Welcome back to our three-part look back at the Grant Morrison — and Frank Quitely and John Paul Leon and Phil Jimenez and others — run of New X-Men! From the first arcs — “E Is for Extinction” and its successors, dealing with Cassandra Nova — we’ve seen how Quitely’s designs and Morrison’s scripts focus on mutants whom readers would not want to be: They’re grotesque, or obnoxious, or beaten down, or (like Beak) motivated by self-hate and shame. Those less attractive and less famous mutants come together, not just at the Xavier Institute, but in the community, somewhere in Lower Manhattan, called Mutant Town: “the dawning of a future,” as Morrison put it in their book Supergods, “with new music, new dreams, new ways to see and live,” “representatives of an inevitable next stage of evolution.”

The run also shows bad behavior from adult mutants we might otherwise trust. Hank McCoy breaks up with his girlfriend by claiming to be gay. Charles Xavier is a jerk (but he was always a jerk). Scott Summers isn’t getting along with his wife, when they were supposedly the perfect couple. He’s seeking therapy from Emma Frost, who’s always at risk of turning back into a villain. Normally benevolent characters usually see plans backfire: Morrison’s characters may try to save the world, but they should not have, or seek, power over other people — it’s an ethics, if not a politics, of anarchism, where hierarchies ought to collapse, set against the “confrontational paramilitarism” (Morrison again) of other super-teams.

The only adult who speaks in easy-to-follow moral terms—terms that would fit well into God Loves Man Kills — is the peaceful, compassionate, stunningly powerful masked mutant Xorn, who says things like “No one should suffer in chains as I did.” In New X-Men #127, he ventures into Mutant Town to rescue, if he can, the most grotesque mutant we’ve seen, an enormous beetle-like child whom only his mother can love: “He’s just my son.” She’s tried to kill him, and herself, out of misplaced pity, but Xorn’s determined to save them: “He will not be alone in this new world.” Cops kill him anyway. It’s literally a dark story, full of blacks and browns and broody Bill Sienkiewicz inks, and it’s the Bad Ending to a very familiar story of coming out into a world that hates and fears you.

It’s also the first in a series of genre experiments. Superheroes, for Morrison, aren’t a kind of story; they’re a kind of character around whom Morrison can run up genre flags and see who salutes. First, the urban noir where no one wins. Then the over-the-top super-spy drama in a European capital. Fantomex — whose name X-ifies the French literary supercriminal Fantomas — says things like “I’ve always managed to stay under the radar, stealing a Van Gogh here, a priceless alien artifact there.” No one (certainly not Fantomex himself) can take him seriously, even as the body count mounts around him. Almost the first time we meet him we see him pour water over his head, as if to say “Calm down, it’s just a story.” The same story lets Igor Kordey and Dave McCaig draw tropey zombie horror: red fading to black, terrified mobs, the shout of “Don’t let them touch you!” — another genre checked off.

By contrast, the Scott and Emma drama — the emotional center of mid-period New X-Men — begins in a restrained, nearly black-and-white, half-lit eight-panel grid. Scott and Jean have been trying to keep up “this teenage unconditional love in the face of unstoppable chaos and change,” but he can’t do it, and he needs somebody to listen: “I’m not who I was and I can’t seem to tell her who I am, in case she hates what I’ve become.” Honestly I have no clue in the world how those panels must read to cis people. Nor do I understand how Scott and Emma would feel, today, to anyone who’s never made a close friend, or begun a romance, online, or fallen into a relationship that grew far closer than anyone could plan.

