In a franchise that has run for over 50 years, there is bound to be debate about which story is “the best”. Listicles will be written, podcasts will be recorded, debate will be never ceasing. In this series, we’ve gathered ComicsXF writers to share what they personally think are their best X-Men stories ever.

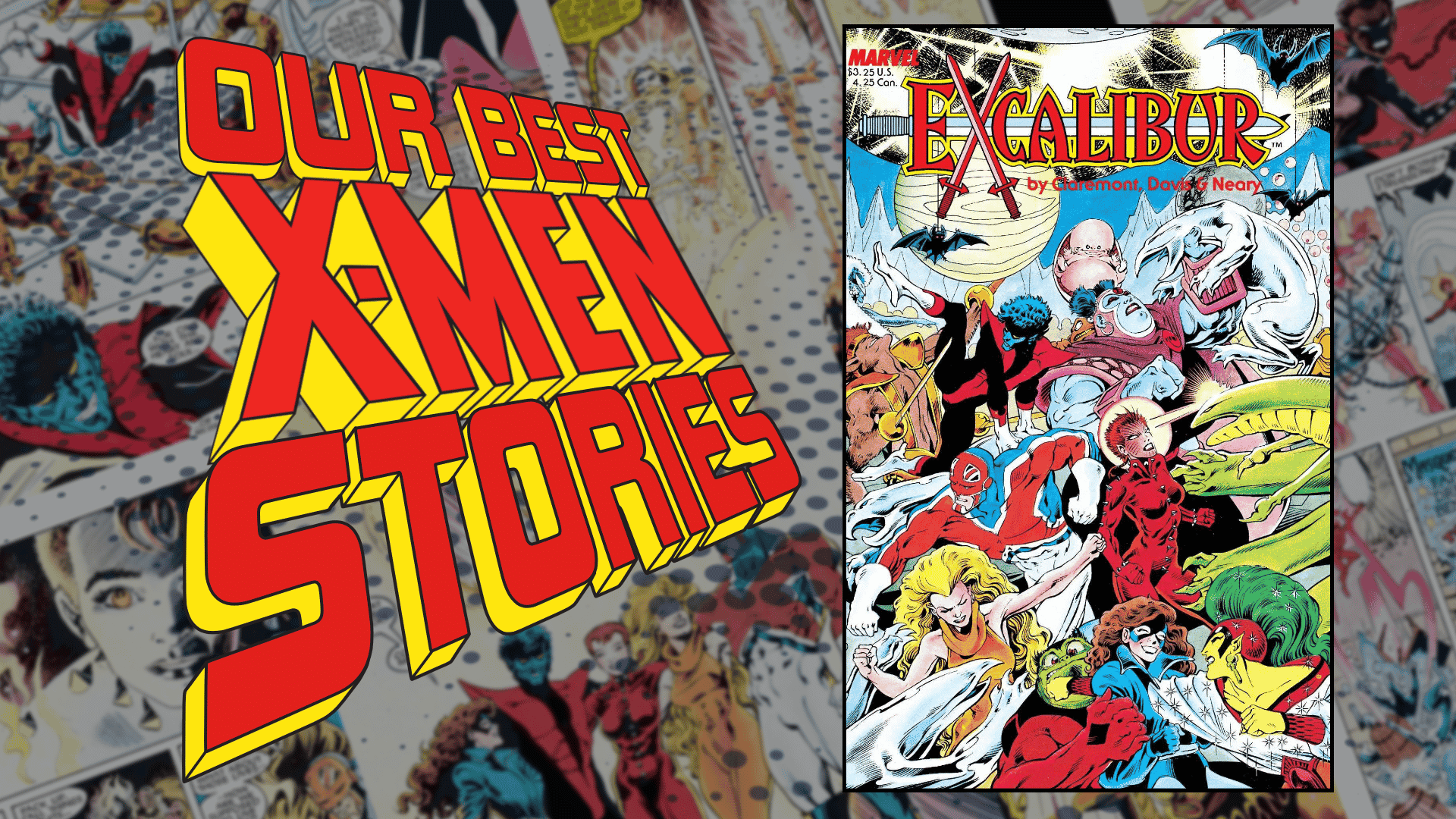

Excalibur: The Sword is Drawn (1988), written by Chris Claremont, penciled by Alan Davis, inked by Mark Farmer and Paul Neary, colored by Glynis Oliver, and lettered by Tom Orzechowski.

This article discusses self-harm.

Excalibur: The Sword is Drawn is a silly romp involving cosmic beings, surreal dreams, and two sets of intergalactic bounty hunters, one of which is made up of talking dogs resembling liquid mercury. It’s also a deeply human story about disability, trauma, grief, found family, and the struggle to keep going when you’re not sure why you should. In other words, it’s a great X-Men story, and my own personal favorite.

