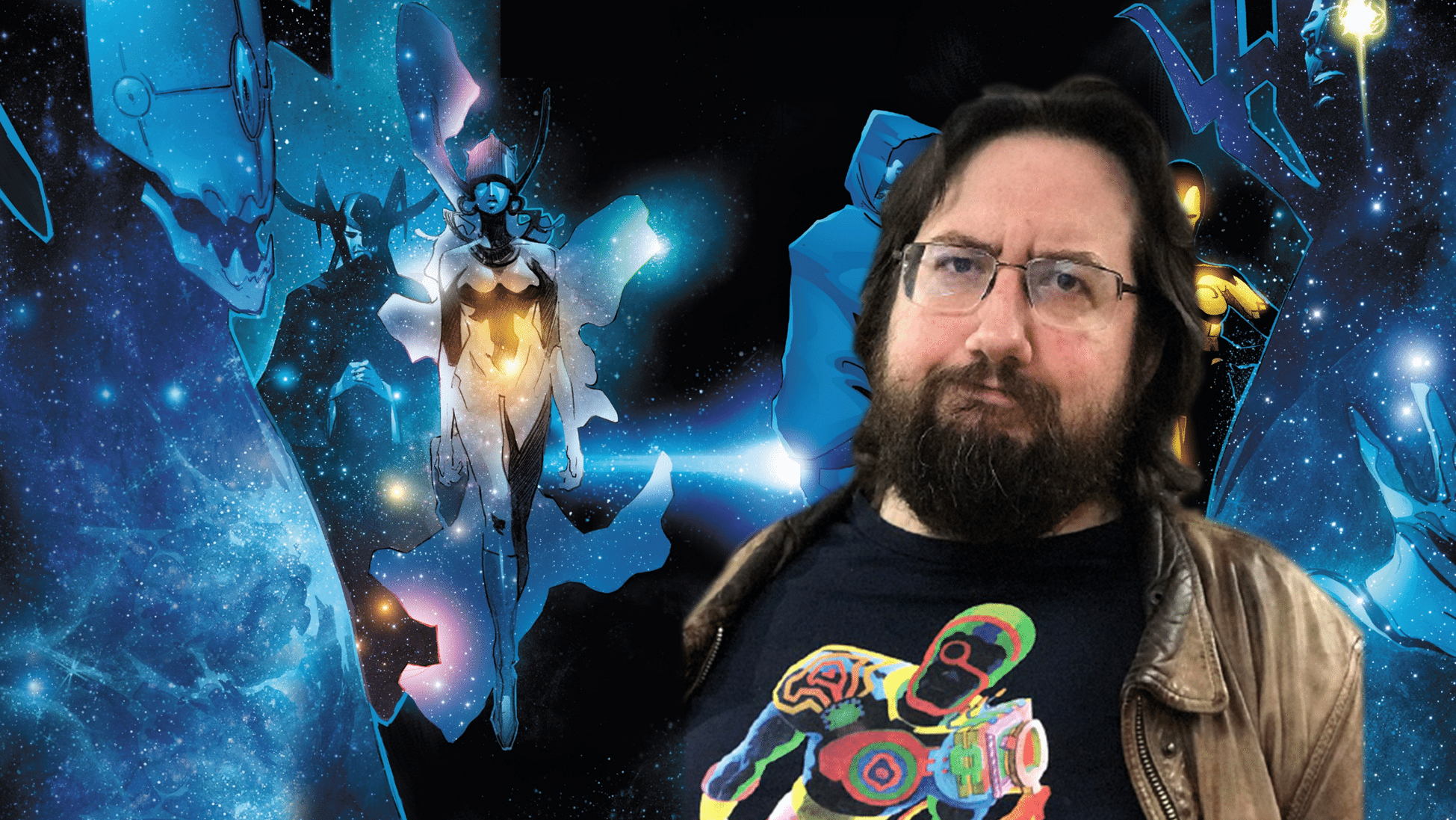

Since getting his start as a writer at Marvel in 2013, Al Ewing has become one of the publisher’s resident experts in cosmic concepts and big ideas. From The Ultimates and Contest of Champions to his recent and upcoming runs on S.W.O.R.D., Guardians of the Galaxy, Defenders and Venom, Ewing has always shown a willingness to play around with the biggest characters and wildest ideas in the company’s toy chest. We recently sat down with Ewing for a freewheeling conversation about space, cosmology, the X-Slack, and everything in between.