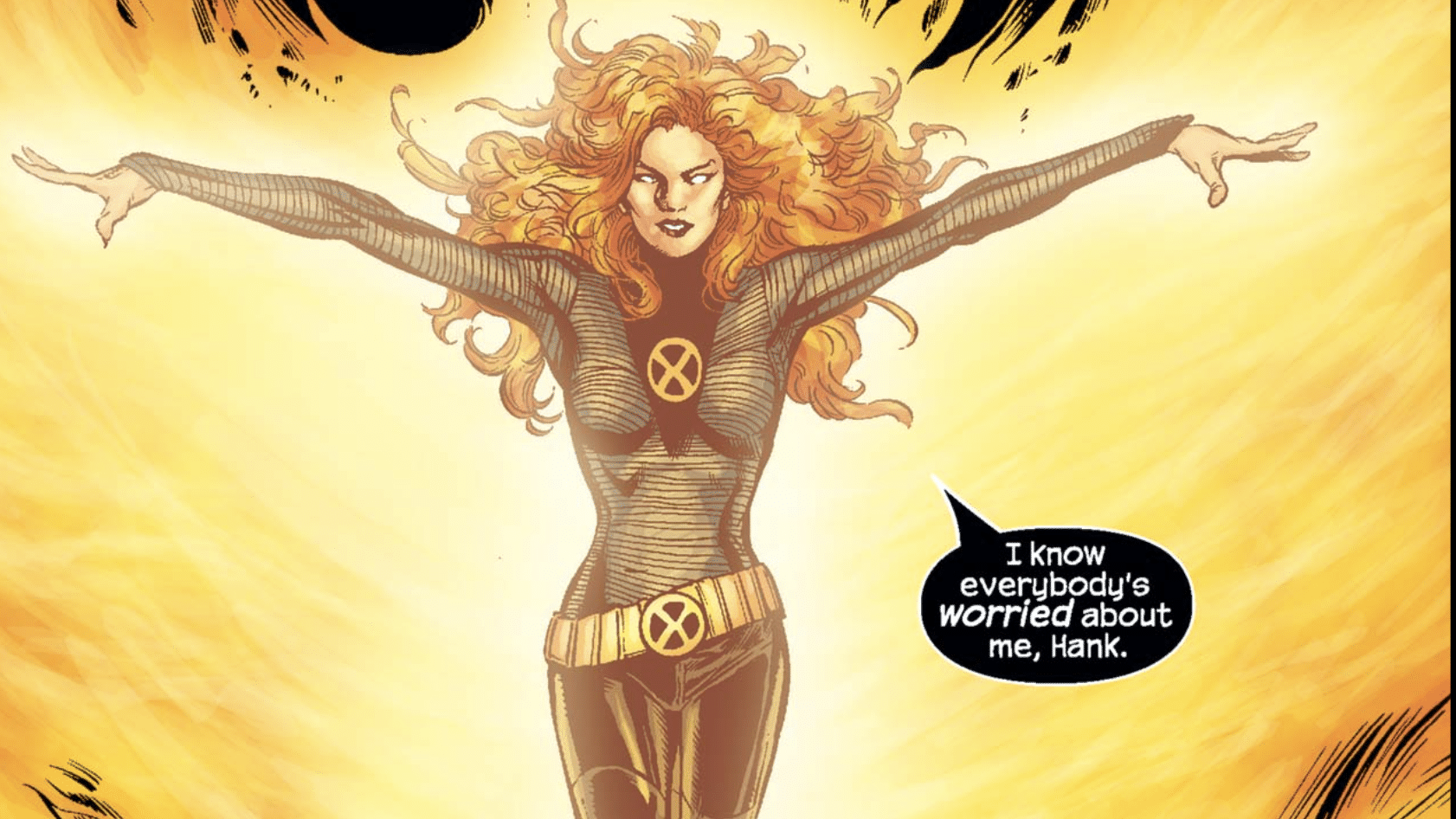

Scott-Emma-Jean would become the series’ A-plot. But not yet: It’s on the back burner during the Fantomex arc, which also mocks the military-industrial-tactical mindset that other comics, and games and films, nourish: “I’m a highly trained death machine with no human feelings! Sir!” says Corporal Animal, before Jean rewrites his brain. The soldiers and the X-Men are fighting “an extinction sequence,” a version of “artificial evolution,” whose propaganda has led other Morrison fans to believe the whole series advocates direction to evolution, saying we ought to move it along. The series does posit a coming human extinction, but Morrison never considers that morally good: His writing stands instead with Charles Darwin, and with the great Richard Lewontin. Evolution by means of natural selection keeps happening, but it does not have a built-in moral valence: We can observe it and then try to follow our individual moral codes.

If we can. Menaces in Morrison’s run — none of them biologically inevitable — exceed or defy individual agency: They are infectious agents who take over other minds, or toxic clouds, or distributed means of possession (like Cassandra Nova) or “bacterial consciousness,” like Weapon XII, Zona, who “turns his enemies into himself.” To that list of distributed intelligences we can add hundreds of Jamie Madrox dupes, in France, and then the ghostly voices that haunt Genosha, via magnetic traces in Polaris: “They’re inside her … millions inside her … Her consciousness is bursting open.” Marvel newcomer Chris Chuckry’s colors burst open, too: Great swirls of green and slabs of violet gray extend around a statue of Magneto, rising from the Genoshan ruins like a grim 9/11 memorial, carrying — as the scholar Julian Darius has explained — that era’s sense of “unfathomable sadness.” It’s moving, rather than heroic, and it shows how the dead stay dead.

More direct, less effective reminders of 9/11 introduce Marvel’s first mutant to wear an abaya, Sooraya Qadir, aka Dust. A hijacker speaks “Pakistani,” which isn’t a language. Feral reads “The Hindu Times,” which is an Oasis single but not a newspaper. Sooraya’s still waiting for a Marvel writer able to get her point of view: Her debut reflects its own time, and its own (as far as I know) white creative team (for a more informed take on the character, try Khaliden Nas’ episode of Cerebro. Sooraya, too, represents a collective, a way to be less than and more than one human being, not because she stands (unfortunately) for a religion and an ethnicity, but because she turns into clouds of sand.

