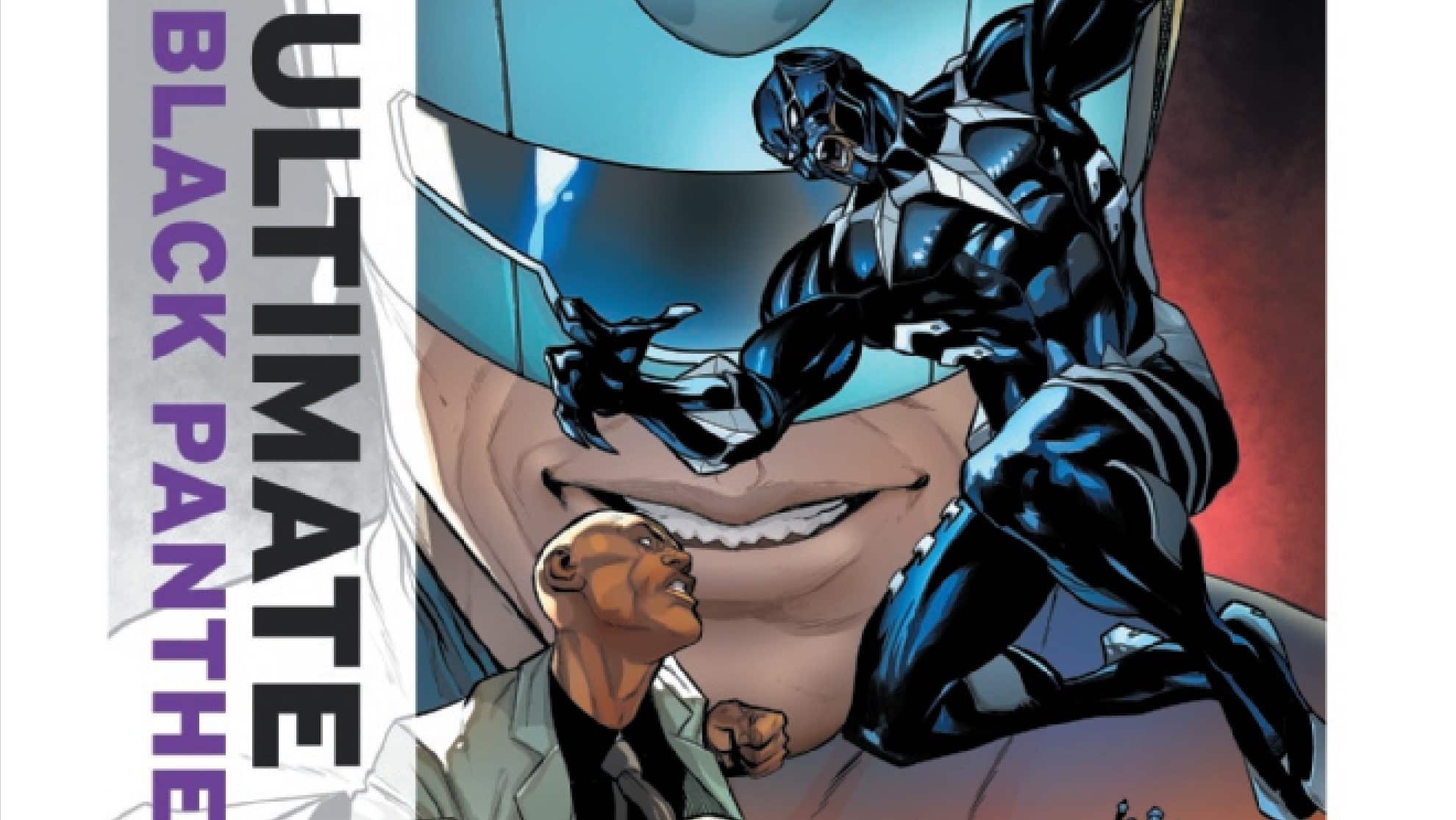

Who is the mysterious Beisa? Delve deeper into Wakanda as we, and T’Challa, have never seen her, in Black Panther #2, written by Eve Ewing, drawn by Chris Allen, inked by Craig Yeung, colored by Jesus Aburtov and lettered by Joe Sabino.

