In a franchise that has run for over 50 years, there is bound to be debate about which story is “the best”. Listicles will be written, podcasts will be recorded, debate will be never ceasing. In this series, we’ve gathered ComicsXF writers to share what they personally think are their best X-Men stories ever.

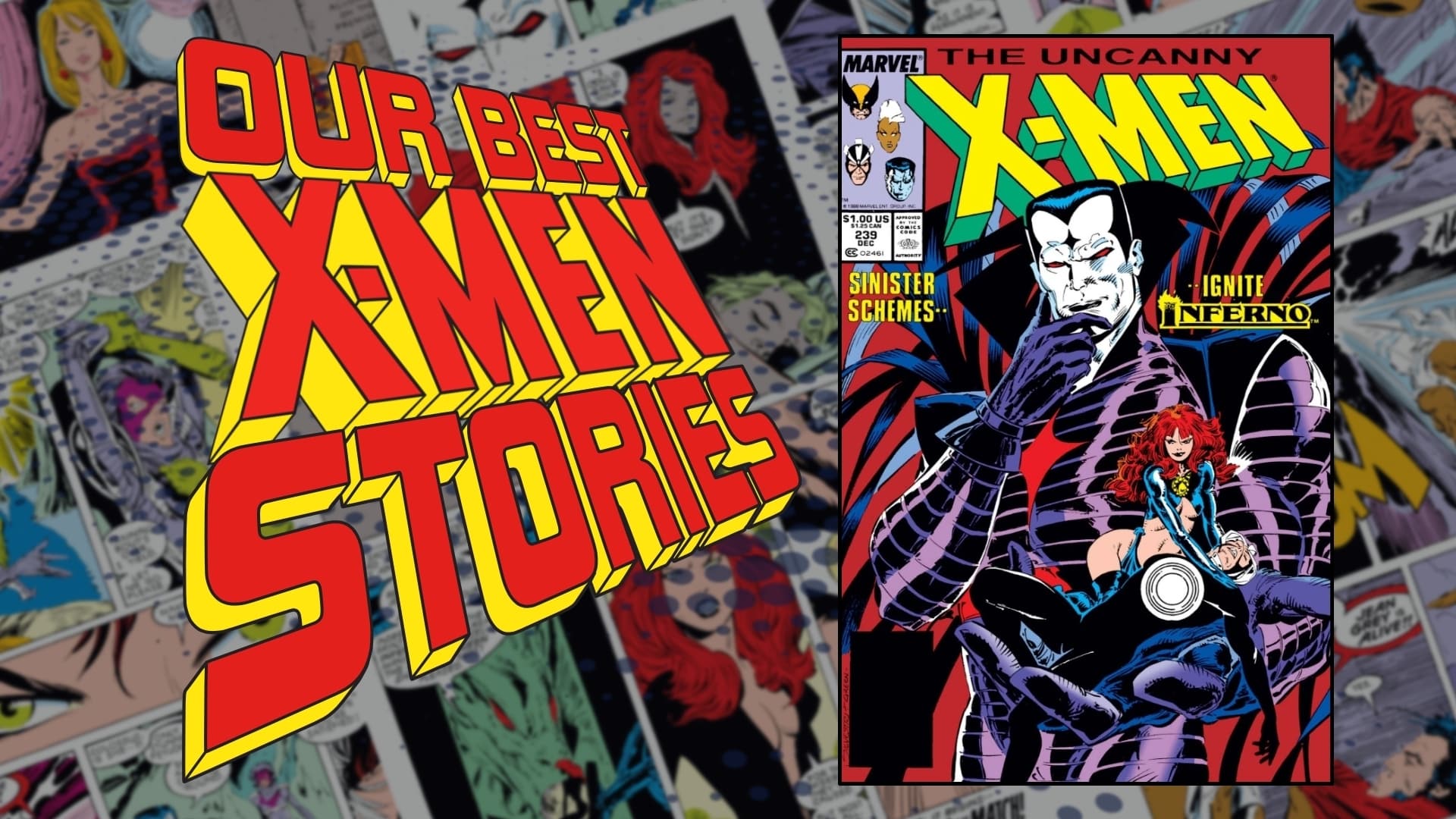

Uncanny X-Men #239 (1988) “Vanities”, written by Chris Claremont, penciled by Marc Silvestri, inked by Dan Green, colored by Glynis Oliver, lettered by Tom Orzechowski.