Next up is Morrison’s version of a story about school rebels, nerds vs. cool kids. People who don’t like the X-Men sometimes say the mutant metaphor invites nerdy, cisgender, nondisabled, straight white boys to call themselves oppressed. I’d argue it invites them to look for oppression instead, but what if the haters were right? The X-Men would look like Quentin Quire’s school gang, seeing themselves as history’s and evolution’s morally righteous side, out for publicity and revenge (but really to impress girls). Is the Morrison run a gaudy, satirical take on the mutant metaphor, or just a way to use it differently? By the time of “Riot at Xavier’s” — no. 14 on the official authoritative list of best X-tales — we still do not know.

We do know that Quentin’s awful. Every time he says something that sounds like a coming-out story (“Have you any idea what happens inside when you find out you’re not the person you thought you were?”), he follows up with something mean (“Who wants to see Slick naked?”). Worse, “he’s able to influence minds around him,” as Xavier warns. Also he’s on Kick, which will turn out to be yet one more instance of anti-individualism in Morrison’s run, one more sign — along with the Cuckoos and Dust and the divided consciousness of Cassandra Nova and the infectious mind of Weapon XII and the mysterious disembodied mentalities of Martha Johansson and/or No-Girl and Dummy, “an intelligent gas in a suit” — that we do not make choices wholly on our own.

Like all of Morrison’s villains, Quentin and his gang think evolution has a direction and they ought to move it along, because they are higher forms of life. “We’re the next generation, like on TV. The improved version,” Quentin tells his gang, his back to the viewer. Xorn appears to know better — he gives inspirational speeches: “I was bound in darkness but I never lost the freedom to dream,” he tells his special class on a special hike through special greenery outside the school: It’s all a bit after-school special. If there’s a credible moral center, it’s Logan, who — in a spectacular white-on-blue telepathic classroom, blackboard doodles all around him — gives the best advice for teachers and parents that an X-book ever proffered: “Contain the damage,” “wait till they grow out of it,” “don’t act like a jerk,” “people don’t change much from one generation to the next. … They got habits, same as every other beast ever lived.” It’s Logan who stands against projects of new school discipline, as well as against Quentin’s, and the U-Men’s, idea that humans and mutants can be violently and willfully improved.

There’s a riot coming up. But not yet. First, Frank Quitely and Chris Chuckry give us another genre piece, an entire issue colored in darkness, blues and blacks and deep shadows everywhere as the special class goes out at night. While we, as readers, get lost in Chuckry’s shade, Morrison has been setting up a confrontation, knocking Professor X out and letting Quentin spout familiar rhetoric, the sort we might have seen from the 1990s-vintage Mutant Liberation Front: “Your rhetoric about man/mutant brotherhood sounded really inspiring when I was thirteen, Professor, but I grew up. … Your ‘dream’ has failed.”

What’s new about Quentin lies not in his ideas but in the way he manipulates his peers, and in his look, half Nazi skinhead, half school prefect. It’s the most British part of this Scottish writer’s performance. “Riot at Xavier’s” echoes — as they have said — the famous British film if… (1968), about a rebellion in a fancy school, starring a pre-Clockwork Orange Malcolm McDowell. Quentin’s resemblance to a U.S. school shooter is not quite an accident, but it’s not quite the point: He says, or pretends, that he’s leading a generational uprising against a tottering aristocracy on behalf of militant youth, and — like everyone in the Morrison run who believes in inevitable revolution, a superior class and a direction for evolution — he proves dangerous and wrong. He also turns his supposed friend Glob Herman into (so Glob shouts) “a suicide bomb.”

Of course the adults can’t stop him. Kids have to do that, kids who aspire to glamor and safety more than they aspire to heroic examples: “Riot at Xavier’s” combines great fight scenes with real sadness and real stakes, and shows, not that nothing must change (Morrison is no centrist), but that vague aspirations to revolution, backed by grievance and indifferent to suffering, get hopes crushed and people killed. Again, Logan — no friend of institutions — delivers Morrison’s verdict, such as it is: If the Omega Gang wants to do some good, they should emulate not the Red Guard but the Peace Corps. “That’s where you’ll get to put all that revolutionary energy to good use,” in “the third world,” “helpin’ people who need it.” (If, like some ex-Peace Corps people, you’re wary of white saviors, try imagining Glob, Slick and the others putting up solar panels in the Dakotas.)