I’m a Proponent of Synchronicity

Al Ewing

Zach Rabiroff: Over the past few years, you’ve worked pretty extensively on the cosmic end of the Marvel Universe. “Cosmic” is a broad term that I think means a lot different things to a lot of different people. So let me start with a broad question: what does “cosmic” mean to Al Ewing?

Al Ewing: I’m glad you asked that, because “cosmic” is so broad, the way that people approach it, that it becomes almost meaningless. Like, just off the top of my head, Englehart doing the Molecule Man and the Beyonder…Secret Wars III, I think. It’s been so long since I read it, I can’t remember any details. But it had, like, you know, the Beyonder in it, it had the Molecule Man in it, it had Kubic in it…it had all the big people. And, you know, as long as the “big idea” people are there, that’s cosmic. But, you know, Dan Abnett and Andy Lanning doing a story about Ronan getting revenge on some Kree political house, which I think was a part of the original Annihilation [Ed. note: It was actually written by Simon Furman, but don’t tell Al that], that’s cosmic as well. So it’s like, okay: the Super Skrull is cosmic, and Eternity is cosmic, so at what point do you kind of lose what cosmic is? So I tend to think of cosmic as the Starlin stuff. The big people. Cosmic is Thanos when he’s off in the white void talking to Eternity and Infinity and Order and Chaos and all these people. When Thanos is just murdering people on a space station, that I would class as “Marvel space.”

Rabiroff: So it’s really the type of story, the genre, more than the set of characters that you’re dealing with…

Ewing: It’s tricky, because at a certain point it does come down to drawing the lines. Like, Galactus…if he’s having a chat with Eternity it’s Marvel Cosmic. Or if you look at him from the human point of view, it’s Marvel Space. And I can see how it all connects, and I can see how people would want it all to be one thing. But from a writing perspective, it’s just impossible. It’s such a broad church that I prefer to break it down a little.

Rabiroff: So does that become a challenge to you at all, in terms of what kinds of stories can interact with each other? Because when we’re talking about something that’s supposed to be one universe after all…

Ewing: You know, one type of story will turn into another type of story. But it’s like, with something like Guardians [of the Galaxy], I thought I was going to have some fun with the Master of the Sun. But I didn’t go into it thinking, “okay, this is going to be one of the books where I get to do fun stuff with Eternity and Order and Chaos and all of the big Starlin people, or make up my own big Starlin people)– which is much more what Defenders is. And we can go to those places if we like, if the story takes us there. I definitely don’t treat the original Master of the Sun as an actual guy, I treat him as a sort of personification in the Starlin mode, so he’s always sort of off to the side in memories or in dreams, and not really being part of things.

But 99% of my Guardians run takes place in space: places you can go if you have a spaceship. I feel like if you’re chatting with Eternity, that takes more than a spaceship. You need Quantum Bands or something. Space is a place. Cosmic is a state of being.

Rabiroff: That sort of brings up a related question, which is that in a number of the cosmic works that you’ve done, there has been a kind of systematizing of Marvel’s cosmic universe — you know, naming the galaxy that the Skrulls are in, or numbering the previous cosmos. So how do you find the line between categorizing Marvel’s cosmologies, and holding onto something kind of big and ineffable?