We’ve both been hurt—betrayed by those we loved. Is it so wrong to seek a little solace to ease that pain?

If a new reader asks me to identify the best X-Men story by Chris Claremont, I’ll point them to Uncanny X-Men #205, “Wounded Wolf” (1986), a beautifully contained treatise on the fundamental themes of heroism and the cycle of violence that drive the so-called “Mutant Metaphor” of X-Men comics. It’s not my favorite, though. For the past 4 years, I have written about Claremont’s X-Men each and every day on a micro-blogging Twitter project called “The Claremont Run” (@ClaremontRun). I am in way, way too deep on my subject, but when you’re already out in the depths, as I am, the best stories aren’t the ones that are contained. Out in the depths, the best stories are the ones that reward your immersion in those depths. To my mind, “Vanities” from Uncanny X-Men #239 (1988) is a comic book that provides that reward, better than anything Claremont has ever written.

A main impetus of my Claremont Run project was the observation that Claremont is widely praised for his mastery of long-form storytelling, a mastery that’s impacted the modern media landscape far beyond the world of comics. Yet most comics courses that study Claremont will focus on God Loves, Man Kills (1982) or the “Dark Phoenix Saga” (1980), as will, quite frankly, a disproportionate amount of comics research. That’s a problem. Both of those stories take place in the first half of Claremont’s epic 16-year run. And both can (arguably) be read in a fairly contained way. You can sell a Dark Phoenix Saga trade to new X-Men readers. You can teach it to a class of undergrads, as I have done. “Vanities,” however, comes from the back half of the run, and showcases the long continuity aspect far better than the more-studied X-Men works. It launches the reader into the longest and most ambitious cohesive story arc in the history of X-Men comics: “Inferno,” a 52-issue storyline spanning 13 Marvel titles.

But even that quick math is underselling the scope of the project. In some volumes, “Vanities” is considered the beginning of Inferno, but that’s not accurate. Inferno begins with “The Mutant Massacre,” another crossover series in which Mr. Sinister’s Marauders first enter the scene by attacking and killing the Morlocks. That’s not right either, though. Inferno is about Madelyne Pryor’s revenge for being abandoned by Cyclops when X-Factor formed. But if that’s true, then it’s actually about Scott and Madelyne’s overall relationship, which starts in Uncanny X-Men #168 (1983). That’s not right either, though, since Inferno is also very much about the Phoenix, which is the literal source of Madelyne Pryor’s life force when combined with Sinister’s genetic engineering. So the story extends all the way to the Dark Phoenix Saga, which, as I have argued before, can be more accurately perceived as a holistic “Phoenix Saga,” since its symbols work best when integrated into the much broader story of Jean’s initial Phoenix transition. THAT story begins in X-Men #98, Claremont’s second issue as solo writer of X-Men… in 1976. Long story short: Inferno is the culmination of 12 years of comics, and “Vanities” is the flashpoint.

And it’s a really compelling flashpoint, one that uses all those years of continuity and character development to establish tension, stakes, and symbolic richness to the broader aims of the Inferno crossover.

The creative team is at the peak of their game. The letterer and colourist are Tom Orzechowski and Glynis Oliver, respectively, each longstanding Claremont collaborators, and each regarded as elite artists in their respective fields, so much so that Claremont actually went out-of-pocket in order to keep them on his books. On pencils we have Marc Silvestri, whose gritty, Frazetta-influenced style makes a perfect showcase for both the dusty Outback era of X-Men and for the demonic hellscapes and scenes of moral degradation that define Inferno. His partner, on inks, is Dan Green who is, at this point, deeply in-sync with Silvestri’s pencils, lending weight and finding shadows in order to embellish Silvestri’s sketchy style. In a few months time, the series would transition to bi-weekly issues and the production schedule would necessitate some artistic compromises, taking away from what was a wonderful visual pairing, and thus making this era, in my eyes, their creative highpoint.