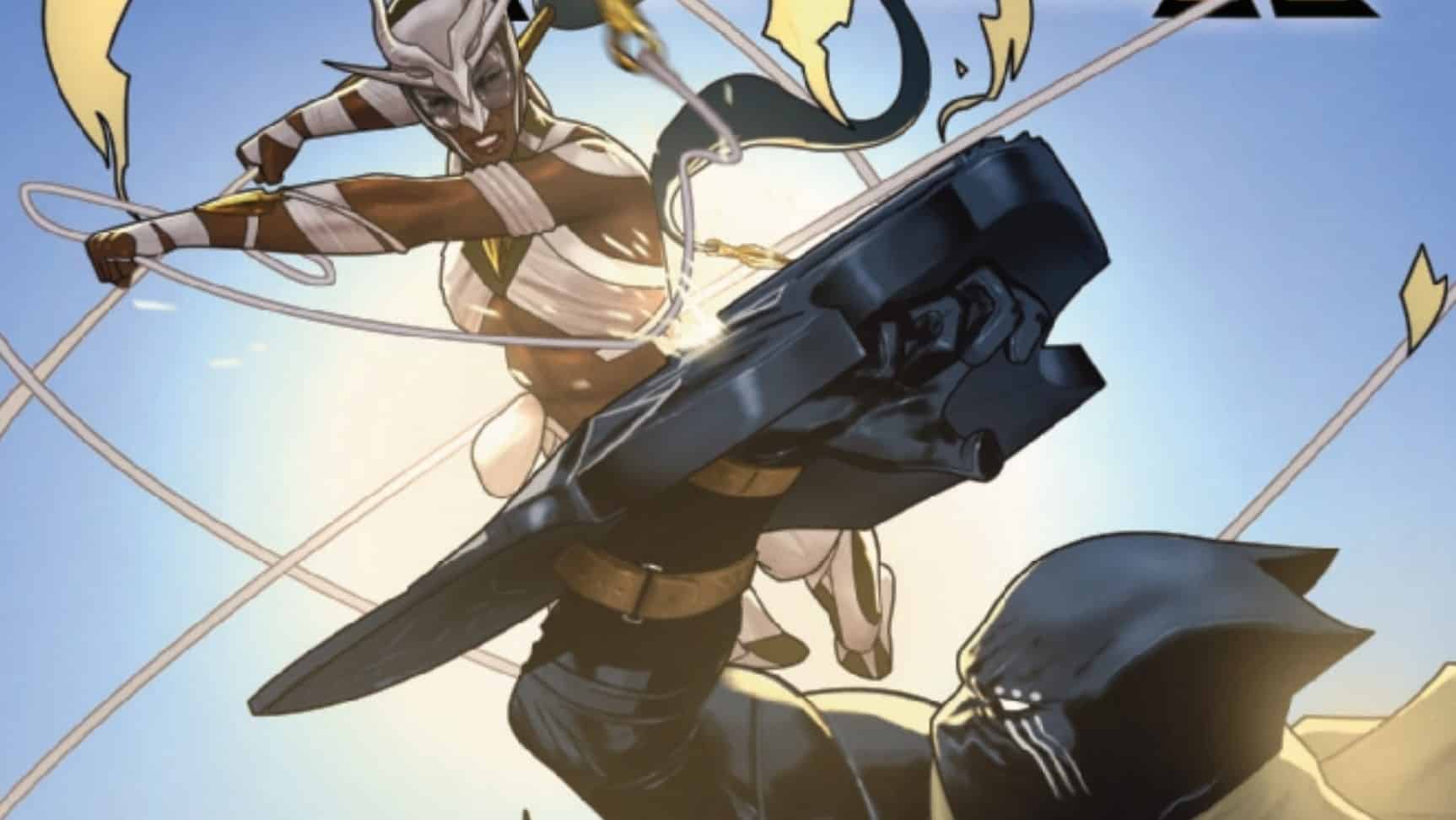

She arrives, shrouded in moonlight, white colored tights covering her svelte, slender figure. She ruminates — rationalizes — that her soon-to-be crimes are really acts of revenge: attacks against the haves for accumulating “endless treasures” in a land where some only merely get by.

How is that fair? How is that right?

She sneaks past their gaudiness, through the window alarms she meticulously disarmed a week prior. The job should be quick. Simple.

