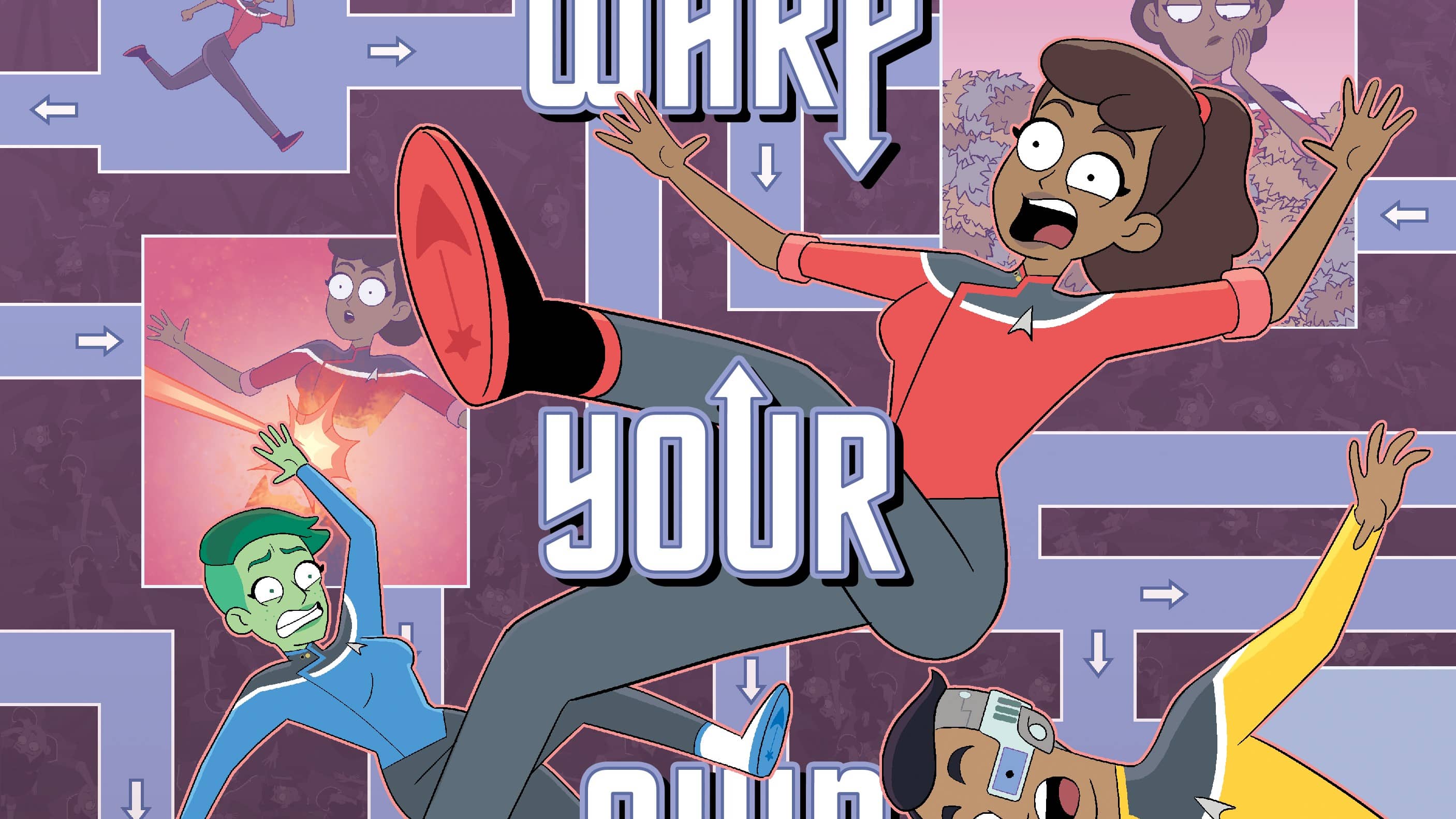

Once again, I’ve reached Ryan Qwantz North as he travels the highways of Canada, ever his constant remote companion, this time to discuss Star Trek, chooseable path stories and Star Trek: Lower Decks — Warp Your Own Way, the upcoming chooseable path graphic novel from IDW, with art by Chris Fenoglio, colors by Charlie Kirchoff and lettering by Jeff Eckleberry.

