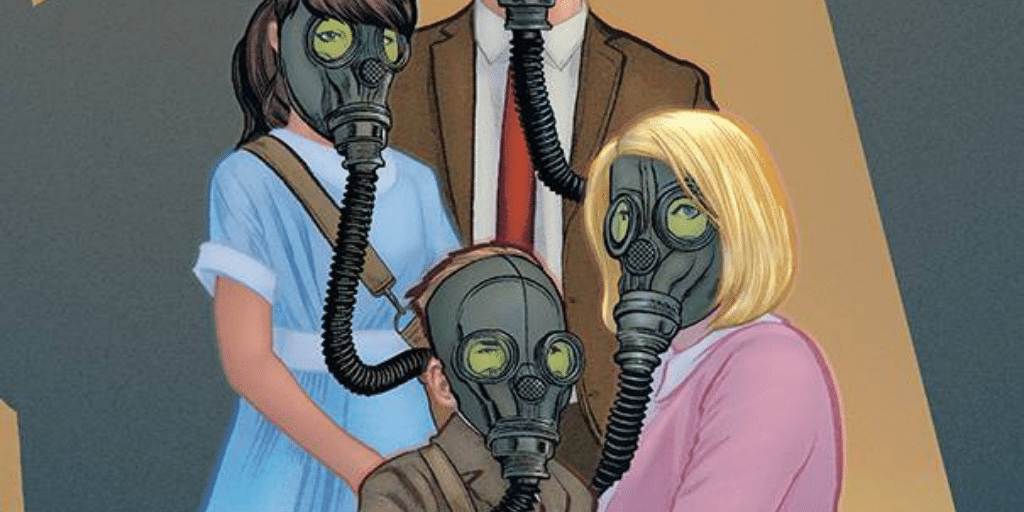

Where will you be when the bombs drop? And when you emerge from whatever shelter you were able to find, what will the world look like around you? Good luck … with whatever finds you. Nuclear Family #1/#2 by writer Stephanie Phillips, artist Tony Shasteen, colorist JD Mettler, letterer Troy Peteri and publisher AfterShock. Based on a short story by Phillip K. Dick.

Will Nevin: Forrest, my friend, my amigo, my Department of Truth compadre, as we get started on our second series, how are things? Are you enjoying the creature comforts of life, like power, clean water and a reliable source of food?

Forrest Hollingsworth: Will, I’m in the garage, and I’ve got a Dungeon Master’s Guide, I’ve got a 12-sided die, I’ve got Kitty Pryde and Nightcrawler, too, and — sorry, let’s get to the comics.

WN: I’ll be honest: I don’t think I’d last long in the apocalypse, primarily because — as The Day After so brilliantly illustrated in 1983 — there’s no fucking reason to keep going. Everything is dying or dead or on its way to being one of those two things, so why try? Aside from spite, of course. Jesus, most of what I do is because of spite. ANYWAY, Forrest, I think you alighted on this book a bit before I did — what spoke to you here?

FH: Oh we’re getting into the Forrest origin story right off the bat! I live in Washington State, and once, in passing, an elementary school teacher of mine mentioned the decommissioned nuclear facility, the Hanford Site, which houses over 60% of the United States’ high-level nuclear waste along the Columbia River — not all that far from where I lived. I was fascinated by it, by the equally terrible and industrious potential of it, the implication of an alternate history where something horrible or astounding happened there, and my fascination was only strengthened by nobody around me seeming to know about it or care (something that’s true even today, a handful of years after a leak there resulted in a $100 billion cleanup operation). Since then I’ve been pretty, admittedly weirdly, endeared to nuclear history and speculative fiction. Hell, I have a newsletter called ATOMIC CASKET that sees me mostly exploring decrepit nostalgia and the emotional and sociopolitical turmoil under the cover of Americana.

I think Nuclear Family, indebted to Phillip K. Dick’s short story “Breakfast at Twilight,” is particularly well positioned to explore those things I happen to already be fascinated with, and the combined effort of the first two issues left me feeling like the team here has a real eye for inventing and remixing well-trodden territory when needed.

WN: It’s an interesting trauma passed down by our grandparents, isn’t it?

As the Bombs Fall

WN: The first issue doesn’t necessarily get the premise out on the table — that doesn’t come until maybe three or four pages into the second — but it does lay out all the characters, and they seem to be special only in the fact that they’re not at all unordinary: Dad hawks used cars and tinkers with radios in the basement, Mom handles the domestic affairs, Sis has her teenage angst and smokes, and Little Brother is a scamp. What did you think of the characters before the book gets going?

FH: They didn’t call it Nuclear Family for nothing, did they? It’s very straightforward, but I did appreciate the character beats in the car sale scene. Tim is an honest man, uncomfortable with the idea of stolen valor even though he did actually serve in Korea. Military experience, a good heart and head on his shoulders, plus he’s kinda built? That’s the guy you want with you in a nuclear apocalypse, not that he knows that’s where we’re headed just yet.

WN: Overall, I think it’s a slow start, but I’m not sure how to fix it. I mean, I don’t think we can introduce the family, set the Cold War mood, drop the bombs *and* get to the real idea in this series in one issue — but at the same time, we’re also dealing with the tight confines of a miniseries. Maybe this should have been a double issue? An extra 10 story pages? I feel like I shouldn’t complain about any issue in which I get nuclear hellfire, and yet here I am griping.

