experienced the worst of man; he knows how sordid humans can treat those they’ve stripped all of humanity. He grew up in anger, and children are wont to become what they experienced in adolescence.

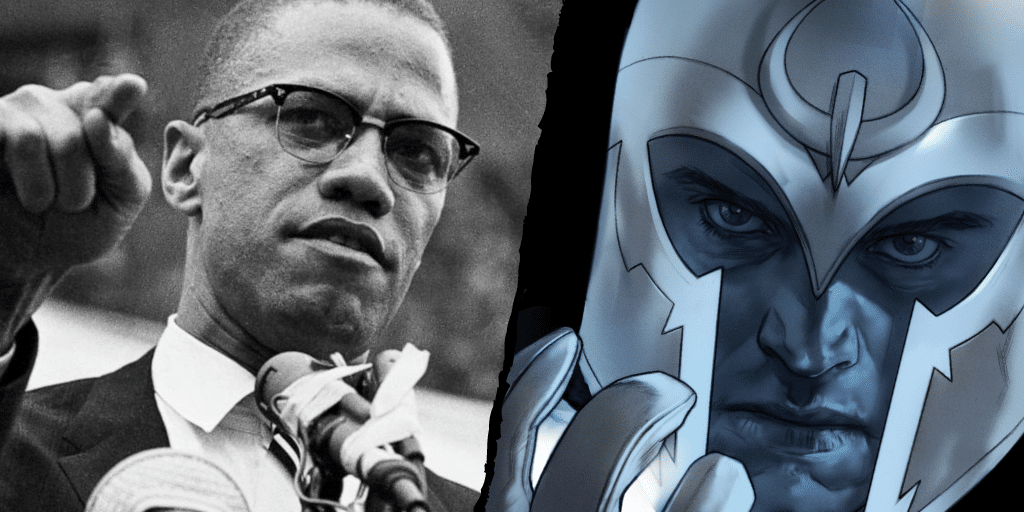

I’ve long been aware of Magneto’s comparisons to Malcolm, as these comparisons are extremely prevalent in mass media. I understand why. It’s deliciously tempting to draw a comparison between a fictional anti-hero and a man whose heroism was denied until death. A comparison may seem apt and appropriate; it may even seem complimentary. Yet as I appreciate them both, separately, I recoil violently at their comparison.

Others have written about how this analogy and it’s twin, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Professor X, are misguided (to be kind) and likely unintended. Of course analogies aren’t supposed to be perfect, but still, I found these analogies lacking. Magneto led a sect literally called “the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants”. If an analogy held, would I not be calling Muslims evil? Magneto killed, unrepentantly, torturing human and mutant alike. Malcolm was hard on fellow Black men, sure, but he never hurt the people he sought to save. Neither Malcolm X nor his acolytes were violent. (That self-protection equates to violence is a particularly telling equivocation.) The story of Malcolm is not one of violence, but of growth – from hustler to student to teacher to icon. His positions shifted as he learned more. He became a greater man as his understanding of the world grew. Magneto is an arrogant iconoclast. Growth is not one of his strong points.

Yet despite a clear preponderance of evidence, these analogies still persist. The people, it seems, want our heroes to have analogues. So maybe it’s time for better ones. Instead of Dr. King, why not compare Professor X to Booker T. Washington: a schoolmaster and statesman who used his prominence to advocate on behalf of his people; an advocacy which, critically, believed acceptance needed to be earned through actions to endear the oppressed to the oppressor. And Dr. King? Cyclops: the young leader, the eager student, the front line soldier, the face of the movement who, eventually, would become vilified and radical. But not wrong.

Magneto? Nat Turner. A witness to atrocities, he came into his power at a young age and used this power to organize and fight for freedom. He would be reviled in history books if he was even mentioned. But his actions, filtered through time, became precedent. Revolutionary. Right.

And what of Malcolm? Of my hero, my lodestar? To whom could I compare him? My mind filtered through names. I settled on Black Bolt, the monarch whose voice was a weapon. I began to type my rationale, but I stopped. It didn’t feel right. I realized I’m doing this all wrong. And doing this is wrong in itself.