Ewing: I’m a proponent of synchronicity and serendipity. I feel like happy accidents in writing — as opposed to just horrible shit hitting the fan — but happy accidents are a thing to be treasured. So the galaxy…I’ll talk about the galaxy quickly. And I say “galaxy,” singular, because galaxies are absolutely fucking massive! And the space between them is even bigger. And when you actually sit down and figure out, okay, the Skrulls are impinging on the Kree’s boundaries…that’s a great politics plotline, but that’s like saying I have an issue over a garden fence with a guy in Azerbaijan.

Rabiroff: Right, it’s like when you’re playing risk and North Africa invades Brazil.

Ewing: So, I have never played Risk. A horrible thing for me to admit. I do have an intact copy of Risk Legacy that at some point I will get time to play.

But no: I cheated. I said, “well, they’re the Guardians of the Galaxy. There’s one galaxy.” I don’t care what anybody said before, I don’t care what anybody says after: for the purposes of this book, there’s one galaxy, and if people complain, we’ll shrug and say, “well, there’s always been one galaxy. You must have imagined all those other stories.” But, yeah, no: it’s cheating. I feel like at this point, I’m allowed to completely ignore continuity. I have paid homage to it enough. I am allowed to completely ignore it to make my life easier.

Rabiroff: So what is your attitude to continuity, because that in itself is kind of a fraught term among comic creators, at least since the ‘90s.

Ewing: Either continuity makes the story better, or makes the story worse. And if it makes the story worse, even by a fraction of a degree, you really don’t need to bring it up. And sometimes that line can be really hard to see, because there’s an element of the continuity nerd in me, where I’ll do some research to make sure I’m not contradicting anything. There was one thing where I think I wrote that Moondragon had never cried, and I was like, “I better look up all previous instances of this for Moondragon.” And nope! There she is, shedding a tear on page four. And it was a good line, so I had to sort of rejigger it.

Rabiroff: But you did, when possible, want to hold onto the official character history?

Ewing: Yeah, when possible. I don’t ignore this stuff, and I don’t…very occasionally, if something just does not fly, then I will just quietly excise it or ignore it.

Rabiroff: The location of the galactic empires is one thing, but can you think of another instance where you’ve just had to jettison continuity because it didn’t work?

Ewing: One example — I never mention the magic sword that allegedly shrank Puck from a strapping six-foot man, because I feel like it lessens the character somewhat if a condition that lots of real-world people have is some magical curse in his case. In my head, the magic sword just made him very long-lived.

At the same time sometimes you’re dealing with characters who have done unpleasant things, and there’s an argument that once something is on the page, it’s set in stone. And are we then, as authors, sort of making excuses for the characters if we erase what they did? Are we sometimes covering up fictional crimes? And you’d be right. You could say that. So I don’t know.

Rabiroff: And I guess the other option is to go back and deliberately refashion something that’s happened in the past into something more pleasant.

Ewing: Right, and I guess the equivalent with the galactic map would be to do a big story where all the galaxies mash into one, like in Crisis on Infinite Earths. And that would be terrible! Nobody would want to read that! But in the main, I try to treat everything that’s come before as 100% true. If it was on the page, it happened. Ninety-nine percent of the time I do that.

Rabiroff: And the Master of the Sun story is really an example of that, because as far as anybody was concerned, that was a story that did not seem to be in contemporary continuity — it seemed to take place off to the side, in that original Steve Englehart story, and then was never mentioned again. So what made you want to bring that back and incorporate it into the mainline Marvel Universe?

Ewing: I’d heard about Steve Englehart’s original plan, to have Star Lord go through the planets of the solar system, and go through the astrological houses. And that seemed really interesting. And he’d sort of become this slightly goofy [character]…very much his movie persona. And I don’t know the timeline [with regard to the first Guardians movie] of when people decided what they wanted Star Lord’s character to be, so I don’t know if it was a desire to make his character a little more likeable, or more ready for the big screen.

But I thought I’d like to bring a little bit of that cosmic mystery back to the character, and I thought: my end goal was to make him the new Master of the Sun — a literal Star Lord — and we’ll get some of the cosmic stuff back to him. And I thought, what if we could do our version of the whole Steve Englehart plan in one issue? So he comes back as this very changed, very grown character. So it was all trying to restore some the vibe of that very first issue.

