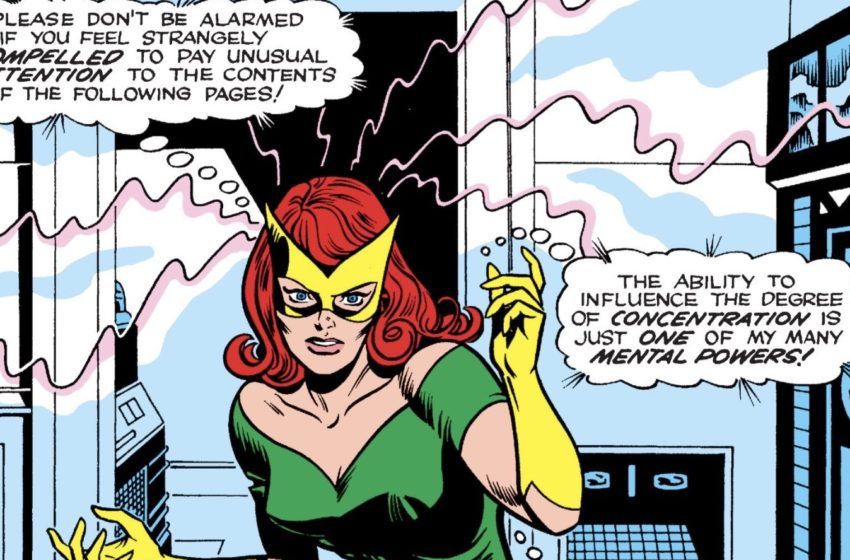

I’m sick of talking about Jean Grey’s green dress. You know the one—the minidress with the low-slung belt that debuted in 1967 and was abandoned in 1976 when Marvel Girl became Phoenix, before reappearing, along with the Marvel Girl codename, in 2019’s House of X/Powers of X and hanging around ever since. People love and hate the dress for a variety of personal and moral and political and narrative and aesthetic reasons. Even X-Men fans who don’t have an opinion on the dress itself often have an opinion on the discourse around the dress. Yet supposedly, everyone is sick of talking about the dress.

Or so everyone says, usually on Twitter, whenever the “dress discourse” starts up again. A couple of weeks ago, the inciting incident was writer Gerry Duggan re-tweeting something current X-books impresario Jonathan Hickman first tweeted two years ago: an image drawn by Phil Noto featuring Jean in her green dress overlaid with Krakoan text that translates to, “free thighs for a free people.”

If you’re completely unfamiliar with the dress discourse, an analogy might be helpful. Remember way back in February 2015, when everyone took to social media to argue about whether a dress was blue and black or white and gold? The discourse around Jean’s green dress is a little like that, in that everyone’s looking at the same thing, and seeing something different that they deeply believe to be true. Yet the arguments about Jean’s dress can’t be explained by different neurological perceptions of the color spectrum. Within a genre and wider culture with a very long history of treating women like shit, stories aren’t just stories, and neither are clothes. Clothes tell stories, and stories are part of how our culture creates and polices gender and sexuality.

Obviously, everyone’s entitled to like or dislike Jean’s green dress. But it’s a mark of entitlement to claim Jean’s dress is just a dress. (Or that Duggan or Hickman’s tweets are just tweets.) All superhero costumes and codenames are symbols, and Jean’s are no exception. Yet Jean’s costumes, and our reactions to those costumes, are also bound up in our individual and cultural understandings of female power—and what it should look like. That’s why it’s important to talk about Jean’s green dress, even when we’re sick of talking about it—maybe because we’re sick of talking about it.