[The following interview has been edited for length and clarity]

Mark Turetsky: This is your first interview after what Chip Zdarsky described as “The Incident.” For any readers who don’t know, you allegedly mispronounced the name of The Sub-Mariner…

Ryan North: “Nuh-MORE.” I did. I stand by it.

Mark: And Chip Zdarsky called for you to be fired, and created a hashtag, #fireryannorth. I don’t know if you’ve had time to see it, but just hours ago, he issued a tearful apology.

Ryan: I saw.

Mark: And now he’s asking people to hire you and giving out what I can only assume is a fake email address. Being a good researcher, I reached out to it and asked, “Hey Chip, do you have any questions for Ryan?” but he hasn’t gotten back to me.

Ryan: Terrific. [sarcastically] It is an extremely real email address that I definitely control.

Mark: Here’s the thing, I grew up in Montreal. And in Montreal, there is a Metro station called “Namur.” It’s named after a place in Belgium. So when I first heard about Namor, I thought, oh, he’s named after the same thing as the Metro station, except with an “o” instead of a “u.”

Ryan: How did you say it?

Mark: I probably said, “Nuh-MORE.” I mean, it’s French, “Namore!”

Ryan: Namore! Bien sur!

Mark: Do you have any comment to make, now that you’re breaking your silence about this issue?

Ryan: I’m glad that Chip’s apologized. I didn’t think he had to cry quite so much, but I appreciated it. And I also appreciated how he called me “a competent writer.” And I really hope that the call he put out for people to hire me, for exposure, to work for free, I think that might get me somewhere, so thank you, Chip!

Mark: What’s important is that it’s got people talking about Namor.

Switching gears a little bit, you’ve written the two Shakespeare chooseable path books, To Be Or Not To Be and Romeo And/Or Juliet. You also did a chooseable path issue of Squirrel Girl. And now you have the forthcoming Star Trek: Lower Decks — Warp Your Own Way. Have you found that writing chooseable path stories has affected your comic writing, especially in sci-fi? Because there’s something to be said for them being related to time loop stories, which you’ve also done.

Ryan: Yeah, that’s interesting. I can tell you my process of writing a nonlinear story like that. I developed it while working on the Shakespeare books, it was just to start writing until you’ve reached a natural inflection point. Someplace where the characters make a choice, and then stop and ask yourself, “what are the two or three coolest things that can happen here?” and then write them and continue along that way. And when I’m writing a linear story, it’s kind of the same process. You’re always asking yourself, “what’s the coolest thing that could happen here?” and you’re trying to tell the best story that you can.

The advantage of a nonlinear narrative is that you do your top four or five options, and then narrow it down to two or three. But either way, you’re still telling a story. Not to get too far into theory, but the phrase “choose your own adventure” or “chooseable path adventure,” they’re lies, because you’re always choosing something from a set of adventures that are pre-chosen for you.

And so when I’m doing a nonlinear narrative, I’m always thinking of the metanarrative, because I assume people are going to read the book more than once. And what’s the kind of story you’re telling across the entire book? Because that’s also a story that says something about the universe that the character and the reader is playing in. There’s a lot of cool theory for this type of storytelling that I don’t think a lot has been written about, and I hope someone does, because it’s great, and it’s really cool and it’s another tool in your toolbox as a writer.

Mark: It’s kind of a cliché with writers of fiction that , “oh, well, I wanted it to go a certain way, but my characters had a different idea, and they took it somewhere else.” Do you find that happening?

Ryan: Kind of the opposite actually. I have had the experience of writing something and it doesn’t work, and I reread it and I say, “this is bad, this isn’t working.” And the reason that it’s not working is that it’s not true to the character. So I have an outline, I write the story according to the outline, and I realize when I get to a certain point in the story that it’s not true to what these characters should be doing. And the answer then is to adjust the outline or throw out the outline, not to change the character, because that’s the harder and least rewarding job.

