Professor X promised there would be no prisons on Krakoa. He lied. Sabretooth was the first mutant sent to the Pit. Now he welcomes five more mutants into his own private hell. What laws did they break? Are they ready for what they’ll find? Sabretooth #2 continues digging into Krakoan justice. Written by Victor LaValle, drawn by Leonard Kirk, colored by Rain Beredo, and lettered by Corey Petit.

Jude Jones: “I am what time, circumstance, history have made me, certainly, but I am also much more than that.

So are we all” – James Baldwin

A few weeks ago I reviewed Voices, Marvel’s showcase for Black talent. And while I generally enjoyed it, I noted that a real commitment to Black Voices comes from hiring Black people to do real, long-form stories.

Stories that don’t just focus on Black people (although Black people should be included because we are, you know, actual visible people). Stories that use a writer’s experience and understanding of the world to shed new light and perspective on characters. Stories that aren’t disposable one-offs; stories that matter, explicitly.

Stories like Victor LaValle’s Sabretooth.

A woman once told me that women had to be experts on the way men think in order to survive a world dominated by men. I believe this is true of many underrepresented populations; we have to be more perceptive of the world in order to survive it. I argue that this is specifically true of Black people, who are often the canaries in the mine of America. Out of necessity, we feel the world deeper; and when the world exposes her sharp edges, it cuts us deeper, which makes our prose richer.

I’m not, of course (of course!), saying all Black writers are excellent or that no white writers can feel; I am saying that the world affects different people differently, and we are all best served when those differences are exposed and expounded upon on paper.

The world doesn’t play by the same rules with everyone; thus everyone will experience the world, in vastly different ways. Even experiences that are supposed to be neutral and blind.

And that idea – that rules apply differently to different people – is what makes Sabretooth #2 such an engaging read.

Anna Peppard: At first, this issue struck me as less monumental than the debut, which is, in some sense, inevitable. But this issue is growing this comic’s world and fleshing out its characters in ways that remain fascinating and vital. This issue also pushes forward with connecting Krakoan (in)justice to real-real contexts of the same, which we’ll be highlighting throughout this discussion. X-Men comics have often been criticized for the messiness of their metaphors, but so far, this comic is an example of metaphor done right, using fantasy to illuminate rather than avoid social realities while still telling an engaging character-based sci-fi story.

Jude: So as we read this, as we think through this, as we feel this, think not just think of this writer or of this character.

I want you to think of Kalief Browder.

Not all of us

Kalief, a 16-year-old on probation for a crime he may or may not have been involved in, was arrested for stealing. Despite the uneven testimony of his accuser, despite not having any stolen items on him, he was arrested. Because of his previous infraction, he wasn’t eligible for bail.

Because he was the wrong person at the wrong place at the wrong time, he was forced to sit in jail, with grown men, at 16 years old.

Kalief’s circumstances were certainly not unique to him in our world; and through the lens of this comic, imprisonment on flimsy charges, done without trial or due process, is sadly precedent.

Jude: Think about all of the other characters sentenced to the Pit: All were brought before the entire Council, where the entire Council had to sign off on those members being sent to the hole. But here, poignantly, there is no Council. There is no dissenting vote from Kurt or Ororo. There is only Magneto and Xavier, delivering a verdict with contempt and conceit. Why is the process different for these mutants as opposed to the others? I have an idea; I’ll come back to it later. For now, note the numbers over their heads, denoting which of the three laws they broke: (1) Make more mutants; 2) Murder no man; 3) Respect the sacred land. Note the wildly different facial expressions of the two offenders “convicted” of murder: anger and conviction in Nerka’s face; note the hesitation, if not fear in Oya’s eyes.

Something about this – the group judgment, the laws broken – feels off. Part of me – and I’ll spoil my thoughts here – thinks this *entire* comic is a meta dream of Sabretooth, a la the layers of dreams in the movie Inception (braaaaam). But even if I’m mistaken and that’s not the case, something still feels wrong about all of this. What do you think, Anna?

Anna: I had a similar thought. There’s a lot that doesn’t quite add up in this scenario. The laws of Krakoa have previously operated flexibly at best, with their specific meaning up for debate. Remember how Way of X suggested “make more mutants” refers to mandatory breeding? I (unfortunately) do. But if that’s what the law means, Stacy X and lots of other mutants have been serially breaking it, and even Nightcrawler, the creator of the law, has seemingly forsaken it. As we pointed out in our last column, characters like Logan also break the “murder no man” law pretty frequently. Granted, as Jude notes above–that’s how “justice” tends to work in the real world, which is to say “selectively.” And maybe that’s the point.