Even in the 1960s, Jean’s dress was complicated. In the US, UK, and much of Europe, miniskirts and dresses were staples of the 60s sexual revolution. Minis advertised female empowerment, particularly those of the “mod” variety, which were often associated with adventure in brave new worlds, as in Pierre Cardin’s 1964 “Space Age” collection. Yet when worn by, say, the uniformly gorgeous and usually speechless secretaries in The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (1964-68), minis also advertised a particular form of empowerment, connected to youth and sexual availability (specifically, heterosexual availability). In this, they resonated with Helen Gurley Brown’s version of “girlish” feminism, which she first articulated in her 1962 bestseller Sex and the Single Girl then wove into her wildly successful revamp of Cosmopolitan magazine, where she served as editor-in-chief for 32 years, from 1965 to 1997.

As Hilary Radner discusses in her book Swinging Single: Representing Sexuality in the 1960s, Brown advocated for the sexual rights and appetites of women and urged them to assert independence by working outside the home. Yet she also counselled women to safeguard their independence by maintaining sexual availability throughout their life, which they should communicate through the perpetual presentation of girlish-ness (or, perpetual immaturity). Writes Radner: “Though [Brown’s] Single Girl is a consumer, she is a smart consumer… Her girlish sexuality is her small capital, a capital to which every woman has access and that Brown encourages every woman to exploit.” Rather than criticizing men or patriarchal culture, Brown “advocates a pragmatic approach in which men constitute neither allies nor enemies, but a series of opportunities and obstacles that a woman encounters in her attempts to achieve economic stability.”

The tensions bound up in miniskirts and dresses evoke the same tensions bound up in Brown’s girlish feminism, which are in turn the same tensions bound up in early second-wave feminism and the sexual revolution as most girls and women experienced it, which is to say incompletely. In the 60s, the agency conferred by a miniskirt or dress was always tentative and unstable, dependent on the wearer successfully navigating the approval of the male gaze. The same is true for Jean. In X-Men #39 (1967), Jean chooses the green dress. Following in the footsteps of Sue Storm and Janet Van Dyne, she even designs it, along with new costumes for her male teammates.

And yet, the costumes are Professor X’s idea. When they’re revealed, he declares, “The X-Men are scarcely children anymore!… It’s time they looked like individuals—not products of an assembly line!” While all the costumes are linked to maturity and individuality, it’s notable that the male characters graduate from undifferentiated training uniforms into traditional supersuits whereas Jean graduates into girlishness, effectively donning clubwear with a mask. Jean’s very clear difference from her male teammates recalls her introduction in X-Men #1 (1963), which similarly makes a spectacle of her gender; in that issue, the male X-Men actually fight among themselves for the opportunity to ogle her. Yet there, Jean donning the same uniform as her male teammates is at least a disruptive anomaly; Jean infiltrates male space, and the sexiness of the training uniform on her body suggests all supersuits might be sexy, depending on who’s looking and how. But in X-Men #39, Jean becomes more purely girlish, and must, like the real-life women inspired by Helen Gurley Brown, negotiate her access to power within that context.

Once again, because I can’t emphasize this enough: I’m saying minis are complicated, not evil; I wear plenty of miniskirts and dresses, and don’t think it makes me a bad feminist or a dupe of consumer culture. It’s also not the fact Jean’s dress is sexy that’s an issue (at least for me). It’s the specific ways it’s sexy on this specific character with her specific history. According to comics scholar Peter Coogan, the most effective superhero costumes communicate a character’s mission, powers, and identity, expressing their “inner character” and embodying their biography.

Batman exemplifies this convention; he’s inspired by fear of bats to inspire fear in criminals by dressing up as a bat. The X-Men’s costumes don’t reflect the convention as clearly, partly due to the team aspect (they use a group symbol rather than individual ones), and because the often-unique bodies of mutant superheroes serve their own identifying function. Yet in the X-Men comics of the 60s, Marvel Girl’s costume does, for better or worse, compliment her power set and role within the narrative. In her book The Great Women Superheroes cartoonist and comics historian Trina Robbins observes that virtually all of Marvel’s female superheroes of the 60s are given “hands off” powers—like telepathy, telekinesis, invisibility, force-fields, or magical hexes—that let them to contribute to the fight by doing little more than strike attractive poses at the edge of the fray, often gesturing toward the action with a single upraised hand (until they pass out from the strain, something that happened frequently to Marvel Girl). This allows stories to sidestep the impracticality of Jean’s costume; a minidress is sensible so long as you don’t actually need to run, jump, or kick.