So it’s not like these characters sit around and talk to me, it’s more that I can feel when I’m pushing against where they would want to go and what they would naturally be doing. And if you’re writing something that feels untrue, it’s going to feel untrue to read it, too. So I’m not one of those writers you talked about, like, “oh, my characters speak to me and they wanted to do this,” but I do respect when I’m trying to get the story to go somewhere it doesn’t want to go. So when that happens, you can’t force it, you have to go back and change something, reevaluate.

Mark: That’s interesting, because when you think about writing in a Shakespeare-adjacent space, the characters have their hamartia, their fatal flaw, to use my fancy drama degree words, so putting them in a chooseable path story, it kind of goes against that whole notion. I mean, both of your books play on tragedies.

Ryan: Well, it does and it doesn’t, right? One of the neat things about interactive media is the way that the player or the reader takes ownership of it. An example I always think of is, if you’re playing a Mario Brothers game, you miss a jump and Mario falls in a pit and dies, you don’t say, “Mario fell in a pit and died,” you say, “oh, I died.” I made that choice. And there’s a bit in Romeo And/Or Juliet, I write, “Romeo is a young man who’s in love with being in love, and he is interested in kissing women. He is a man who wants to kiss a woman.”

Later on, I give you the option of maybe Romeo kisses a man instead, your reaction isn’t “Ryan is a bad writer, because he’s clearly established that Romeo is super-straight, and here he is doing this other stuff.” Your reaction instead is, “oh, my Romeo is going to do this. My guy is going to break the rules.” And so you have this great opportunity when writing nonlinear narrative to do things in this form that you can’t do in a normal classical book. So, for example, the tragic flaw, yes Hamlet has this tragic flaw of indecision, but if in To Be Or Not To Be, you go off and kill the king immediately, your Hamlet doesn’t. You get to explore what it would be like to not be crippled by this tragic flaw, to overcome it. So you’re still in conversation with that tragic flaw, you just get to explore it from different angles.

Mark: The thing with Shakespeare which always kind of gets my goat is that, while most people experience these as books, they’re plays. They’re meant to be put on their feet and explored that way. And this idea of keeping the original text sacred is a fairly recent thing. My wife’s an 18th-Century scholar, and she was telling me that in the intervening years between Shakespeare’s time and now, people made all kinds of changes to their stage productions. Like, for a while, King Lear had a happy ending. Or the ending of Romeo and Juliet changed so that, not that it made it a happy ending, but that Romeo and Juliet could have one last scene together. Where Juliet wakes up after Romeo has taken the poison, but before he dies, so no, that’s not making it a happy ending, it makes it even more tragic, because they can talk to each other about how it’s all gone wrong before one of them dies and the other commits suicide.

Ryan: I love that, and it resonates because one of the things that gets me excited me about writing Romeo and/or Juliet was getting to give them their happy ending they never got. There was this tradition of punching things up (for various directions of “up”) before we got “canonical” versions, and in a way the interactive versions of the plays I did continue that, I guess! I find this FASCINATING.

Mark: How do you think that changes your relationship to the reader?

Ryan: It makes it kind of a conversation. There’s some playfulness to it, absolutely, because you’re choosing your way through this story and I’m the one still telling the story and playing with the choices I’m giving you. For me there’s always a sense of the storyteller almost being a character. In the Shakespeare books, the narrator will sometimes converse with you, take over the story and make choices for you. In Warp Your Own Way, it doesn’t quite reach that level necessarily, but there is this sense of playing with choices and the characters almost in conversation with the reader, because they’re the ones deciding what will happen. It’s a fun kind of liminal space between a normal story and breaking the fourth wall, where you’re engaging with it, but still staying fully within the narrative.