Except that makes more sense for Sabretooth than the other characters sent to the Pit. It’s not morally right, but makes narrative sense, for Xavier et al to make an example of Sabretooth, a longtime antagonist who’s proven, time and again, that he’s not interested in cooperation or redemption.

If parts of this scenario end up being illusions, it would let LaValle criticize Krakoa’s power hierarchies without negating the good things this place does or might mean in other comics, for other characters and readers. That might sound like a cop-out, but it’s not. Doing genuine critique within shared storyworlds that are also brands is extremely difficult. If LaValle can continue making us question this space–and the cultural context(s) surrounding it–without breaking it, I’ll only be impressed.

He’s Here

Kalief was arrested in May of 2010. For years – through changing trial dates, though plea deals, through surviving in an environment where inmates and officers alike tried to break you – Kalief maintained his innocence. Just over three years – three years – later, because his accuser was no longer in the country (a fact the prosecution likely knew for a time prior), because the evidence was already flimsy, and because the attempt to break him was unsuccessful – Kalief was freed.

But the damage was done.

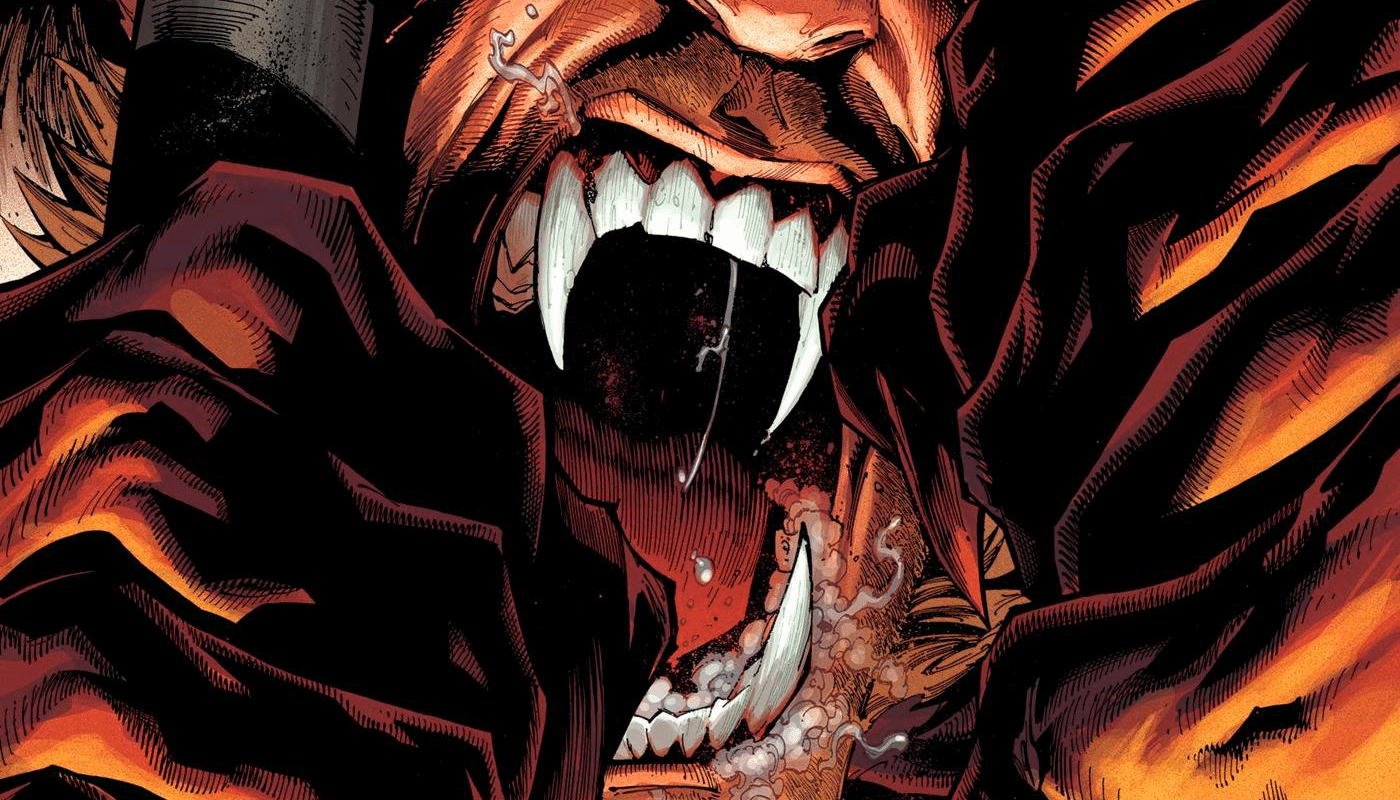

Jude: Our inmates/victims are now inside the (literal) belly of the beast, fighting Sabretooth on ground he’s not just covered but owned. And again, as we watch them fight, as we watch them act as a unit (mutant circuits!) to try to overtake Sabretooth, two things stand out. First, is there a reason, other than time, sheer willpower and hatred (which, to be fair, are quite the reasons!) why Sabretooth can control the inside of Krakoa and not anyone else? If they’re all hooked up to the same floral apparatus, that would imply they could all, if need be, manifest thoughts into power and action. So either Sabretooth really does own the land, or we’re just looking at an extended, elaborate figment of Sabretooth’s imagination. Second, note how the Feral Council is aware that Third Eye can see past the deception of Sabretooth’s manifestations. Note how they say “it doesn’t matter” because he’s still “food.” Note how Sabretooth is a master thinker and strategist, even if his diction choices seem untamed and juvenile.

Note how trust is not something to be extended to Victor. At all. Am I making sense here?

Anna: Definitely. I am similarly wondering whether we’ll eventually see other characters learning to manipulate this world–and wondering what they’d do with it if they could. The entire Krakoan era is a parable about the power, possibility, and danger of creating new worlds. Lots of potential to dig into those themes here.

Jude: Third Eye uses his powers – which, I’m guessing, use specific emotions (fear) to lock on to people. I’m sure this relates to his betrayal of “make more mutants” in some way – maybe he sparked/accentuated mutants’ fear of procreation? – but I’m sure we’ll find out eventually.

