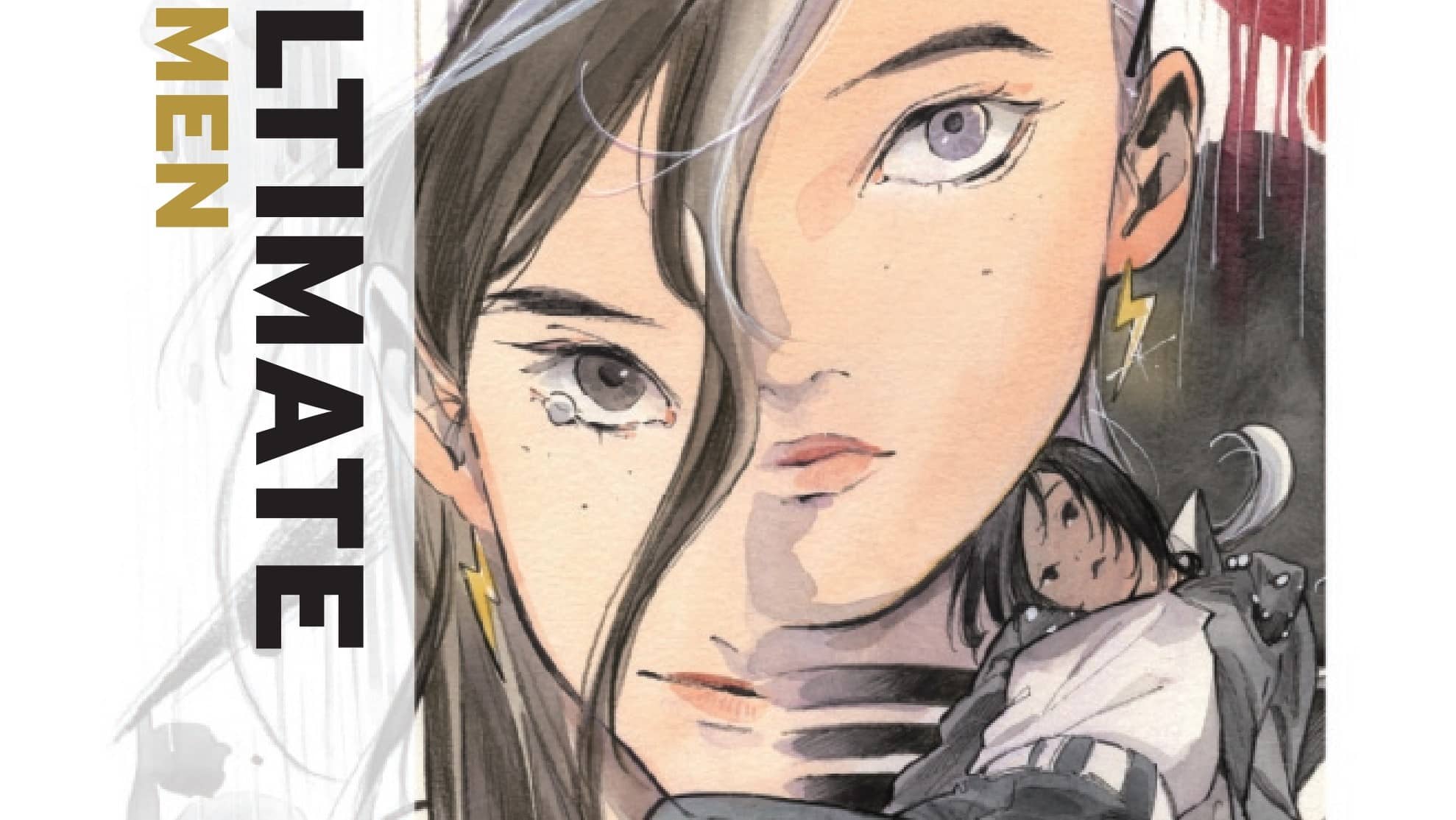

Mei Igarashi was a regular girl until she discovered her unusual abilities and her hair changed from brown to white. Now, learn how and why she came to idolize a mysterious freedom fighter in Africa who also harnesses the power of the storm. Ultimate X-Men #3 is written and illustrated by Peach Momoko, with script adaptation by Zack Davisson and letters by Travis Lanham.