My favorite scene from my best X-Men story encapsulates why I love it. Surprising no one, it involves Nightcrawler. But it’s not the scene where he tosses Captain Britain in the ocean, or the scene where he makes a courageous, foolhardy attempt to stop the Technet from kidnapping his friends. My favorite scene is the one where Kurt Wagner nearly dies.

Kurt’s life isn’t imperiled saving the world, or a teammate, or someone who hates and fears him. Instead, his brush with death happens during a seemingly playful training exercise. Kurt can’t teleport to safety; his powers aren’t what they used to be. But he doesn’t need to teleport. He simply needs to stand. Yet in that moment, he can’t. This uncannily agile mutant, who generally jaunts through another dimension with little more than a thought, is powerless in a way superheroes seldom are. It’s shocking, heart-wrenching, and important—for Nightcrawler, for me, and for understanding why people like me can’t quit loving made-up mutants from thirty-year-old funnybooks.

The scene opens with some unusually spare and elliptical Claremontian captions, describing the location as, “Muir Isle… the gymnasium… fun and games.” Alan Davis’ images are considerably grander. Amid a tangle of metal pipes designed for climbing and swinging, Nightcrawler is suspended in midair, brandishing an épée in each hand and his prehensile tail, face algow with a devilish grin. He’s fighting gleaming golden robots decked out like swashbuckling musketeers. Each golden arm ends in a matching golden épée and each golden head is crowned by a red cavalier hat complete with voluminous ivory plumage. Why would Muir Island—or anywhere—have a fleet of rakish musketeer robots? (Or the capacity to produce solid holograms of them, which isn’t much different.) Because it’s ridiculous, and so is Nightcrawler. Of all the X-Men, Kurt Wagner is the most comfortable being fictional. While acrobatically sword-fighting the robotic musketeers, Kurt taunts them, comparing them and himself to other people who don’t exist, like Cyrano, Scaramouche, and Captain Blood.

For new readers, it’s an efficient introduction to Nightcrawler. For experienced readers, it’s classic Nightcrawler, meaning the version of Nightcrawler that’s celebrated in his first eponymous miniseries from 1985, written and drawn by his creator and biggest fan, Dave Cockrum. In that series, Kurt is debonair and fearless, a true swashbuckler and send-up of swashbucklers who bests the bad guy and gets the girl, then gets in over his head and needs to be saved by Kitty Pryde. But in 1988, classic Nightcrawler was a thing of the past. In the late-80s, Kurt had grown increasingly disillusioned with superheroing. This is on full display in 1987’s Uncanny X-Men #204, in which a doleful Kurt has brandy for breakfast before performing a pathetic reenactment of a scene from the ’85 miniseries, which concludes with his girlfriend turning away in disgust. Five issues later, in Uncanny #209, Kurt temporarily loses his teleportation powers in a battle with a confusing future-robot named Nimrod. This leads to a brutal beating by an anti-mutant mob in Uncanny #210. Then, in Uncanny #211, part of the “Mutant Massacre” event, desperation or guilt or some combination thereof compel Kurt to push his faulty powers to the brink, with catastrophic results. Before the debut of The Sword is Drawn, Kurt spends a year’s worth of comics in a coma, a symbol of the X-Men’s lost innocence and the new, realer stakes of a story that had become less about saving the world than mutants waging a never-ending battle for their survival.

Which is a long-winded way of saying that if you’d been reading X-Men comics prior to 1988, you’d be surprised by the appearance of classic Nightcrawler in The Sword is Drawn, and maybe relieved or excited. But you probably wouldn’t be shocked. Death rarely sticks for superheroes, and neither do disabilities. In general, but especially back in ’88, superhero comics embrace what scholar Rosmarie Garland Tomson calls a compensation model of disability. Tomson argues that within this model, “disability is a loss to be compensated for, rather than a difference to be accommodated.” This is based on the presumption that “‘disabled’ connotes not physiological variation, but the violation of a primary state of putative wholeness.” In other words, the compensation model views disability as a discrete injury to an otherwise healthy or “normal” body and encourages us to “get over it” by finding ways to make up for the loss. This ignores—or conveniently elides—the reality of disability, which can be accommodated and gotten used to but never simply erased. Along similar lines, comics scholar José Alaniz argues that superheroes with disabilities commonly resemble the cultural ideal of the “supercrip,” emblematized by athletes who garner praise for “conquering” their disabilities. In the eyes of its critics, writes Alaniz, the supercrip ideal is “a figure obsessively, indeed manically, over-compensating for a perceived physical difference or lack.” While some disabled people find empowerment in this ideal, for others, it’s a demoralizing, punishing standard wherein disabled people are required to do more, be more, try harder, in order to be treated as heroic, equal, or simply worthy of existing.

