In a franchise that has run for over 50 years, there is bound to be debate about which story is “the best”. Listicles will be written, podcasts will be recorded, debate will be never ceasing. In this series, we’ve gathered ComicsXF writers to share what they personally think are their best X-Men stories ever.

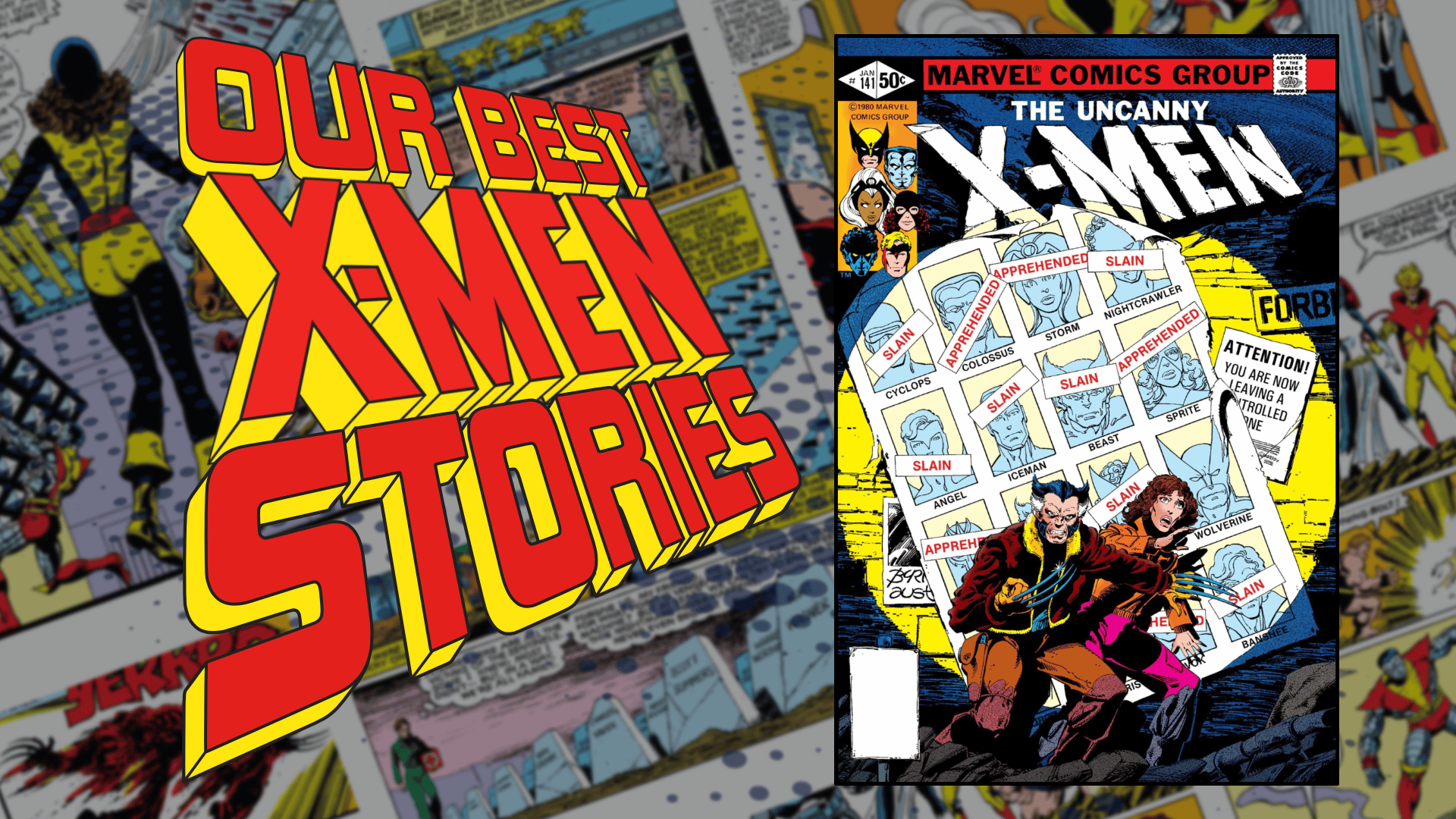

Uncanny X-Men #141-42 (1981), written by Chris Claremont, penciled by John Byrne, inked by Terry Austin, colored by Glynis Wein, lettered by Tom Orzechowski.