Mark: You’ve got an option in your Shakespeare books where you can play as different player characters, like the Ophelia path or the Nurse minigame. It seems like Lower Decks lends itself to that. Star Trek, with the possible exception of Discovery, doesn’t have a main character but focuses on a core cast.

Ryan: When you read the book, and I’m so excited for you to tell me what you think when you do, there is no choice of character in that you’re playing as Mariner the whole book. But there are several reasons for that. One is, your space in a comic is so much more precious than it is in a prose novel. When I was self-publishing the Shakespeare books initially, I could do a 120,000 word novel and that was fine. But there are certain market restraints that are above my pay grade, that said “we’re not doing a 700 page comic here, Ryan, you have to make it fit within a certain limit.”

Also, by just playing Mariner, you get to focus on her experience through this story. And she and the player are closely aligned, they both want the same thing. So it felt natural for this sort of adventure, to have it just be tied to her. Plus, she’s tons of fun, and she gets to hang out with the other main characters, Boimler and T’Lyn and everyone else, so often in the story that it doesn’t feel like she’s off doing her own thing, it feels like you’re doing a Lower Decks adventure with all of them.

Mark: I know that you tend to work very closely with your artists, for example on Danger and Other Unknown Risks with Erica Henderson, from what you’ve both said, she was very involved in plotting and making big story decisions. Are you afforded the same kind of freedom to collaborate so completely with Chris Fenoglio when you’re dealing with a chooseable path comic, where things kind of have to happen in a certain way for things to progress?

Ryan: Yeah, there’s a level of trust, because when you’re doing a comic like this, everything is harder than it needs to be. You’ve got pages that need to be laid out in a certain order, some pages need to be in certain places in the book, others don’t. You’ve got the panel breakdowns that need to make sense within the page, but also sometimes there’ll be slight differences between various scenes, based on the choices you’ve made. There’s just all this added complexity that isn’t there in a normal book. And so with Chris, he was onboard from the beginning, and super down to pick up anything that I would throw at him, and I threw some crazy stuff at him. And he drew the heck out of it.

There’s one double page spread that has probably 40 characters on the page. When you write that in the script, you write an apology to the artist. There’s a couple of instances of that, where I asked for the world and he was down for it, and also you have to both be excited for the project, and we both were excited to do a Star Trek: Lower Decks chooseable path book. And so we knew there’d be some crazy things, and that’s part of the joy of the project, is pushing through and making this wild stuff happen. So it’s much harder than a normal book but hopefully worth it.

Mark: I haven’t had much of a chance to play the video game that you wrote, Lost in Random, does that have much of a branching narrative?

Ryan: Yes and no. It has one narrative, so there’s one story through the game, but it has branching dialogue. So you can choose as you play, the characters are named Even and Odd, you can choose what your version of this woman is going to sound like. Is she nice? Is she sassy? How does she interact with these people? So it gives you a light roleplaying element, without the sometimes stress that comes in a branching narrative video game, where you don’t know if you’re making the right choices, and “should I be saving before I make this choice? What if I choose wrong and I don’t get to see the other part of the story?”

I don’t know how you work, but when I play a game like that, I always want to see everything. The advantage of a book, if you stick your finger in the book when you make a choice, then you can go back and check out that other choice very easily. The advantage of a branching narrative comic is that you can see those other choices as you flip through the book, which for me is part of the fun. You see a crazy option where the Cerritos is burning up on a planet full of penguins, and you think, “how do I get there? I want to see that ending!”

Mark: There have been a few other comic book choosable path stories. There’s Al Ewing, Salva Espin and Paco Diaz’ You Are Deadpool, Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie did a short one where you’re Batman and you have to take on The Riddler. Have you had a chance to see how other writers have tackled this format that doesn’t seem particularly well-suited to the graphic medium?