The issue is structured around a series of character vignettes–brief scenes that showcase just how good Claremont was at juggling his large and diverse cast. Each character gets their own individual beats and moments. This personalizes the forthcoming battle for each of them, while coalescing all of their stories around themes of moral corruption and, as the title denotes, personal vanities. This concept of vanity is what creates cohesion across the vignettes, all of which explore how a sense of self-regard or esteem can lead toward a sense of entitlement. It’s through those entitlements that the conflicts arise, as character after character crosses slight moral boundaries, setting in motion complex sequences of events with catastrophic end results.

“Vanities” opens with two prologues. The first is a horrifying depiction of a family of tourists amid a New York City that is transforming at an ominously slow speed. They step into the elevator of the Empire State Building and start screaming as soon as the doors close, then beg “for the love of heaven have mercy!” just before blood rushes through the crack of the doors. It’s a graphic and terrifying opening–something you’d expect from Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing or Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, not so much Claremont’s Uncanny X-Men. As such, this prologue signals a shift in tone, pushing the series into unfamiliar territory as if the book itself were subject to the same moral corruptions that its heroes are facing.

The second prologue is a brilliant portrayal of Mr. Sinister, pining in a state of grief and even depression for his knowledge that the X-Men are dead and he’ll never be able to oppose them. Ponders Sinister, “I feel cheated and somehow diminished.” Sinister has never even met the X-Men at this point. His sulking is thus an unusual bit of characterization that draws on dramatic irony (the reader knows the X-Men still live), creating a tense delay of anticipation. Sinister then has an encounter with one of his lackeys, Malice, that again draws out the themes of corruption, devil’s bargains, and subtle transformations, all while showcasing Sinister’s pathological capacity for manipulation through abuse followed by sweetly worded distortions. As Malice departs, placated, Sinister muses: “Vanity, oh vanity—the key to a person’s soul and thereby to dominance over them.”

After all this stoking of dread through both setting and villain, the issue counterintuitively transitions to a scene of the long-suffering Dazzler having the most euphorically joyful night of her entire life, surrounded, as she is, by love and music and validation as she performs her heart out at a local dive bar. And again we feel the dramatic irony, because we know what’s out there waiting for her—that this joy she’s experiencing is a luxury that will soon be taken from her. Claremont also connects Dazzler’s joy to his devil’s bargain theme with the narrative caption “she’d cheerfully give her soul to have it last forever.” The vulnerability created by this act of vanity is established in the adjacent panel, which shows Sinister snapping his crystalline Dazzler figure in half.

From this sinister subversion of Dazzler’s joy we skip to Havok taking a self-flagellating jog to deal with his figurative demons before being confronted with a more literal one. Madelyne Pryor, who, at this point, we know has made a pact with a demon, arrives in a flash of light that vaguely resembles the Phoenix flare. Havok is then seen in shadow taking her hand on bended knee. He isn’t proposing, just crouching, but the visual symbolism initiates a thread of matrimonial imagery that subsequently unfolds in a perfectly linear fashion. Madelyne and Havok next take each other’s hands and profess their care for each other (Havok says “so do I” instead of “I do,” but we get the picture). This is followed by a wedding dance in Havok’s dream sequence, with the narration, “Darkness all around looming, threatening, closing in. Only natural that he hold out his hands, that she take them. All they have left is each other. Small wonder they hold on for dear life.” In the real world two pages later, they cross the threshold to consummate the symbolic marriage in reality. Silvestri/Green/Oliver illustrate the sequence by creating a juxtaposition between the vibrant light of the Australian sun (which Havok is literally sunbathing in) and the darkness of the bedroom that Madelyne leads Havok into. As a result, Madelyne is seen to quite literally seduce Havok out of the light and into the darkness. And thus Havok unknowingly becomes Madelyne’s Goblin Prince.

Narratively amid and formally between Havok and Madelyne’s story, we’re also offered a poignant vignette that has Storm learning that her dear friend Jean Grey is alive again. Storm erupts with emotion at this revelation, violently turning on Logan for the secrets he’s kept from her, secrets that he holds because of his inability to engage emotionally with the return of someone he loved (a rare showing of vulnerability for Marvel’s most invincible mutant). “Gimme a break, darlin’,” says Logan. “I was scared. Still am. I loved her, Ororo. I lost her.” Interestingly, the visual imagery shows Logan’s face drenched with rain (a shower caused by Storm’s out of control emotion), thus creating the appearance of open crying on Wolverine’s part.