Today, the concept of the X-Men as a group of heroes “sworn to protect a world which fears and hates them” is well-trodden ground. The idea of mutants as an oppressed minority fighting against subjugation and extermination underscores countless comic book stories and has found its way into animated and feature film adaptations. But that wasn’t always the case. The concept of mutants, beings who are born with extraordinary abilities instead of developing them through specific atomic age accidents, is present in Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s X-Men #1 (1963), as is Magneto as a supervillain who believes in mutant dominance. But the “mutants as a feared and hated Other” metaphor is notably absent. One of the more amusing moments in that first issue is when the ranking officer at Cape Citadel simply stands aside to let some mysterious masked teens take charge of the assault on Magneto; he cares less about the X-Men being mutants and more about making the situation not his problem.

Before departing the series he helped create, Lee would plant the seeds for the minority metaphor, introducing it alongside the villains who’d come to personify humans’ fear and hatred of mutants: the robotic Sentinels. In X-Men #14-16 (1965), Lee along with artists Kirby and Werner Roth (as Jay Gavin) introduced Bolivar Trask, an anthropologist (and apparent roboticist) who created the Sentinels in response to what he saw as the threat represented by mutants. Embodying the darker elements of humanity’s desire to coldly exterminate mutantkind, the Sentinels, built and/or operated by various masters, would repeatedly battle the X-Men throughout their history.

One such battle occurs in Uncanny X-Men #141 and #142 (1981), the famous and acclaimed “Days of Future Past” storyline. Practically and symbolically, Days of Future Past is both a beginning and an ending. The “uncanny” adjective officially became part of the series’ masthead as of issue #142, signaling a commitment, at the level of branding, to Chris Claremont and Co.’s massively popular rejuvenation of the franchise. Days of Future Past also comes at the end of the beloved run by Claremont and artist John Byrne. One issue would follow before Byrne left the series, and in many ways, Days of Future Past is a capstone to their long collaboration, during which they revisited and put their own spin on many classic X-Men stories. Riffing on the work of previous creative teams like Lee and Kirby as well as Roy Thomas and Neal Adams, Claremont and Byrne’s run features their versions of a Magneto story and a Savage Land story and even, in the concurrent pages of Marvel Team-Up, their own Living Monolith story. Days of Future Past represents their riff on both a Brotherhood of Evil Mutants story and a Sentinels story. But beyond serving as the climax of the Claremont/Byrne run and the last of their efforts to put their stamp on the X-Men franchise, Days of Future Past is notable for being the single most important X-Men story of all time.

In its tight two parts, DoFP introduces readers to the then-far-off future of 2014, a world in which the mutant-hunting Sentinels have conquered North America, plunging the US into a harrowed dystopian state in which mutants are rounded up into extermination camps. Most of the X-Men are dead. The few survivors, including a gray-templed Wolverine and a wheelchair-bound Magneto (a key touchstone moment in Claremont’s long-form development of Magneto), escape and enact a plan to save their world: send the consciousness of the adult Kate Pryde back in time to the occupy the mind of her thirteen-year-old self, then just a neophyte member of the X-Men (Kitty Pryde had formally joined the team just two issues before DoFP began). There, Kate-as-Kitty will work to prevent the events which led to the rise of the Sentinels from coming to pass. Meanwhile, back in the future, her teammates will storm the Sentinels base inside the Fantastic Four’s former headquarters, buying Kate time to succeed in her mission to alter their reality.

The present and future storylines narratively and formally intertwine in pulse-pounding and heart-wrenching ways. While Kate-as-Kitty leads the present-day X-Men in a battle against Mystique’s new Brotherhood of Evil Mutants to prevent the assassination of mutant-hating Senator Robert Kelly (the event which leads to Kate’s dark future), readers watch as the X-Men of the future are brutally slain by the Sentinels. Storm is impaled by a massive harpoon. Colossus is vaporized. Wolverine’s skin is flayed from his adamantium bones. In the end, the assassination of Senator Kelly is averted, but it remains (intentionally) unclear if it was enough to stave off the dystopian future. Most importantly, the present-day X-Men—and, by extension, the readers—are left newly wary of what the future might hold for the X-Men specifically and mutants in general.