But, just as with the distribution of wealth, what should be rarely is.

She is confronted by a crusader in a torn cape. He claims to be a protector of the people; yet who is he protecting? Who is he beholden to? The known and wealthy, or the people?

The hypocrisy is suffocating.

They tussle. They banter. They fall. Hard.

She’s incapacitated and cuffed. He disappears into the night.

She follows, quickly, easily avoiding her would-be captors, escaping back into the moonlight that birthed her.

*****

The above could easily be about a certain Dark Knight and his, uh, “catty” consort. But it’s not: It’s Black Panther #2, and while it is very familiar, it should be said: Familiar is sometimes very good.

It is not unusual for heroes and their antagonists to share a connection; this, of course, makes for good drama. Two sides of the same coin, two divergent perspectives on how to achieve the same goal. It’s less unusual for these antagonists to have an attraction to each other. What makes these interactions work, however, is not simply the divergent viewpoints, or the easily understood drama. It’s not the setup, not the banter or the interactions. No, what makes these characters work together — if they work together — is what they do while they’re apart. These characters need well-established personalities, motivations, desires and moral codes outside of their interactions. We need to know these people well, intimately, before we can decide if they work together.

So then, the question that will likely define this iteration of Black Panther, and certainly this issue, the second in Dr. Eve Ewing’s run:

Who are these people?

The question may seem like a jest when it comes to T’Challa: He’s the namesake of the comic after all, with years of experience behind him. And yet! The previous run did a lot (A LOT) to deconstruct the benevolent, if a bit prideful leader into a visage many could not connect to. Ewing, then, must reconstruct *who* the Panther is while assembling a pantheon of personalities for him to interact with.

And to her credit, with T’Challa, she’s doing an excellent job.

Issue #1 spent the bulk of its time in T’Challa’s head, sussing out his frustration and his frailty in a newly democratic Wakanda. Here, as we spent so much time understanding where he was and how he thinks (hesitantly, world-wearily, but with intelligence and empathy), we see him further suss out his personality … and that of his alter ego. He’s operating under the guise of a line-order cook, using the cover to not only allow him to operate out of sight but to better (maybe finally) understand the plight of the common Wakandan. Remember, T’Challa, unlike so many other superheroes, has generally operated in the light: People knew who the Panther was and what he was capable of. And while this has its benefits, it comes at the expense of really, really knowing the people you’re supposed to protect. This trope is usually why we see other heroes take on secret identities, so they can better identify with the common person. In some cases, these disguises feel disingenuous at best and insulting at worst; yet here, with his empathy and acknowledgement that he doesn’t know his people, that he needs to know his people at the forefront, this secret identity feels necessary and earned.

Less necessary and earned, however, is the issue’s digression into Deathlok. The cybernetic zombie has a long history as political commentary (and sometimes cannon fodder) in Marvel lore. Here we see a Wakandan family use the technology of foreigners to wage some kind of war against a rival (rich) family. Is this wise? Of course not. Will this turn out badly for all involved? Almost certainly. And here is the critique of the non-T’Challa characters here: Their “why,” their ration-de-etre, is not well established enough to allow them to do silly comic-book things without a bit of an eye roll. The rivalry isn’t well established; the personalities of the family members are not super strong; the plight of the Deathlok is only understood through painful yells. And while the last point is certainly fine — we are clearly meant to understand that this character is an unwilling party to these crimes against people and nature — I still argue that a bit more understanding of the “why” would be beneficial to all.

However, one gets the feeling that the bulk of the development will — and should — go to T’Challa’s initial foil, the aptly named Beisa. We’ve established her motivations in the beginning of the issue, self-righteously stealing from the rich in the beginning, and selling secrets as we reconnect with her. And yet these motivations are mildly subverted at the end: She, like T’Challa, like Wakanda, is searching for something. A person, a reason, a motivation, an inspiration.

Will this be enough to endear her to the plight of the Panther? Maybe, maybe not.

But it is enough to endear her to the reader, and that is a change I’m happy has been brought to (moon)light.

A proud New Orleanian living in the District of Columbia, Jude Jones is a professional thinker, amateur photographer, burgeoning runner and lover of Black culture, love and life. Magneto and Cyclops (and Killmonger) were right. Learn more about Jude at SaintJudeJones.com.