Content warning: domestic violence, child abuse.

For the third installment in her mutant universe revolution, Peach Momoko pares back the magic for a dose of realism in the series’ darkest issue yet. This is the origin story for Mei Igarashi, aka Maystorm, one that takes an indirect approach to dealing with the difficult subject matter of domestic violence to varying degrees of success.

The issue begins with a flashback to Hisako Ichiki, aka Armor, playing a game of Kokkuri-san, a spirit board game involving a 10-yen coin, with a friend. Conspicuous in the scene is a young man with glasses who participates silently. The game ends before the girls realize that neither had invited him. Flash-forward two years to Hisako finding a 10-yen coin lying at her feet.

This is presumably a mystery for another time because the issue soon shifts to Mei’s origin. Having recently moved into a new house, Mei is encouraged by her mother to introduce herself to their neighbour. After school that day, Mei calls at the house only to be accosted by a sad-looking cat painted in ritualistic-looking symbols. The reclusive neighbor eventually answers the door and lunges toward Mei to grab the cat. She freaks out. So does the cat. It scratches her, leaving a nasty gash on her arm.

She returns home to rest, the cut ostensibly an outlet for both her powers and the shadowy figure that Hisako dreamed was under her skin. She is interrupted by her rowing parents, an exchange that escalates rapidly into violence and results in Mei being struck by her father. This proves to be the inciting incident for Mei’s weather powers to fully manifest, resulting in the house being blown apart. Mei’s father, cold and emotionless, kicks her out of the house.

The present snaps back into view like a volleyball to the face, as we are introduced to Mei and Hisako’s peer Nico Minoru (of Runaways fame). Without warning, she reveals both her own and Mei and Hisako’s mutant identities for the first time.

The lightning in the dark

The Gurokawa (“creepy cute”) tone of the series so far has seen the youthful innocence of its antagonists invaded by very adult themes of depression and suicide, and the exploration of Maystorm’s origin story in this issue is no exception. Domestic abuse is a subject that has historically not been handled well in superhero comics. Many such examples of domestic violence have been written by male writers and have an element of spectacle to them framed through the male gaze. Where Hank Pym hitting The Wasp or Reed Richards striking Sue Storm are played for dramatic effect, examples in X-Men include Skids and Boom Boom developing powers in response to abuse, providing them protection from future violence. While fairly progressive for their time, both characters’ stories are somewhat defined by their abusive relationships. All of this is to say that the treatment of the effect is as important as the cause and that, given the history, a single issue of a superhero comic achieving this level of nuance is a big ask.

Momoko’s takes this on to mixed results. While she de-emphasizes the sense of spectacle and centers victim over abuser, it’s worth noting that the outcome could have been achieved in different ways. The tentativeness with which it is dealt in this issue dampens the emotional impact of the scene, but it’s clear that Momoko is more concerned with Mei’s journey after the event. The use of metaphor and subtext centers Mei’s experiences in a delicate and uplifting way, which rewards the reader for treating the subject matter with the sensitivity that the story does.

In terms of the scene itself, the dispassion of Mei’s father throughout is striking, and it’s clear that Momoko is engaging with a different paternal figure archetype than the often sensationalized out-of-control anger you typically see in scenes like this. After not saying a word in the scene until after he has struck Mei, causing her powers to manifest, the choice of the verb “need” in “I don’t need punks like you in my house” is curious. It implies that the inconvenience of an out-of-control mutant is more pertinent than any prejudice he holds. Combined with the clearly reciprocated emotional distance between the two, exemplified by Mei encouraging her mother to “leave him,” it’s clear that love was lost some time ago. This de-centers the abuser and therefore ensures that the pathos in the scene is reserved for Mei and her mother.

The grey, brown and beige color palette sharply contrasts with the effervescence of Momoko’s typical style and is used to emphasize both the mundanity of Mei’s existence pre-powers and the darkness pervading the scene. The coldness of the dialogue and the drabness of the scene both feel intentional, but their combined effect is to make the scene feel a little flat.