Because in that first one, I seem to remember that he was really terrible. I mean, A) he’s not in the Marvel Universe, he’s in some future. B) He’s not a really nice guy — he’s a terrible human. And C) he’s offered the chance for revenge, and he takes it and massacres everyone who murdered his mother, or at least in his head he did. [Ed. Note: It’s a weird story.] So it’s trippy in a whole bunch of ways. And I thought it would be fun to put the Massacre of the Sun back in his origin, and keep all of the new origin — because I didn’t want to do yet another origin — and add a little of that magic back to the character and see if it would stick.

I Love the Operatic Stuff

Al Ewing

Rabiroff: Had you been deeply familiar with a lot of these cosmic stories before you started your run?

Ewing: A lot of it is osmosis. A lot of it is kind of picked up piecemeal. Because if you’re talking about the history of the Kree, or any of these space people, unless you were buying all of the Marvel comics, it’s really hard to follow it all. So I’m getting most of my stuff from these old Essential trades, these big, fun books of stuff. And now we have Marvel Unlimited, so I can go on there and look through everything.

But I’m influenced by Kirby in a number of ways — almost more the New Gods stuff, but obviously the Galactus trilogy is just huge. I feel like around there, around issue #50-60 [of Fantastic Four], that’s where the Lee/Kirby machine is running at its peak, and it’s Kirby providing a lot of the energy for that. And I feel like I read somewhere that they had a falling out…

Rabiroff: I’ll say…

Ewing: [Laughs] One of many. Around the first Adam Warlock story…

Rabiroff: The famously changed first Adam Warlock story.

Ewing: Yeah, because Kirby wanted to tell one type of story, Stan Lee wanted to tell another type of story, and Stan Lee was the guy who wrote the words. But that’s a huge influence, all the Kirby stuff. Right up to that Galactus special where they make the change from the Thor origin where he’s just a guy from this one planet, to where it’s like, no, actually, he’s from a previous universe. And that’s massive.

The Adam Warlock stuff, especially Starlin’s, although I did read a bunch of the old Jesus stuff…

Rabiroff: Ah, yes, the cosmic Jesus on Counter-Earth.

Ewing: It’s so blatant! There’s literally a “you will be my rock, Peter,” except he’s talking to a tree man: “You will be my…tree.” And it’s like, “for God’s sake…”

Rabiroff: You know what it is, I think? Jesus Christ: Superstar had just come out on Broadway when that series debuted, and that was Marvel’s version of cashing in on the Jesus craze.

Ewing: It’s shockingly blatant. But then you get the Starlin stuff, which is fantastic in a whole different way. You get these mind-ballads that are just, like, 200 panel pages with these different cosmic ideas on them. So I love that. I feel like a lot of what I do is trying to recreate the energy of the ‘70’s at Marvel, where you’ve got a bunch of people who are exploring their own private trip and writing their own stuff out on the page, with the necessity of telling superhero stories almost as a secondary thing. I feel like most of what I’ve done for Marvel has been at least attempting to follow in that tradition. Because if you’re writing about something, and it’s not personal to you, then I don’t really know how to make it interesting. If it was just, “what if this action figure fought this action figure.” The place where I’m weakest is always the fights.

Rabiroff: Does that feel constraining at all, to fit these stories into that superhero structure where it needs to climax in a fight scene?

Ewing: No, because I love the operatic stuff, and I like the declamatory nature of it. I’m also a big fan of the non-fight fight, where it’s some emotional breakthrough that’s made. Which, getting back to Guardians, a lot of people feel like that last issue was a little bit rushed. And…yeah. We had a certain amount to fit in a certain amount of pages, and I take the blame for that. But you did get a big emotional catharsis! Which is almost as good as a fight.

Rabiroff: Did the end of that run go according to plan, or were things changed that caused you to restructure it?