Ryan: Yeah, I have, I even found an old Archie comic that was doing it. And there are different ways to do a branching narrative in comics. You can branch at the panel level, where you draw a bunch of arrows between panels, and that’s what I did in the Squirrel Girl and Galactus interactive comic. You can do it at the page level. You can do it in chunks of panels, which is what Al did for the You Are Deadpool book. There’s various ways to do it, and they each have their pluses and minuses to recommend them. For this book, I did it at the page level because that was closest to the old “Choose Your Own Adventure” books that I grew up reading and I loved. And I wanted to have that sense of the page being the fundamental unit of narrative in comics. Whether it’s branching or not, I always think of comics in terms of a page; this page is the unit of story. And to have the choices be at the page level, that gave me a bunch of very intuitive units of story that I could use to map out the narrative before I handed it off to Chris. And also it made it feel a lot more achievable. I felt if I did 200 pages of panel level choices, that would just be a total nightmare to put together.

Mark: 200 story nodes seems like a good amount, but then again, how many choosable path games have I written? The major issue, there’s a statistic that the average playthrough in a Choose Your Own Adventure book is something like 6 pages. How do you manage that problem of potentially a very short narrative?

Ryan: That’s where I try to think about the metanarrative. If you have, say, five choices for every option, then you get three choices deep, then you’ve got a combinatorial explosion of stories there. And since you’re physically limited as to how many pages you can fit in the book, you need to trim that decision tree, which means that death comes often and capriciously in stories like this. And that feels like something that I’m always in conversation with in nonlinear narratives like this.

With my Shakespeare books, my big idea there was, well, every time you die, let’s have an illustration so it doesn’t feel like you’ve lost at reading a book, it feels like you’ve unlocked an art piece in a gallery. It’s a positive thing, not a negative thing. And in Warp Your Own Way, I don’t want to spoil too much, but the fact that Mariner can die easily is part of the story of the book. If Mariner’s dying often and frequently, something seems to be wrong, right? That’s normally not what happens. And so that’s kind of what you’re exploring in the book is, well, why is this happening? How is this happening? What does it mean that suddenly Mariner is dying often and capriciously in these diverging circumstances?

I think the best version of this is when you reach an ending and it makes you excited to read the next one. And the worst version is when you reach an end and you say, “oh, that sucks, I didn’t realize if I sat in the chair instead of standing at the table, aliens would invade and everyone would die,” because that just feels unsatisfying. So one of the golden rules I have in writing stories like this, is that the effects of your choices have to be proportional to those choices. So if you do something big, you can expect a big result. If you do something small, you shouldn’t expect that it’d kill you because aliens invade out of nowhere.

It should be within the realm of possibility because if your choices can affect the whole world, if they can affect everything, then they don’t really matter. They don’t matter anymore because they’re random and wild. It’s keeping the effects of the choices scaled to the choices themselves. It means combining that with trying to make every readthrough feel satisfying. There’s no bad choices, there’s no ending where if you get it you’re like, “wow, that’s a bad ending, you need to get better at reading the book.” My goal when I’m writing is to make you feel pleased, like you’re enjoying it every time you make a choice and go through the story. So part of that’s holistic, part of that is keeping the state of the story and the game in your head as you’re writing it and understanding that every point that’s an end might be someone’s first ending. So let’s not put any bad ones in there, let’s not punish the player for exploring.

Mark: And it’s kind of the opposite issue with the Shakespeare books, because traditionally, it ends in a fail state, and it’s a big bummer designed to make you feel bad, and that’s the canon ending. Whereas you give them ways to succeed. You can give Hamlet or Ophelia a victory. But the further that you go from the canon choices in the Shakespeares, the crazier the narrative gets. How’s that different in writing for Lower Decks, where there’s no canon path, you’re writing all of it.

Ryan: Yeah, in the Shakespeare books I had what I called the spine of the story, where I knew that there would be one path through my book that would always be mapped up with the path Shakespeare made through his story. So I had that spine, that trunk of the decision tree, or enough of that.

In Warp Your Own Way, it’s not based on an existing story, so I didn’t have that spine to give you the pathway through the book. So instead there’s more of a central mystery of, “why is this happening? Who is doing this?” And investigating that and learning more about that, it gives you the structure of the story. So there is a certain level of zaniness that can happen, but it’s all grounded in Star Trek zaniness.