I’ve been neglecting Scott and Emma so I could give them full attention now. New X-Men #131 is, as Xavier says, a “shared telepathic experience,” taking place partly inside Scott Summers’ head, where — of course — he’s always replaying a plane crash and asking if he is or should be in charge. “It’s like everyone’s watching me. Like I’m doing something wrong.” You’re not crying, Scott, I’m crying. He can’t figure out if he’s out of control, or violating a moral code, or doing what he has to do to get out of the emotional trap of his monogamous marriage to — as Emma says — “a human furnace of violent emotions.” Is Emma an ethical therapist? Of course not. If you were Scott, what would you do?

What if you were Emma? Her apparent failure after the riot, as her student creme de la creme reject her, copies the famous Scottish novel and film The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, where the crypto-fascist teacher’s downfall demonstrates human hubris and frailty. In New X-Men #137-138, it’s a lesson about power: Neither angry youth nor authoritative adults can be trusted to exercise it. Poor Emma, “searching for a new project,” as she tells Angel. Poor Cuckoos. Poor us. Even poor Quentin, who speaks the first truth of his life, from an isolation tank, to Xavier: “What if we were both wrong?”

What if everything’s wrong? What if we can imagine a way to live without exercising live-or-die, shame-or-glory, you-owe-me-everything power over other people, even the ones we love? How would that feel? It might feel like the inside of a volatile Emma Frost’s head, as seen by a terrified, vulnerable Scott Summers. “These dark feelings in your head are just ordinary human emotions,” Emma tells Scott, and she might lose her (nonexistent) counseling license, but she’s right: “Stop trying to live up to such ridiculous, restrictive ideals.” Stop trying to be a superhero. He answers — and again, I’m crushed; I’m slain — “I’ve never been allowed to be anything else.”

Yes, Emma’s a self-interested drama queen. Check out the Warhol-style portraits of herself in her office. But Jean — who has social convention on her side — has been very much like an abusive partner: Scott, and Professor X, and everyone else, have lived in fear of her. Charles tells Scott that “we cannot risk” making Jean angry. Take a moment, please, to think about real world situations where that’s what you’d say.

Scott hasn’t even slept with Emma: “It’s Jean or nothing,” he says, half-naked in a psychically projected bed, as he backs away from her. But Jean doesn’t care: “They were thinking about it the whole time.” Why does Jean care so much? Blame mononormativity. Or blame Jean’s wish to be in control. (“It’s true. I have the worst temper,” she later admits.) Or blame the Phoenix Force that seems to have infiltrated her own emotions: As with Quentin on Kick, and Weapon XII, and Cassandra Nova, Morrison may not want us to think of their characters as wholly autonomous agents. Morrison does, however, get us — at least he gets me — in Scott’s shoes, and on Emma’s side, before Emma gets (very literally) broken up into a million transparent pieces.

Then Morrison switches genres again. Having done super-spies, school riots, camping trips, Orientalist combat reportage, adults’ adultery and (I’d argue) emotional abuse, Morrison, Phil Jimenez and their colleagues set up a classic locked-room mystery, bringing in detectives new to the scene: Bishop and Sage, who had been hanging out in Claremont, Kordey and Larroca’s X-Treme X-Men. As in the best locked rooms, everyone has a motive, even the detectives: “Emma Frost,” Bishop admits, “was one of our least favorite people.” Moreover, “in a world of mindreaders, shapechangers and disembodied consciousness,” individual guilt might not be a thing.

Indeed, we’ll discover that no single individual committed this crime: One took the blame, one held the gun, one mind-controlled the gun-holder and someone (but who?) mind-controlled the mind-controller. Beak and Angel complement the locked-room mystery with a sympathetic focus on teen pregnancy, another genre explored, five years before the movie Juno, with Beak — who certainly does not want to move evolution along, or take over the world, or get anything except a bit of acceptance — settling back in as the only credible candidate for a reader surrogate. Jimenez, Chuckry and inker Andy Lanning, having concentrated on small panels and intricate story, go to town on a full-page spread of new mom Angel with her flying babies. Then there’s the half-page of Phoenix flare, and the shiny, flashy, sudden reconstruction of Emma Frost, who wakes up — having been put back together, Osiris-style — screaming “Esme!” as Phoenix flames recede. But it wasn’t exactly, or wholly, Esme either: The mystery rolls on toward the climax of Morrison’s run, which is also the arc where Morrison — to judge by their later interviews — lost control, until New X-Men became “more like a prison than a playground.” Why and how? Find out next time.

Disclaimer: As an Amazon Associate, ComicsXF may earn from qualifying purchases.

Stephanie Burt is Professor of English at Harvard. Her podcast about superhero role playing games is Team-Up Moves, with Fiona Hopkins; her latest book of poems is We Are Mermaids. Her nose still hurts from that thing with the gate.