Ewing: I knew for a while that #18 was going to be the last issue. I guess I was hoping I could get 30 pages, but I knew I didn’t have those 30 pages. But I knew I needed to have Doom do the big, magic spell absorbing Dormamu’s energy thing, and I knew I needed to have that be the big, exciting thing. And since this was the last issue, I wanted to spend 2 or 3 pages on a celebration. So there was a lot of stuff, and, I don’t know, if I had it all to do again, maybe I’d skip the Hellfire Gala. But that conversation between Nova and Magneto — I really enjoyed having them meet, and everybody loved that. But if I had it all to do again, maybe I’d rethink whether to tie-in so directly.

But I have one of these what-if’s for every book ever. Basically what I got was almost a blank check. The note from above was, like, “you’ve done 12 issues of this interesting thing, how do you feel about 6 issues of a big-ass action movie?” Because basically where we were coming from was a place of, we want people to buy the book. So there were these considerations, but…I feel like the choices made on those last 6 issues were good choices. But when issue #18 rolled around, I knew there wasn’t going to be an issue #19, and I chose to favor the emotional core over the mega-space-battle.

Rabiroff: So, process-wise, how far in advance do you plot your stories?

Ewing: I never…well, that makes it sound like I’m plotting everything on the fly, which isn’t true. But at the same time, if I get to a place where it’s like, “this might work, this is a good idea,” then I’ve got mileage out of just doing that. But usually I have, like, an idea of an ending — an idea of big scenes I want to get to. Like, I knew how Guardians #12 was going to go, and S.W.O.R.D. #6 I had planned for ages and ages: I wrote that months ahead. Especially that Magneto bit at the end. That was pitched, and I actually wrote that very early, because I wanted to be like, “…and it will look like this [gestures in imitation of Magneto]” to the rest of the room.

Rabiroff: So, let’s talk about S.W.O.R.D. a little, because obviously there’s been a lot of big news coming out of the X-Men office lately, but I imagine the process of writing that book, editorially and in the X-Slack, looks very different from some of the other books you’ve worked on.

Ewing: I’m sure you’ve heard all the tales of the X-Slack by now, but it’s such a good way to work. It’s a trip. It’s like a writers room that just doesn’t stop. So that’s great: we can just dive in at any point and run stuff past one another, and that’s a great way to work. There’s more of a sense of immediacy in a Slack environment.

Originally, S.W.O.R.D. was pitched as issue #1-6: I had an idea of what those would be. Mutant space program was kind of my original pitch. And then the idea was that it would be a sort of link to the outside world, and it would be a place where we could get involved in all of these space happenings. It was almost like S.W.O.R.D. #6 was built before issue #1 was. Because issue #6, I knew we were going to Mars — we were talking about that months before anybody even guessed we were.

Rabiroff: Almost anybody…

Ewing: Originally, I pitched something for issue #1 that was more like issue #5, in that Brand was going to be basically taking care of the space program. But that wasn’t really a sort of issue #1 plot, and at some point I had this idea I pitched to one of the Zoom meetings that I thought would be fun: “what if we had this mutant space currency. And they can make it out of this magic metal, like Adamantium, and Vibranium, and then we’ll have a third one.”

But the currency was the bit I pitched, because I knew Jonathan [Hickman] would love that. And he gave me a bunch of notes that were great, one of which was, “have a real bad guy on there.” And it was like, “okay, who are the bad guys who haven’t been taken? Oh, here’s Fabian Cortez, wonderful, he’s Patrick Bateman! He’s awful! That’s great, let’s bring him in!” So then I did issue #5, and it’s like, well, there’s another part to his story, and I’m not going to be able to get it immediately. And then Si [Spurrier] was like, “well, I have a use for Fabian Cortez.” And I was like, “brilliant! Have him. Great!” And I guess at some point I can have him back, but we’ll see if I have a use for him. But…I’m trying to remember how this rambling sentence started. I was about to explain where Mysterium came from.

Rabiroff: Yes.