The reader doesn’t see the aftereffects of the scene on Mei, which is a strong editorial statement in and of itself. It leaves the reader to piece together through subtext Mei’s journey to becoming the precocious teen we first met in issue #2, which is more effective. The change of hair color from brown to white after her powers kick in signifies her breaking free from her humdrum existence to a life of magical heroism. It is also both a long-lasting symbol of her trauma and a source of strength. The fact that she draws strength from her connection to mutantkind’s strongest figurehead in this nascent universe is a powerful testament to the strength of the found-family metaphor as applied to X-Men.

Early on in the issue, we see Mei reading news of Storm’s public emergence on social media, which raises a question about the role of determinism in Maystorm’s powers. Unlike Skids, Mei’s powers are not connected to the source of her trauma but to her source of strength to get through it. The fact that the issue chooses to leave much of this unsaid rather than confronting it head on is undoubtedly a good decision, even if the reason for framing it in this way is not apparent.

The Goth

The end of the issue sees the introduction of a third potential member of our Ultimate X-Men, Nico Minoru, which is a significant variation from the character’s Earth-616 counterpart. In mainline continuity, Nico is the daughter of two dark wizards and is herself a dark magic user. Here, she is the daughter of two psychics and looks set to be a formidable mutant who will be crucial to the X-Men of Earth-6160. While the presence of a Japanese character provides immediate and obvious synergy to the story, it’s understandable if X-fans feel a little short-changed that we’re not seeing Momoko’s take on the classic mutants.

The bigger issue here is the unevenness of the issue’s pacing, which exemplifies the emerging issue with the series in general. Frankly, not a lot happens in this issue. The majority of the scenes are in flashback, which, while effective in fleshing out the world and its characters further, does little to progress a story that is already moving relatively slowly. This is traditional of Japanese storytelling that eschews prioritizing plot progression in favor of introspection, often returning a character to where they began, having learned or been changed by their experiences. Both issues in this run so far do this. This issue does not, instead favoring a cliffhanger ending that rushes the reveal of Mei and Hisako’s mutant identities without much buildup. While it makes this issue a little uneven, it perhaps signals an acceleration of the plot, which, at least from my rotted attention span’s perspective, is welcome.

The creeping shadow

Momoko deepens the mystery of the ghost-like figure who is referred to in the issue’s blurb as Shadow through two flashbacks that establish a potential human host and connections to Hisako’s and Mei’s pasts. First seen in issue #2 sat in the closet of the school surrounded by notes bearing the names of the dead, the man with round glasses and a middle-parting haircut seems to be more than he first appeared. When the man answers the door to Mei, he is shrouded in darkness, appearing to be the disembodied shadowy figure who has been hounding Hisako. Subsequent panels soon reveal that the man also bears an uncanny resemblance to the boy at the beginning of the issue. So what’s the connection between the two, and who could he be?

Let’s just follow Occam’s Razor here and consider the name: He’s probably the Shadow King, isn’t he? If that is the case, what does he represent, and how does this apply to Ultimate X-Men?

In his simplest form, the Shadow King is a parasite that latches onto a person in the physical realm. In the 616 continuity, this has typically been Amahl Farouk. Its purpose is to grow and consolidate its power through the negativity in the world, and is therefore motivated to stoke hatred and intolerance. In Ultimate X-Men, we have seen the Shadow prey on guilt and trauma, manifesting itself in a contemporary way in the form of youth depression and anxiety. We’ve now seen both Mei and Hisako targetted by this presence, which suggests that their coming together may be more than coincidence. With the group of friends and fellow mutants expanding, they now have a common enemy; they just don’t know it yet. With more team members set to join over the coming issues, it looks like we’re finally getting our X-Men.

Buy Ultimate X-Men #3 here. (Disclaimer: As an Amazon Associate, ComicsXF may earn from qualifying purchases.)

Dan Grote is the editor and publisher of ComicsXF, having won the site by ritual combat. By day, he’s a newspaper editor, and by night, he’s … also an editor. He co-hosts The ComicsXF Interview Podcast with Matt Lazorwitz. He lives in New Jersey with his wife, two kids and two miniature dachshunds, and his third, fictional son, Peter Paul Winston Wisdom. Follow him @danielpgrote.bsky.social.