I have not studied these men enough to state their political theory; to do so, even in jest, does a their legacy a disservice. I don’t have the range to have these conversations, and by making flippant comparisons, I am just as guilty as those who initially provoked my ire. And as I lack the range, so do too many others extend past their area of expertise to create comparisons, allusions and conversations they are ill-equipped to articulate or defend. People may mean well, but intentions, no matter how good, are no substitute for good information. Besides, we all know where good intentions lead.

Particularly for stories told about Black people by non-Black people, writers often shoe-horn subjects into stereotypical analogous aesthetics as opposed to embracing these Black subjects as multifaceted, complex and unique. These stories are told as a means to beatify Black people, actions, or movements. They are supposed to be complimentary. Yet these misguided attempts at inclusiveness too often falter. And when they falter, we are often gaslit to celebrate these attempts in the name of diversity.

This is not diversity. This is a disgrace. And partaking in exercises that strip complexity and nuance from historical figures for the sake of argument (or clicks) is unfortunate, even if you hold the subjects in high esteem. The problem is not simply one of inclusiveness (although having more faces writing and producing would help.) The lack of understanding around what one is analogizing, and the lack of development to the object of the analogy is the problem. Nuance is key.

I don’t always have the nuance to tell certain stories – even about fellow Black men. My experiences and privileges often blind me to what other people of other genders, ethnicities, backgrounds and orientations perceive. I’m sure I’ve made grand assumptions about others; and I’m sure if I was writing something on their behalf, I would run a high risk of getting it all wrong. I may have good intentions, but again, we all know where that road leads. But there is a road to a place of real inclusiveness, real diversity, and better, fuller, fleshed out comparisons, contrasts and stories. It just takes a little humility and a lot of work to get there.

The problem is not good intentions. The problem is not starting in an imperfect place, with imperfect comparisons. The problem isn’t even analogies; they are simply a storytelling tool. The problem is remaining unchallenged in ignorance and arrogance, as if imperfect attempts are sufficient so long as they are attempts. But sufficient is not sufficient. Especially when so much more is possible.

You’ve got to first recognize that you have a lot to learn. Then you must actually do the work of learning – and changing. And no matter who you are or what you’ve experienced you – we – have a lot to learn and change. You must change your perceptions and assumptions based on what you learn. This may mean re-writing the story you wanted to tell (as I re-wrote this essay). This may mean someone else needs to tell the story you want to tell. This may mean that story you wanted to tell doesn’t need to be told.

As a producer or consumer of art, I implore you to question everything you see: every allusion, every comparison, every conversation. To question if you know enough about enough to form an opinion. To take account of what you assume about even the most banal of things. I challenge you to learn whether those assumptions hold true and how, after doing the work, that truth serves you. I ask you to be fully aware how others perceive what you consume and what you create. To ask, to research, to question loudly, especially when and where your privilege empowers you.

I’m an artist. I’m sensitive about my shit. I get it. But if I don’t listen, I won’t learn. Moving forward may be uncomfortable, but no one and no thing has ever grown strong on comfort. Don’t let an imperfect starting point be where you finish.

Comics may be your escape. Comics are my escape, too. I know this feels like work, and it may feel paradoxical to ask people to work while passively enjoying an escape. But, when done right, a comic can be so much more. I, like you, value good art. You crave it. I am simply asking that you do the work to demand it. To create it. And to hold people accountable for not clearing the bar correctly. Even me.

Hold me accountable for uplifting the voices of other marginalized people. For not taking up space in conversations that don’t require my presence. For not assuming cursory knowledge of a person makes me an expert. For not making weak comparisons rooted in arrogance to prove my intellectual and moral superiority. And as we grow, past what we thought we knew to the honest, discomforting place of recognizing how much we don’t know, please do not chastise those who haven’t yet made the journey.

Don’t be in a hurry to condemn because he doesn’t do what you do or think as you think or as fast. There was a time when you didn’t know what you know today.

Malcom X

Malcolm X was my hero, but he would not be my hero if he stayed static. He learned. He humbled himself. He listened. He challenged himself. He grew. He brought millions on the journey with him. As he grew, so can you. So can I. Or, at the least, I can try.

A proud New Orleanian living in the District of Columbia, Jude Jones is a professional thinker, amateur photographer, burgeoning runner and lover of Black culture, love and life. Magneto and Cyclops (and Killmonger) were right. Learn more about Jude at SaintJudeJones.com.