You look at the original series, and sometimes they would find an old colony, and sometimes they’d find a giant space amoeba, and sometimes they’d find the actual Greek gods who are aliens who feed off of human adoration. And those are three wildly different space adventures to have. And the nice thing about Lower Decks is it moves across all of those. It moves across all of Star Trek, where you can have the super serious stories and you can have the wacky space god stories, and then you could have the Borg or horrible nightmarish space zombies. And all of it fits together. And part of the joy of this book is that Lower Decks is so ideally suited to something like this. Where you could choose to go off and have these different adventures, and they all take place in the same universe and they all matter but they’re all very very different from each other, but are still internally consistent and all part of the same narrative framework.

Mark: Since the title Warp Your Own Way is clearly a reference to Fleetwood Mac’s Go Your Own Way, will there be any Antedians in the book?

Ryan: Oh my god I absolutely know why you’re asking this Antedian question and I TRULY WISH I’D THOUGHT OF THAT BEFORE WE WENT TO PRINT. Sadly, no Antedians feature in this book.

Mark: And Star Trek kind of has had a chooseable path adventure baked right in since 1982 with the Kobayashi Maru.

RQN: I’d never thought of it that way! Yes, absolutely.

Mark: And also you’ve got Boimler in “I, Excretus,” where he goes through the holodeck training program…

Ryan: Over and over…

Mark: On the hardest scenario, on a Borg cube, and he manages to 100% it.

What universe do you think is most intimidating to write in, Star Trek, Marvel, or Shakespeare?

Ryan: Oof, that’s a good question. Shakespeare was intimidating initially, because I thought when I came out with the chooseable path version of Hamlet, that Shakespeare scholars would be upset with me for desecrating The Bard. But what happened was they really enjoyed it, because I wasn’t destroying the original copies of Hamlet, I was adding onto it with new, fun ways to experience the stories, and maybe bring more audiences to the original stuff. So it was very supportive.

Star Trek, I will tell you, when we did the original Lower Decks miniseries, I thought, oh, no problem, Star Trek, I’ve seen every episode of the show, I have been thinking about it for 30 years, this is no problem, I could write a Star Trek in my sleep. And then I sat down to write it, and I was like, “oh my god, this is really hard.” And part of the reason it was so hard was every story I’d come up with, I would say, “well, I can’t do that because there’s an episode from 1968 that does something similar and I can’t do this detail, because there’s a line from an episode from 1991 that says you can’t do that.” All these walls in front of me that came from knowing too much about it. And it took me a while to get past that, because I kept hitting all these walls.

Mark: There’s a similar thing in Marvel, except that in Marvel something’s canon until it consistently gets ignored enough.

Ryan: Yeah!

Mark: Some things don’t even need to be retconned…

Ryan: They’re just forgotten. And they go away. I had the advantage with writing Marvel, with Squirrel Girl, where she was kind of off in her own corner, and so I could write that comic, and not need to know a huge amount of the larger Marvel universe. And then I had the five years that comic ran to learn more about the larger Marvel Universe. So now, writing Fantastic Four I’m not being dropped into the deep end of the pool. I got all that Squirrel Girl time to find out more, so it’s kind of the ideal way to ease into it, and not just be thrown into it.

Mark: And more generally, this doesn’t just apply to Warp Your Own Way, you’re writing the ongoing series, which starts next month.

Ryan: Oh boy, I should really get started on that, huh?

Mark: I’m sure you’ve been keeping up with the other two ongoing Trek series, Star Trek and Star Trek: Defiant. They probably can’t cross over with Lower Decks because they take place in a very specific time period where Lower Decks just doesn’t overlap. But they’ve been playing a lot, not just with the sort of regular Star Trek stuff, but also the metaphysics of Star Trek. What does it mean to be a god in this scientific universe, and things like that. But noticeably missing from that is that Lower Decks has its own crazy, crazy metaphysics, with the Cosmic Koala (“why is he smiling?”).

Ryan: “What does he know?!”