Yes, many superheroes have visible underwear, or at least skin-tight costumes that openly invite eroticism. Yet Jean doesn’t wear her underwear over her tights, like most male superheroes do. Nor does she wear a corset-style bathing suit over stockings, as many other female superheroes of the 60s did. Because Jean’s 60s dress always hides her underwear, we know there’s something to hide. The idea of peeking under Jean’s skirt suggests more taboo intimacies and realer erotic possibilities, for any of the presumed male audience that was encouraged to objectify her, or readers of any gender who might have identified with her; in this, the green dress evokes competing expectations, teasing both exposure and agency without making good on either. The constant threat of exposure also communicates constant vulnerability; Jean can’t participate in the fantasy of impenetrability communicated by the condom-like sheaths worn by her male teammates. Nor do her powers visually armor her, the way Bobby’s snow/ice layer does.

In contrast, Jean’s next costume—the green-and-gold Phoenix costume that debuts in X-Men #101 (1976)—strongly communicates individual identity within an era of second-wave feminism that had moved past accommodation in pursuit of transformation. The cover of X-Men #101, featuring Jean as Phoenix rocketing skyward as her teammates flounder in the water beneath her, hints at Jean’s later villainy, yet also foregrounds a shocking break from the more submissive woman (or girl) Jean had been.

The Phoenix costume and codename embody this change, and not just because the costume features full-coverage tights. The Phoenix costume and codename are imbued with Jean’s mission, powers, and identity—and thus, her agency—in ways the Marvel Girl costume and codename never were; this costume that Jean creates spontaneously using her newfound ability her rearrange molecules symbolizes a fundamental re-making that is, at least initially (before various revelations and retcons involving the Phoenix Force), self-directed without being selfish; Jean remakes herself to save her friends who regularly save the world, symbolically supporting the proposition that second-wave feminism’s efforts to remake gender roles are a similarly world-saving endeavor.

I remain deeply affected by the way Dave Cockrum and Danny Crespi render Jean’s body on the cover of X-Men #101, her fiery red hair billowing wildly amid a cross of flame as her golden-gloved fists clench at the end of slim yet powerfully flexed arms, her mouth agape in an exultant scream. I’ve felt this fury before, and would dearly love to feel this release. The rendering of Jean’s lower body also matters. Her thighs are pressed tight, yet her crotch is darkly shaded; it is, in other words, visible in a way it wasn’t before, when the minidress teased yet modulated Jean’s sexuality.

Though Jean, as Phoenix, remains ideally attractive and frequently objectified, a quest for agency is central to Jean’s character journey over the next several dozen issues, as she transitions from Phoenix to Dark Phoenix and back, briefly, to Marvel Girl. It’s as Phoenix that Jean finally consummates her relationship with Scott, and she does so with direct, shameless intent, using her new power to perfect their pleasure; on a clifftop with Scott in X-Men #132 (1980), Jean removes Scott’s visor before topping him, her power such that she can modulate his, for both their sakes. Jean’s passion as Phoenix is linked to both love and death; in an interview in the first X-Men Companion, Claremont likens Jean’s genocidal consumption of a planet to “the quest for the cosmic orgasm.”

But despite indulging in misogynist tropes about the consumptive threat of female sexuality, the Dark Phoenix Saga also shows Jean actively fighting for personal and sexual agency against both the corrupting influence of the Phoenix Force and the expectations of controlling men, including all of Mastermind, Professor X, and Scott. Where Jean’s time as Marvel Girl was all about managing competing expectations, Jean’s time as Phoenix is an exercise in consciousness-raising.