Ewing: So, I got into writing issue #1, and the idea was that they’d do a big mission — originally it was just going to be Manifold, but I thought, that’s a bit rubbish if it’s just one guy. So we’ll have to do a mutant circuit, like The Five. There are five of those, let’s do six, and we’ll bring in all of these fun characters. And it will be a good opportunity to do more stuff with the Far Shore, and the Mystery, and all of this stuff that I’ve been sort of, you know…[laughs] “you’ve been trying to make ‘fetch’ happen forever.”

Because that [Avengers: No Surrender] was the first time, and I was always thinking, at some point, in some future book, somebody is going to have to go in there. And I was like, here we are, it’s S.W.O.R.D. #1, they need a big mission, they need to get the super-metal from somewhere: let’s make it them. Let’s make them go in and see what’s in there. And it’s a very bright, white light, and some stuff that I think readers are still puzzling out to this day.

I Don’t Do This Stuff With a Plan

Al Ewing

Rabiroff: Do you have an answer in your mind for how this all lays out in your cosmic schema?

Ewing: I’ve definitely had Doom say the Mystery is the Above Place, for want of a better word. Which is like Jim Zub’s House of Ideas, and…you know, all of those came from an old Mark Waid issue — obviously I worked with him on that [Avengers story] as well — where the Fantastic Four meet God and he says, “How far out is the world that’s coming…the mystery intrigues me.” Which is a great sort of Kirby reference. And it’s like, what is the mystery that intrigues God? That’s fantastic.

And then when it came time to do the last issue of The Ultimates2, instead of a recap page, I had the voice of The One Above All. And I’m a big fan of Philip K. Dick, and probably my favorite thing that he wrote (aside from his description of the giant metal face in the sky) is that chapter heading from Ubik where he says, “I am Ubik. Before the universe was, I am. I made the suns. I made the worlds. I made the lives and the places they inhabit; I move them here, I put them there.” I’m always quoting that.

So I wrote a little speech for The One Above All that had that flavor: “I am The One Above All. I see through many eyes. I build with many hands. They are themselves, but they are also me.” Because The One Above All is all of the writers, artists, editors, and readers, but also this sort of gestalt entity. No one person could direct the Marvel Universe, so it’s this…

Rabiroff: A creator that reflects its creation.

Ewing: Yeah. I think the first time The One Above All is mentioned is Uatu saying, “oh, there is only one who is above all, and his only weapon is love” which wasn’t meant to be anything, but it became something. And I see that happening all the time now. I’ll do something that I just feel is a nice moment, and somebody will pore over it with a magnifying glass and say, “well, obviously it’s this!”

But the Mystery: I’d already done a bunch of stuff with the Outside, which is Jonathan’s White Space, and just tying all this stuff together. But I had this idea that the mystery was this place you could go into and explore, this sort of creation zone. And I think I kind of implied that it was also the White Hot Room? So that’s a whole thing.

You know, I don’t do this stuff with a plan. I really don’t. I didn’t write that speech for The One Above All — I just wanted to do a recap page. You were talking earlier about the numbers of the cosmos. The reason that it’s the Eighth Cosmos is that there is a video game token called Iso-8, and I was writing a Contest of Champions book at the time based on the video game. And I was writing The Ultimates at the same time, so I was like, “okay, Iso-8 is what Cosmic Cubes are made out of, because it’s eight points so it’s a cube, and also the reason it’s Iso-8 is because this is the eighth multiverse. So the one that we just had is the seventh, and then Galactus came from the sixth. So that’s fun, there must be five more.” And then that was what Ultimates ended up being about. So someone in Burbank, or Palo Alto, or wherever these games are made came up with Iso-8, and now Marvel’s entire cosmology is based on that. And the nice thing is, you can do all this stuff, and it’s so big that it doesn’t really affect anyone else.

Rabiroff: So when you introduce concepts like that, that at least in theory are going to define the broad cosmology of the Marvel Universe, is there any editor looking over your shoulder saying, “you can do this, you can’t do this,” or do they just let you run free?