Mark: I know you’re in contact with [Lower Decks creator] Mike McMahan about what you can and can’t do in your comics. Do you have any kind of leave to write in that Black-Mountain-Cosmic-Koala space?

Ryan: I think so? He hasn’t said no. Mike’s great. The thing I’ll say about Mike is that he is 100% a comics fan, and he approaches this like, “isn’t this great, we get to make a comic. Let’s make the best damn Star Trek comic we can.” Which is so great and so refreshing. You don’t have this attitude you’re always afraid of, which is someone being like, “oh well this is a lesser medium and this stuff doesn’t count, this stuff doesn’t matter, so do whatever you want.” It’s more like, “no, this is great, let’s talk about how this fits, let’s make sure everything lines up, let’s make this feel like as much an episode as we can. Let’s make it feel important and meaningful and big and huge and let’s not be afraid of taking these big swings.” The amount of support I’ve had from him has been terrific.

Mark: It’s really funny, it seems like Mike is more closely associated with that show than any other Star Trek showrunner ever has been. Gene Roddenberry was no doubt associated with the original series, but I feel like that association came about mostly after the show was finished.

Ryan: Yeah.

Mark: Berman and Braga were mostly associated with Enterprise because people were angry about things.

Ryan: They wanted someone to blame.

Mark: It might just be a question of social media, because I feel like Ira Steven Behr and Robert Hewitt Wolfe were associated with Deep Space Nine, but they weren’t quite as forward facing at the time.

Ryan: Not to the extent of, say, JMS being associated with Babylon 5.

Mark: Exactly. And it’s kind of interesting that in this case, we have sort of an avatar of the show in real life that can be interacted with.

Ryan: It’s a real privilege to be like, “I’m going to text Mike and ask him a question.” The other great advantage of doing these comics is you’ve got a whole team there, supporting you. And there’s people on the Star Trek side who know more about Star Trek than even you do. It’s great. It’s such a fun conversation to talk about the difference between, say, a space station and a starbase and in which circumstances we should use one or the other, that fits with established alpha canon and beta canon. And there’s some people to whom that sounds like the nerdiest conversation in the world, and others like me, where that sounds so fascinating, I would love to know that difference.

Mark: I know you’ve described your run on Fantastic Four, your initial pitch was that it was going to be structured like Star Trek. They show up in a town, there’s some problem, they fix it, and maybe move on by the end. What really has struck me about it is, where Squirrel Girl mostly dealt with computer science concepts to solve problems, Fantastic Four does a lot of science popularizing, let’s say. But also, it exposes how weird science is in the Marvel Universe. So you can kind of draw a line and say, “this is the real stuff, and this other thing, if it existed in the real universe, would just break everything.” For instance, issue #26, with the skull that vomits blood and wears a little top hat…

Ryan: The top hat’s very important.

Mark: You have Reed Richards saying, “Well, if this thing exists, we solve so many science problems.” And it seems like that’s a very Lower Decks approach. It takes Star Trek concepts and points out how weird they are, for instance in the episode “Twovix…”

Ryan: I was just about to suggest that one, where they take the Tuvix conundrum, scale it up to the point where, “okay this is clearly bad, let’s just separate them, it’s fine.”

Mark: Yeah, over the years people have been calling Captain Janeway a murderer for what she did to Tuvix, but, okay, what if it’s fifty crewmembers merged into an amorphous blob?

Ryan: To me, that’s the heart of science fiction. A lot of really great science fiction stories, in my opinion, take one idea, and they add that, that’s the one added element and then explore it to its logical conclusion. And Star Trek does that a ton. Yes, there’s warp drive, transporters, all that stuff, but once you’ve got your baseline things established, a lot of the stories are, what if this one thing was different? What if this one thing happened? How does that change?

And the fun of Lower Decks is they take things like that, like you say, what if we had a Tuvix situation, but it’s scaled up. What if it kept happening? What’s the way forward? It’s really fun; it’s logical, and to me it makes the universe feel more real and more lived-in, because if we did live in this Star Trek universe, you would have people being like, wait a minute, did Pulaski cure death with that transporter move? Could we all de-age and reset ourselves? And the rest of the Star Trek universe just completely ignores it, never addresses it, but in Lower Decks, they’re like, “well, let’s look at that for a second.”