FH: Yeah, I can grant you that. I am personally disturbed by the image of a kid playing out soldier fantasies with a military helmet and toy gun around the house (hilariously next to decor which reads “home sweet home”), but most aren’t, and without that there’s not really enough more explicit emotional beats or turmoil to foreshadow the unease that will soon settle in. Maybe a more intense fight with the daughter around the smokes, more annoyance about spending all the time in the basement with the radio, something would’ve helped stress the susceptibility of their home life to the external pressures of war, the Red Scare, etc.

What did you think of the faux Red Scare propaganda and infographics at the end? I thought they could’ve been better used or cut entirely, but maybe they help ground readers in the setting? Maybe they’re the extra pages you needed narratively?

WN: I am a fiend for backmatter, always have been. But your take on it makes me think the tone may have been a bit off — the pages were, after all, satirical, which doesn’t necessarily fit with the rest of the book. Feels almost like the team had an aesthetic they wanted to show off but the actual substance wasn’t important. I would have certainly preferred an essay on Cold War paranoia or something from an expert on Dick. *snicker* What would you have done with those pages?

FH: I prefer when backmatter tells us something about the characters as opposed to the setting, usually. Especially so when a lot of readers are probably already aware of this time period, its anxieties and even more narrowly its propaganda. Give me Dick and Tim’s service record or something.

WN: I like that idea. Their files would have given the team the same ability to flash the design skills while adding a bit more substance, absolutely. Before we get to the second issue, let’s talk about the art. I mentioned the hellfire — Tony Shasteen does a fantastic job with the action and the explosions, and colorist JD Mettler fuckin’ brings it.

FH: I particularly love how Rockwellian it is. Idealistic and straightforward, there’s a very specific evocation of utopia before everything turns that makes the impact that much more significant, like watching someone douse gasoline on a cherished family painting.

WN: Everything burns.

As the Smoke Clears

WN: As the second issue opens, we get into the real meat and hook (meat hook?) of the series. What did you think of the reveals (which I think we should endeavor to keep to ourselves until at least next time) as they unfold in #2?

FH: There’s a lot going on here in quick succession. I feel like we got just enough of Dan and Tim’s friendship in the first issue to make the tension here appropriately palpable, and the sharp contrast of the Rockwellian imagery in the first issue with the nuclear desolation here is exceptionally well executed. It’s mostly working for me!

I did want to call attention to one particular scene where, looking at a map, the cast discusses the destruction of “the West,” meaning plainly the geographical West of the United States. However, this is also a great cipher to discuss the ideological destruction of The West that a lot of Cold War/Red Scare propaganda was (and is) predicated on. The in-text war between the Communists and the Americans is more than material; it’s also sociopolitical, it’s immaterial and emotional. There’s a really good axis to have a lot of modern day discussions there, and certain (read: white supremacist) groups are equally invested in a fictional war on The West today. Adapting Dick doesn’t mean it’s just of its time, it is rife with parallels and implications that we culturally, politically, militaristically have not moved beyond. Does the actual war here justify the fear, the xenophobia, the assault on our neighbors? This is the kind of stuff I think a book like this can be very good at dissecting and discussing.

WN: It’s interesting that you tie the Soviets and the white supremacists/Birchers/QAnon/Trump supporters together as both looking to end the West’s post-World War II hegemony. So much of the last four years was a direct attack on what we thought were stable ideas — an internal conflict exacerbated in some instances by external forces like Russia’s involvement in both the 2016 election and the Brexit vote. Time, Forrest, is a flat circle.

FH: I meant that both the Red Scare and modern white supremacy were fixated on a cultural war that wasn’t … really happening? But you’re also right about the erosion of the West’s legitimate ideological grasp and its perpetrators — there’s a lot here! There’s even a 1987 song, Dominion/Mother Russia by English goth band The Sisters of Mercy that is about all of these same anxieties down to the Soviet occupation of the Middle East and puppeting of Western politics that Nuclear Family mentions in the first issue. At least it’s catchy.

WN: During the course of the second issue, we see a massive underground city that instantly made me think of Fallout — and there’s also “Breakfast at Twilight,” which I refuse to read or google lest I be spoiled — what’s some of the other DNA you’ve spotted so far?

FH: It’s good to know you haven’t read “Breakfast at Twilight”! I was curious how this might read to someone who doesn’t know where it’s headed (iteration and revision granted), and I’m kind of excited to see where our thoughts overlap and diverge because of it.

The city reminded me of Tokyo-3 in Evangelion, a heavily militarized bastion from the assault outside. There’s also elements of Roadside Picnic (The Zone), the Metro series and more here — the preoccupation with survival and utility above all else — and it’s obviously impossible to ignore McCarthyism’s ideological influence, which you can filter through literally hundreds of movies and novels of their time.

We really haven’t changed (and we probably won’t!), but that’s a good place for the book to begin its conversation, too.

Living in the Fallout

- The speech excerpted in #1 was a presidential address to Congress in which Dwight D. Eisenhower established the eponymous “Eisenhower Doctrine” regarding possible communist meddling in the Middle East. (That’s America’s part of the world to meddle with, you pinkos.)

- For more nuclear fiction set in the communist occupation of the Middle East, consider Metal Gear Solid V.

- In #1, it’s established by reference (the speech) and by title card that it’s 1957, but in #2, the family says it’s 1958. Were they in the basement for a year, or was that a continuity goof?

- There’s a largely held belief that the Cold War and its scaremongering was victimless. Julius and Ethel Rosenberg would disagree.