The importance of the Phoenix costume and codename becomes even clearer when Jean reverts to Marvel Girl before the final battle against the Shi’ar Imperial Guard at the conclusion of the Dark Phoenix Saga. In Uncanny X-Men #137 (1980), Jean as Marvel Girl is introduced entering the room through a dark doorway, mincing into the light as Scott, positioned in the foreground, gawks at her, and invites us to do the same. When Scott asks Jean why she’s chosen that costume for the battle, she says: “I’m not sure—nostalgia? Pride? I started as Marvel Girl, and that’s how I’ll finish.” In other words, Jean doesn’t know why she’s wearing the green dress; she only knows she wants to die in it.

There is agency present here; that shouldn’t be overlooked. Yet the return of the dress also signals a return to sexual innocence and purity, as well as submissive heterosexual monogamy; the woman who topped Scott and experienced cosmic orgasms is gone, replaced with a woman who holds Scott’s hand to run behind him, then dies, primarily, to save him, screaming his name as she destroys herself. Jean’s return to sexual purity is further emphasized in the Dark Phoenix retcon in 1986, which asserts Jean was never in control of her actions as Phoenix and gifts her a new body safely cocooned, like Sleeping Beauty, at the bottom of Jamaica Bay. In this retcon, Jean is symbolically and literally re-virginized. Though she doesn’t don the green dress, she does resume being called Marvel Girl.

Since her second rebirth, Jean has charted a winding path through many different versions of empowerment; along the way, there have been many more costumes, signalling other feminist moments, concerns, and contradictions. But she’s never, outside of AUs, flashbacks, and dreams, gone back to the green dress. So—why now? I don’t think the current X-Men creators consciously want to regress Jean. But I can’t be sure. She’s never discussed going back to her original costume or codename or addressed it in a thought bubble; we’ve never seen her alone in her room, contemplating what to wear; we don’t know how she feels about any of these things, or if she has a better answer to the question of why she’s wearing the dress than the one she gave Scott back in 1980.

To date, the only attempts at explaining Jean’s reversion to her old costume and codename have occurred off-panel. In an X-Men Monday interview from October 2019, Hickman advises fans to consult “the most famous time she put this costume back on.” Presumably, Hickman means the conclusion of the Dark Phoenix Saga. But he doesn’t elaborate, or address the fact that within that moment, Jean couldn’t explain her choice. In another X-Men Monday interview from several weeks ago, Senior Editor Jordan D. White similarly cites the Dark Phoenix Saga reversion, and adds, “the reason she’s called Marvel Girl is because Jean doesn’t have a lot of great codenames,” and because “Marvel Woman just doesn’t sound good.” These aren’t exactly inspiring reasons for Jean to revert to a potentially infantilizing identity.

My most charitable reading is that Jean reviving her original costume and codename signals she’s no longer afraid of corruption; she’s reverting to girlish purity, but also choosing it. That matters, because it’s a knowing innocence, one forged in blood and knowledge—including knowledge of death and resurrection, something Jean knows more intimately than anyone. This version of Jean isn’t afraid of dying or being corrupted; maybe she’s even immune to history. She’s also unafraid of sex or pleasure, as evidenced by her polyamorous relationship with Scott and Logan. Yet it’s worth mentioning that this character development happens, once again, off-panel, revealed in a data page that maps the characters’ adjoining rooms.

I have nothing but love for anyone who finds empowerment in Jean’s decision to re-become Marvel Girl. But I’m personally too mired in the history of that name and dress and others like it, and the ways that history is written into my own relationship with my body and my body’s relationship with the world. Though I wear fewer minis in my 30s than I did in my 20s, when I did wear them a lot, I loved them dearly, drawing style inspiration from 60s icons like Edie Sedgwick and Emma Peel. Yet from wearing minis, I know they present certain challenges. When wearing a mini, you have to sit and move in certain ways to avoid becoming the wrong type of spectacle. You need to adjust your clothes before sitting and keep your thighs pressed tight when doing so. And there are certain things I never do in a mini, like run, jump, or crouch. Instead I walk or amble, and if I’m in a dark club, I might dance a little. But if I drop a pen or bookmark on a subway platform while wearing a mini, I perform an awkward closed-leg shimmy to pick it up without showing my ass, because being exposed there, in that way, would threaten my ability to control the sexual power a mini ostensibly confers.