He locks on to Mole who is deathly fearful of Sabretooth. Why? Because Sabretooth, during his time as a Marauder, killed his friend and nearly killed him. It’s this persistent fear that allows Third Eye to manifest to Mole and ask (or encourage? We don’t know how his powers work!) Mole to get help for the incarcerated.

And you know how you probably didn’t know who Mole was until now? That idea of being unknown – unimportant – hinders Mole’s ability to get help. He’s summarily ignored by everyone on Krakoa, From Apocalypse (we miss you man!) to Ororo. And it’s this ignoring by the powerful I want to focus on for a bit.

Remember how these people – lesser-known mutants with lesser-known victims – didn’t get a full trial? Even Sabretooth – in all his clear villainy – got a full trial. It’s not just that there are separate rules for the good and bad mutants – there are separate rules for the unknown ones as well. For the ones who don’t have a name brand. For the easily ignored, the disenfranchised and disregarded.

The 16-year-old from the Bronx.

Anonymity brings apathy, and apathy of the state is central to any understanding of the plight of the disenfranchised. Victor got an unfair trial because he was inconvenient; the others didn’t get a trial because they were unknown.

Blind justice, indeed.

Anna: Since Third Eye quotes Jean Toomer while activating his powers, then visits Mole, a longtime sewer-dwelling mutant, while in a semi-transparent astral form, it’s perhaps not totally out of left field to link these happenings to another iconic piece of African American literature–Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, originally published in 1952. In one of this comic’s text pages, Mole describes living in the secret, forgotten worlds beneath New York City, which is not totally unlike Ellison’s narrator, who lives “rent-free in a building rented strictly to whites, in a section of the basement that was shut off and forgotten during the nineteenth century.” If you’ve read Ellison’s novel, you know it’s a complex, sometimes-surreal meditation on the meaning of visibility vis a vis race and class, wherein both visibility and invisibility are freighted with danger and dehumanization. The book’s final poetic lines are: “And it is this which frightens me: Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?” There are many ways to interpret those lines, but one possible meaning relates to the terrifying flexibility of human dignity; Ellison is betting too many readers will see themselves in his tragic narrator, and history has, sadly, proven him correct. If I were on Krakoa, I might be someone like Mole. (Most of us would be–the Council is the 1%.) Here’s hoping this world finds a way to do better for more mutants.

Jude: Excellent point about Mole as the literal Invisible Man, which happens to be my favorite book. That we’re never really sure how literally reliable the protagonist is as a narrator (partially because he’s slowly going insane; partially because the world he lives in is insane) also reminds me of Sabretooth.