The Sword is Drawn attacks this problematic ideal by performing a spectacular double subversion. First, it subverts the expectation that Kurt shouldn’t be well. Then it subverts the expectation he’s become well, because it turns out, he isn’t. As he swings through his ridiculous jungle gym, a golden épée cuts him, slicing through his costume to expose his blue fur and a vivid slash of blood. In the same panel, Kurt’s devilish grin flips, becoming a devilish grimace. The sudden shock of his injury—which mirrors the shock we’re meant to feel at the equally sharp intrusion of consequence—prompts Kurt to teleport. Teleporting used to be easy, but since Nimrod and the Massacre and the coma, it’s anything but. Kurt falls, exhausted and disoriented, then finds he can’t get up. Or maybe, he doesn’t want to. As he struggles to reach the computer console that controls the deadly robots, he thinks, “Feel so weak—like all I want to do… is lie down and die.”

He survives because Kitty Pryde saves him (again), phasing through the wall to disable the robots who subsequently collapse in a messy heap, their resemblance to marionettes whose strings have been cut underscoring what should have been a laughable threat; in the end, the robots are merely toys. Kitty angrily accuses her older teammate of having a death wish, and Kurt doesn’t deny it. In a later confrontation with Brian Braddock, he even admits it. As he hurls a drunk and despondent Brian against the wall, Kurt declares:

“Sometimes, all I yearn for, more than anything, is to have been given the chance, the privilege, of standing with the X-Men and sharing their fate! It isn’t fair they’re dead, it’s far worse that I remain alive to grieve for them, because it’s more pain than I can endure!!”

In this comic, Kurt isn’t just struggling with physical limitations. He’s also dealing with grief and probable trauma, which is understandable when you consider everything he’s recently been through, including waking up from his coma to the news his found family, the X-Men, are dead. It’s a case of dramatic irony, since the X-Men aren’t actually dead; they’re just hiding out in the Australian Outback. But no one in the storyworld knows this, and The Sword is Drawn treats the deception as a genuine loss. Kitty cries dramatic, angry tears while clutching a photo of the X-Men in happier days. Brian’s face is a leaky mess as he drinks himself into stupor and erupts in violent rage at his girlfriend Meggan’s attempt to comfort him. And Kurt, historically the most optimistic X-Man, who’s adept at meeting hate with love and laughing in the face of danger—after losing his family and the joy he used to find in his extraordinary physical gifts, Kurt doesn’t want to get up.

I know how he feels. Thankfully, I’ve never lost multiple family members in an accident or suffered grave injuries that landed me in a coma. But five years ago, I did wake up missing something. At first, I was so nauseous I could barely stand, so dizzy I could barely walk in a straight line. These symptoms persisted, at varying intensities, for over a year. To say it was awful doesn’t cover it, especially during the eight-month period between the start of my scary symptoms and my hard-fought diagnosis. Turns out I have an unusually severe case of vestibular neuritis. In layman’s terms, that means I have extensive nerve damage in my inner ears, possibly caused by a reactivation of Herpes Simplex (the same virus that causes chickenpox and shingles). They’re tiny nerves, invisible on an MRI. But their loss packs a wallop. Basically, I suffered a sudden, severe loss of my sense of stability and balance. In effect, my brain and body were misaligned. Sitting still, I constantly felt like I was swaying. Lying down, I often experienced the shock of falling, heart racing with false panic. If I closed my eyes while standing, my ankles would tremble and start to buckle.

The treatment for vestibular neuritis involves retraining your mind and body to work together. This means a lot of balance and “gaze stability” exercises, many of which are incredibly tedious and make you feel worse after doing them. When the damage is permanent, you never really recover. The best you can do is get used to the loss. It works, but it takes time. For over a year, I struggled. I struggled a lot. I prayed to gods I don’t believe in to make the dizziness stop, even for an hour or a few precious minutes. I tried to imagine the future, but couldn’t; the only thing worse than what I was going through was the thought of going through it forever. At my lowest, I blamed myself for not getting better, and even for getting sick in the first place. Blaming myself offered the illusion of control; if it was my fault, maybe I could fix it. This line of thinking was also self-destructive. There were days I was so furious at my trembling ankles, jumpy vision, and swimming head that I’d yell at myself or even slap myself. Other days, I’d dig my nails into my arm until it hurt, marking my flesh with finger-shaped bruises. I’d variously punish myself with nausea-inducing exercise and spend long days in bed. Some days, I didn’t want to get up anymore.