I guess the fact Jean doesn’t worry about these things should feel powerful; I should embrace her ability to wear a minidress to perform black ops missions in the jungle as yet another of the many magical things she can do that I can’t. And part of me does love the illogic of it all, the same way I love so many other excesses of superhero comics, like giant heads designed only for killing, and Gorilla Cities, and scientists who transform into pterodactyls wearing short-shorts. But on the page, to my eyes, the way Jean moves in her green dress doesn’t communicate fabulous excess; she seems, instead, hampered and tonally strange in ways that often take me out of the story.

There are basically two options for when Jean flies in the dress (an ability she didn’t have when she first wore this costume). She either presses her thighs together—firmly or coquettishly—or else raises a knee to block our view of her blacked-out crotch. Often, the dress defies wind and gravity, hanging limply and making convenient folds when it should be flapping wildly. Of course, many superpowers defy gravity. But if Jean is using her telekinetic powers to keep her skirt at bay, couldn’t that energy be better used elsewhere? When Jean walks or runs—on air or on the ground—the skirt frequently flutters around her upper thighs, perpetually teasing that taboo exposure. I find these images the most uncomfortable. Certainly, there are superheroes for whom it would be totally in-character to want to look flirty-cute while stepping over dead bodies. But I’m not convinced Jean is one of them. Of course, artists could treat the dress like a real dress, constantly exposing Jean’s underwear. This wouldn’t necessarily be better, but at least it would be honest, and might finally move us past the historical obsession with Jean’s purity.

Am I taking a fictional dress worn by a fictional woman in a superhero comic book entirely too seriously? Undoubtedly. But I don’t feel I have a choice. I wish I didn’t feel uncomfortable watching Jean move in that dress, then more uncomfortable every time I’m told by another fan or critic or one of the architects of Jean’s official adventures that I’d be liberated if I could just stop worrying and love the dress. But I can’t. Instead, I keep thinking: if whoever decided to resurrect the dress didn’t know it would be controversial, they’re ignorant of complaints feminist fans have been making for decades. If they did know it would be controversial, they’ve shown a dispiriting lack of empathy for the fans who’ve made those complaints and continue to make them, who are largely though not exclusively female.

If Jean’s bare thighs and girlish minidress signal freedom—freedom for whom? To do what? None of Krakoa’s male superheroes wear minidresses, and Colossus is the only male mutant on the island with a costume that exposes his thighs (which are, unlike Jean’s, typically armored rather than bare). Bare thighs are Jean’s right, but maybe they’re also her responsibility, much like they were Wonder Woman’s responsibility so many years ago, when her creator, William Moulton Marston, imagined her as “a feminine character with all the strength of a Superman plus all the allure of a good and beautiful woman.”

Maybe I could forget my complicated feelings about Jean’s green dress if I had a Krakoa to go to. A magical island free of all our bigoted, prudish human rules and restrictions, where sexism doesn’t exist, and neither does #Comicsgate, or up-skirt photos, or federal judges who blame rape on women failing to keep their thighs shut, and where what power looks like in superhero comics isn’t still the primary purview of men who are very good at telling us female characters have agency but less good at showing it.

But that Krakoa doesn’t exist. Not in real life. Or in comics.

I’m still sick of talking about Jean’s green dress. But I’m sicker of explaining why we have to.

Anna Peppard

Anna is a Ph.D.-haver who writes and talks a lot about representations of gender and sexuality in pop culture, for academic books and journals and places like Shelfdust, The Middle Spaces and The Walrus. She’s the editor of the award-winning anthology Supersex: Sexuality, Fantasy, and the Superhero and co-hosted the podcasts Three Panel Contrast and Oh Gosh, Oh Golly, Oh Wow! Follow her @annapeppard.bsky.social.