Anna: Regarding Third Eye’s “crime”–if we have to revisit “make more mutants,” I’m hoping this story does something more interesting with this law than what we’ve seen in other comics. For me, linking that law to traditional biological reproduction is not only deeply troubling but also very boring. Surely the architects of Krakoa are capable of imagining something better than a society still beholden to heteronormativity and biological essentialism? I’m angling for Third Eye’s supposed crime having something to do with the resurrection protocols, which I originally assumed “make more mutants” pertained to. It’s also another area of Krakoan life wherein inequality is starkly evident.

Innocence won’t save you from incarceration

“Before I went to jail, I didn’t know about a lot of stuff, and, now that I’m aware, I’m paranoid.”

Kalief, who spent weeks in solitary confinement during his time in jail, attempted suicide twice while imprisoned. And though he was eventually released, the mental and emotional scars never fully left him. He passed away two years after being released, at his mother’s home, where she would discover his body.

Anna: We end this issue in (another) prison of the mind, but this one’s more literal. Creed proves himself adept at manipulating the space around them by creating the “Krakoa State Penitentiary,” an imposing, crumbling building fitted with searchlights and window bars, surrounded by a fiery barbed wire fence and choppy water. Xavier, of course, patrols the halls as the warden. But Xavier speaks in Sabretooth’s voice and is joined, at the insistence of the other prisoners, now wearing orange jumpsuits, by Magneto.

There are a few character-building things that stood out to me in this section. First, being in this recognizable prison brings the characters closer together. Creed wears the same orange jumpsuit as everyone else, suggesting they’re all equal here. But are they? Creed is still in control of this environment. I wonder if Creed is exploiting an illusion of shared disenfranchisement against a convenient enemy (Xavier) for his own gain. Second, Oya is not as “innocent” as people keep telling her she is. I don’t mean that in a moral sense; I don’t think she’s “guilty” or deserving of her current situation. But the way she talks about Xavier and Magneto, in this prison scene and earlier in the comic, shows she’s not shocked by the idea of being manipulated by one or both of these men. I like this read of Idie, which makes sense to me in the context of her previous experiences with some of the X-Men’s leaders (remember that time Cyclops basically ordered her to kill a roomful of Hellfire guards?). Third, Melter is clearly lying about his “crimes.” There’s more to this story, which we will undoubtedly learn in future issues.

Jude: As Black Columbo, err Easy Rawlins, err Third Eye revealed the true nature of their incarceration and Sabretooth’s apparitions to the group, the biblical hell turns into a more conventional one: prison. The wards of the state note that complicity is not just Xavier’s; that blowing up a rock, of all things, can get you sent to Hell. (which, again, is art imitating life); that innocence – both of the spirit and, if I can take the liberty of sensing a double entendre, of action – won’t save you from incarceration.

And thus Victor unites his fellow inmates to revolt against the system that conspired to send them away – just like Lucifer and his fallen angels.

Now, as a Christian, I’m ordained to believe that this revolt is futile – that the Lord will eventually reign supreme and victorious. But, of course that’s what the Lord would want one to think, isn’t it? Was Kalief saved? Did he not suffer? Was he not wronged? Are there not more Kaliefs being created daily?

Lucifer would object to this ordination. Sabretooth would too. Maybe I do too, which, unsettling as it is to empathize with Lucifer/Sabretooth, is why I look forward to reading the objection next month in Sabretooth #3.

New lights and perspectives in a story that thankfully, yet sadly, matters.

X-Traneous Thoughts

- Starting off your work with the Fredrick Douglass quote (“It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men”) that kept me motivated as I worked in education? Yes. Goodness yes.

- “Fear is a noose that binds until it strangles” – as we mentioned above, this line is courtesy of Jean Toomer, Harlem Renaissance poet, maybe best known for his experimental modernist novel Cane. Another fact about Toomer, which may or may not be pertinent – he was a very very light skinned black man who sometimes passed for white. That he could navigate between two vastly different worlds gave him a very unique, poinitant perspective; that Third Eye can navigate two worlds gives him the same.

- There’s significantly less violence here than the last issue, but Leonard Kirk’s work still leaves a haunting impression. His work here fits the more meditative vibe of the issue, and especially in facial reactions, effectively conveys the horror and sadness of the incarcerated.

- Still praying for Oya.

- If you’re so inspired, consider making a donation to the Kalief Browder Foundation here.