Through this newly established threat, Claremont and Byrne firmly establish, for the first time, the stakes of the X-Men’s mission: if the X-Men are sworn to protect a world which fears and hates them, what happens if they fail? Thanks to Days of Future Past, the answer is crystal clear: extermination. Prior to DoFP, the fight for Professor Xavier’s dream of peaceful coexistence between humans and mutants was largely a philosophical one. They fought to prevent the domination of humanity by mutants like Magneto or Mystique’s Brotherhood. Failure meant a world where humanity was subjugated—but the X-Men would probably still be alright. In this context, the X-Men were functionally pro-establishment. They fought against evil mutants to maintain the status quo, hoping to create a better world for mutants simply by example while fighting to protect humanity from those mutants taking more aggressive actions to either secure mutant equality or establish mutant supremacy. Days of Future Past changes all that.

Now, the X-Men are fighting for their own survival. Failure means not the subjugation of humanity, but death, of not only the X-Men, but of their entire species. Their actions are now working towards the creation of a world in which mutants are free from subjugation, free from the threat of extermination. When they take up arms against other mutants, it is to prevent those mutants from making things worse for mutants.

Moreover, the events of Days of Future Past directly connect the Sentinels to the establishment. Previously, they were created by and operated at the direction of a lone private citizen. Sometimes, the establishment turned a blind eye to that citizen’s actions, or even provided quiet but unofficial support. But if the X-Men took out the mad scientist behind the Sentinels, things would revert to the status quo ante. The threat of the Sentinels would fade, at least until the next misguided super-genius came along to revive them.

But in the future of DoFP, the Sentinels’ actions come, at least initially, at the tacit behest of the US government, in response to the assassination of Senator Kelly. They aren’t just weaponized expressions of humanity’s fear and hatred of mutants, they are now officially sanctioned weaponized expressions of humanity’s fear and hatred. The X-Men might be able to destroy one Sentinel or an entire batch of them, but their masters remain, because their masters are now an entire established system which explicitly fears and hates mutants. The Sentinels are just one tool of an establishment that is now explicitly anti-mutant.

This change drastically alters the position of the X-Men within their world, effectively transforming them into anti-establishment figures. They can no longer fight to preserve the status quo, because the status quo wants to exterminate them and their kind, something they know to be explicitly true thanks to the events of Days of Future Past. Decades of stories will follow in which the X-Men often question their effectiveness or their tenacity in continuing to fight in the face of ever-growing anti-mutant hatred. Because it explicitly shows the cost of failure and the cost of giving up, Days of Future Past looms large over all those stories. Its impact is inescapable.

Days of Future Past is an important story in so many ways. It’s the crescendo of one of the series’ most notable and acclaimed creative runs. It introduces characters who will become fixtures of the X-Men narrative. It features some of the most iconic images in the history of the X-Men, from the aforementioned Wolverine flaying to Kate Pryde walking past a cemetery filled with the headstones of her teammates, to the cover of issue #141, with an aged Wolverine caught in a spotlight in front of a poster showing various superheroes as either being caught or killed. Above all else, it tells a concise, exciting, and well-crafted sci-fi action-adventure story in its dense but perfectly paced two issues, taking advantage of brevity in the same way the similarly-acclaimed “Dark Phoenix Saga” by Claremont and Byrne took advantage of the long form serial nature of superhero comics. Dark Phoenix rewards readers playing the long game, while DoFP could be handed to a new reader and they’d have everything they need to enjoy the story.

But what makes Days of Future Past my best X-Men story is that its presence can be felt, directly or indirectly, in every X-Men story after it. The X-Men have (almost) always been sworn to protect a world which fears and hates them; this is the story which establishes, once and for all, what that means, and what will happen if the X-Men fail. It is the story in which the X-Men become the X-Men as they’ve been known for the ensuing forty plus years.

Go back in time like Kate Pryde and prevent the publication of Days of Future Past, and the X-Men wouldn’t exist as they do today. Like Kate hoped to do to her own timeline, the future of the X-Men would be irrevocably altered by its absence.

Austin Gorton also reviews older issues of X-Men at the Real Gentlemen of Leisure website, co-hosts the A Very Special episode podcast, and likes Star Wars. He lives outside Minneapolis, where sometimes, it is not cold. Follow him @austingorton.bsky.social.