This scene also highlights the dualities that give Claremont’s characters so much depth and richness. It is the shy and reserved Ororo who flies off (quite literally) into a rage, while the berserker Wolverine is calm, sorrowful, even pitiable.

At the same time in yet another different space, we find Rogue, Colossus, and Psylocke sparring. Tempers quickly flare, with both Rogue and Psylocke losing their cool. This foreshadows the emotional corruption effect that Inferno will have on the X-Men, turning long-simmering animosities (and the vanity that informs these grudges) into full-on throw-downs as everything boils to the surface and everyone turns on each other. “Armor’s only protection you got,” Rogue tells Psylocke as Rogue pins her to a wall. “Ah could peel it right off without you doing a blessed thing to stop me.” Psylocke politely asks Rogue to let go of her, at which point the next panel becomes a long horizontal extreme close-up of Rogue’s unflinching eyes as she dares, “Make me.” Psylocke responds by telepathically knocking Rogue unconscious. When confronted about hitting her teammate too hard in a training exercise, Psylocke replies, “she was asking for worse.” The scene draws out an atmosphere of unease, of an ominous shift in the emotional current of a book generally oriented around the concept of found family. These subtle cracks in that veneer thus serve as portents of impending doom.

The final two pages of the issue reveal Sinister has possession of Madelyne’s baby. This establishes the inevitable collision course between Sinister and Madelyne as well as the involvement of N’astirh, yet another villainous player who declares his own ambitions on the same page. Then we return to Australia for a beautiful and emotionally ambivalent postcoital scene, revealing at last Madelyne’s completed turn to the dark side, visually signalled by a fully formed Phoenix force in her eyeball that connects an already complex story to that broader Dark Phoenix continuity. Hovering over her lover, Madelyne reveals her corruption and intentions with some truly sterling Claremontian monologuing:

“How easily and naturally, Alex, you sleep the sleep of the just and innocent. I should be so lucky. Should I envy you your dreams or would you envy me the fact that I have none? Another time, another place, who knows what might have been? Here and now who can say what yet will be? I could save you. But it’s best that I don’t.”

For me, in this moment, the unique tenor of the Goblin Queen flares to life, expressing the heart of the character. She is everything at once: hero and villain; lover and destroyer; victim and victimizer; angel and devil. Despite being arrayed in the most obvious villain-coding through her allyship with demons, Madelyne is easily, in my eyes, Claremont’s most deeply sympathetic villain. It’s no wonder that thirty years later, X-Men fans still cry out for justice for Maddy.

“Vanities” isn’t the end of Madelyne’s story, or even its climax. But it is her tipping point, and watching that transition occur while knowing the only place it can take her–that’s long been a deeply powerful moment for me, as both a scholar and a fan.

And that is how the most ambitious crossover of Claremont’s run launches itself into greatness–with a narrative that, instead of shying away from the supernatural, expertly attaches it to a deeply nuanced human story while integrating a decade’s worth of character and plot building. We have clones, cosmic beings, mutants, poltergeists, and demons, yet the story finds its grounding in a simple tale of how our vanities can corrupt us, leaving us vulnerable to the moral degradations that are at the heart of the Inferno symbology.

Uncanny X-Men #239 doesn’t work in isolation, but isolated stories aren’t what made Claremont’s X-Men great. In my humble opinion as a comics scholar and lifelong fan, the greatness of Claremont’s X-Men lies in the unrepentant complexity of his continuity and the depth that complexity affords his storytelling, a depth that, in stories like “Vanities,” poignantly rewards the reader for the effort of playing in the deep end.

J. Andrew Deman

J. Andrew Deman is a member of the English Faculty at St. Jerome’s University and the Project Lead for“The Claremont Run”a large, mixed methods research project on the subject of Chris Claremont’s 16-year run on Uncanny X-Men. He also co-hosts the Oh Gosh, Oh Golly, Oh Wow! podcast.