But I did get up, and so does Nightcrawler. But he doesn’t do it alone. He gets up because Kitty helps him, phasing him through the heap of robots, hands scooped under his limp arms. Because of her own faulty powers, she can’t properly hug him. Yet she needs to be broken to save him. Kitty disables the computer that disables the robots because she’s disabled, too; her body fries the circuits because she can’t stop herself from phasing. In the context of the larger story, it’s additionally implied that Kitty saves Kurt because she understands what he’s going through. In X-Men vs. Fantastic Four (1987), also written by Claremont, a ghostly Kitty nearly lets herself dissolve, fantasizing about losing herself in the sunrise. She stays because Franklin Richards needs her. Just like Kurt needs her. Just like Kitty needs him. When Kitty yells at Kurt after saving him, she does so, in part, because she’s scared. She’s also partly yelling at herself. Kurt does the same thing with Brian, lecturing him about how to be a hero while really lecturing himself about all the stuff he used to believe and why he doesn’t believe it anymore. Except he does believe it, because in admitting he wants to die, he finds a reason to live. And that reason is family. That means Kitty and the new family he’ll build with Excalibur. It also means his memory of what the X-Men fought for, stuff like truth, and justice, and the right to exist when you’re different.

You can’t “cure” yourself or other people by yelling at them. That’s not the point of this story. The characters in The Sword is Drawn don’t respond to disability, trauma, and grief in good ways. They respond in believable ways, and in ways rooted in love. It’s also important that none of them are cured, in this story or the next one or the one after that. After The Sword is Drawn, Kitty and Kurt will keep hurting and struggling and finding new ways to be heroes. They’ll eventually get their powers back, but it will take dozens of issues and follow Claremont’s departure from Marvel. The Sword is Drawn isn’t a story about getting over trauma, grief, or disability. It’s about getting used to it, accepting it’s part of you and that you’re still you despite it. And it’s not about getting better. It’s about getting up, and finding a reason to get up, and how that’s sometimes really hard, regardless of who you are or what you do for a living or how many times you’ve saved the world.

Excalibur is often remembered for its humor, and rightly so. The Sword is Drawn isn’t as funny as the ongoing series that follows, but it has its moments, and amid all his grief, so does Nightcrawler. He’s the only character who properly quips in this comic, but when he does, it’s borne of desperation, like during a climactic fight with the Technet that he knows he’s destined to lose. (Unless he gets help, which, once again, he does.) For me, that’s the deeper meaning of both Excalibur’s humor and Nightcrawler’s. In both cases, humor is another means of survival, as well as another form of acceptance. When you’re grieving, it’s not just hard to feel joy; sometimes, it’s hard to feel like you deserve joy. The Sword is Drawn is about that, too—about rediscovering joy and remembering that you deserve it. Which is another way of saying it’s about why superhero comics matter. Even when they’re serious, these brightly colored romps are often silly, but I need them. I need them because they’re silly. Because sometimes, silliness isn’t silly at all.

Fittingly, it’s Rachel Summers, one of the most traumatized mutants, who hails from a genocidal dystopia where she’s brainwashed into killing her friends and family, who gives the hopeful speech at the end, proposing a new team united by loss and driven by the grief informing love. The courage it takes for Rachel, of all people, to hope for a better, brighter, sillier tomorrow, inspires a shamelessly sincere group hug that ought to be the envy of every gritty deconstruction saying superheroes are always ultimately bad for us. There’s value in exploring what’s bad about superheroes. As a scholar, I do that a lot. But as a fan, I’m more drawn to stories that are brave enough to find good reasons to love them.

These days, my vestibular neuritis symptoms are more manageable. But they’re always there. I still limit my driving and there are times when my head feels detached, like it’s numb and floating above me. And if I’m tired or stressed, or if I stare at something too long, my vision occasionally “slips.” It used to feel like I was falling. Now it feels more like the world is falling but at least I know where I am. It’s not the best, but I’m okay. I’m here and I’m glad and I usually get up in the morning.

Literally or figuratively—we’ve all fallen down. Some of us have real-life friends, family, and heroes to catch us, and that’s a beautiful thing. When we don’t, we have comics, including ones starring walking-wounded superheroes who fight for joy and laugh through their tears. In other words, we have The Sword is Drawn.

Between the time I started writing this essay and the time I finished it, my mother passed away. I’m not ready to write about it. (I may never be ready to write about it.) But I probably did anyway. If she could read this, my mother would, as usual, shake her head at my creative punctuation and extravagant adjectives. But that won’t stop me from dedicating this essay to her. Thank you, mom—for more than I could ever hope to name.

Anna Peppard

Anna is a Ph.D.-haver who writes and talks a lot about representations of gender and sexuality in pop culture, for academic books and journals and places like Shelfdust, The Middle Spaces and The Walrus. She’s the editor of the award-winning anthology Supersex: Sexuality, Fantasy, and the Superhero and co-hosted the podcasts Three Panel Contrast and Oh Gosh, Oh Golly, Oh Wow! Follow her @annapeppard.bsky.social.