Ewing: Not really, because I’m not the only one. Peter David’s done a lot of stuff about the afterlives, what death looks like. The Children of Eternity. People come up with big stuff, because big stuff is fun to come up with. I’ve had the advantage of sticking at it, because I’m off to the side a bit generally. So, as I say, stuff doesn’t really affect people in a real way. If I were to come up with, say, a new secret spy agency, you need people to buy in on that.

Only one person, it might have been Mark Waid, used W.H.I.S.P.E.R., God bless him, so I thought, “okay, I’ll just give them back to A.I.M.” And then it’s like, Sunspot had A.I.M., and I’m seeing a lot of yellow jumpsuits in other books, so I thought, this one’s not going to stick, let’s put it back. And, you know, that’s fine. That’s how it is. But the advantage of the really big stuff is that it’s almost too big for anyone to contradict. Because if people do stuff that is as big, at that size nothing can really contradict each other, because it’s all just different facets of the same thing. It becomes more about joining the dots between concepts, and that’s a fun exercise for the reader to do that. But I’m under no illusions about this stuff outlasting me. The big concepts — Order, Chaos, that sort of thing — I feel like they have fallen out of fashion a little bit.

Rabiroff: Why do you think that is?

Ewing: I don’t know. So many of these are Jim Starlin creations, and I kind of feel like recently there’s been a sense that he should be the one to tell his own stories. But even aside from that, it’s like they’re from one man’s imagination and one man’s view of the world, and where Jim Starlin was at a particular place and a particular time he was writing these comics. And this comes back to how so much of this stuff is synchronicity and serendipity. I’ll just have an idea while I’m writing, and in it goes. Sometimes even in the lettering draft, I’ll come up with one of these hifalutin phrases and think, “ooh, that sounds good.”

But there’s a sort of shelf life to these ideas, and at a certain point they almost start to be restrictive. I always get people asking me about Oblivion, who’s this guy with a tablecloth for a face. And people ask me about him because in an Iceman miniseries from the ‘80’s, J.M. DeMatteis puts words in his mouth that are like, “oh, before there was anything there was absolute Oblivion.” So it’s like, “well, he’s even bigger than The One Above All!”

And I feel like that’s what all this stuff turns into over time. It starts off as people attempting to get at some inner or outer cosmic truth — you can’t tell me that Jim Starlin wasn’t trying to get at something major in his mind or in his life. And when Kirby made Galactus, that was him and Stan Lee attempting to find the face of God. And you can see in the fallout over the Silver Surfer, when they both have these vastly different ideas of what the Surfer represented, but they were both these vast ideas. But time passes, and they just become baseball cards and action figures. And once someone is arguing whether Oblivion could win in an arm wrestle against the In-Betweener, it’s like…

Rabiroff: …does it even really matter as a cosmic concept anymore?

Ewing: And somebody like Jim Starlin can come back and tell a really personal story with those characters, but I don’t know if the rest of us can really do that anymore.

Rabiroff: Aren’t you sort of describing the process of actual religious theology? That it starts with something big, and ineffable, and mystical, and then becomes systematized into rules, and regulations, and things that are quantifiable. Until it feels too prosaic and you need to mystify it again.

Ewing: Yeah, I hadn’t put that together, but yeah. I’m an agnostic in the truest sense. I went off atheism, the really hard kind, probably because that particular brand of atheist were just kind of internet assholes for a while. So I guess in a lot of the stuff I do, there’s a desire to at least consider this stuff, to at least approach it. But I almost feel like claiming knowledge of this stuff feels like an act of hubris.

When you look at the Starlin stuff, or Steve Englehart, or Steve Gerber — Marvel in the ‘70s — there’s this tradition of trying to get to the bottom of something through the tool of superheroes. And I like that. I think that’s worthwhile. And if you end up having any kind of enlightenment, that’s a bonus. But it makes for really good comics.

Zach Rabiroff edits articles at Comicsxf.com.