Mark: Exactly. So are you going to continue that theme of popularizing science through zany Star Trek stuff?

Ryan: Issues #3 and #4 of the ongoing series have a science concept at their heart that is real, based on reality. And it gets to be explored in a very Star Trek-y big, fun, cool idea sort of way. So, long way to say, yes. It’s not all the time, but it’s a sometimes treat for Star Trek, like you can have a story that has a Dyson sphere in it, and we all get to learn what a Dyson sphere is, and be like, “oh my god, that’s awesome.”

Mark: And the show that’s clearly head and shoulders above the rest for that is Prodigy, because it’s a lot more grounded in real science, since one of the show’s missions is getting kids interested in science.

Ryan: I wish the Prodigy time frame and the Lower Decks timeframe overlapped more, because I’m always trying to work in Prodigy references, but it’s always too soon!

Mark: Speaking of overlapping time frames, I’m trying to figure out, with the lead times for monthly comics and graphic novels being wildly different, where you have to announce the OGNs months and months in advance, and with monthly comics, you’ve got to announce it maybe a week before the solicitations come out, were you already on the Lower Decks ongoing series before the graphic novel?

Ryan: It’s just the opposite. I had already finished the writing of the graphic novel when we thought, let’s do an ongoing series. And now they’re coming out one month apart from each other.

Mark: Was it written before Shaxs’ Best Day?

Ryan: I think so! I believe so. I think I wrote it in January 2022, no that’s too long. January 2023? Time is a flat circle, who could say? Far enough in the past that I’m not exactly sure what year it was written.

Mark: Just one last thing I’d like to touch on with you before I let you go. You’ve given a lot of talks, and you’ve posted quite a bit about your thoughts on generative AI. But a few years ago, you had that early ChatGPT Star Trek account, where it was generating new episodes of Trek.

Ryan: Yes! @GPTNG.

Mark: Which was kind of like a soulless version of Mike McMahan’s @TNG_S8. I know your thoughts on language learning models, do you ever regret, say, putting it out there and kind of showing it as this kind of fun, silly thing?

Ryan: Yeah, I mean, when I was doing that, it was brand new, and I gained access to the early beta, and I was playing with it and part of the early surprise as well, was, obviously these are goofy and strange, but they’re not entirely terrible. “Isn’t this a neat piece of technology?” and I wasn’t aware then of the way there was massive copyright infringement on a global scale to train these things, and the environmental– all these issues that came with it, I wasn’t aware of then.

It was a new neat toy, in the way that autocomplete was a new neat toy, or whatever. And so it was very much early, naive, “look at this new thing! Isn’t it funny how it’s playing at writing, but obviously not that good at it yet?” If I knew then what I know now about how these things work and the issues around them, it’s not a thing that I would do. And I stopped doing it after maybe a couple of weeks.

Anyway, I’ve left it up because I’ve felt like it would be disingenuous to take it down and be like “that never happened.” And I think it’s interesting, just as a historical artifact, the fact that the changing attitudes towards it could be, early on, like “wow this is really cool, this is neat,” and then as it’s developing, it’s like, “oh there’s some stuff here that’s been glossed over, that are coming up with really serious implications.” So I guess the short answer is, yes. But it’s sort of yes with an asterisk. It’s still going on today, you see on both sides, I have a friend who really enjoys using ChatGPT for stuff, and does it almost happily, ignorant of any downside. And you see people on the opposite side who see it as a truth-telling machine. You hear about lawyers asking it for case law, and it generates fake case law.

Mark: It’s good at bullshitting.

Ryan: And you think, well, this is going to stop happening at some point. They’re going to realize at some point these aren’t truth telling machines, these have no idea of what reality really is, and it keeps happening. Because there’s always new people experiencing it for the first time. So it’s definitely still something that we’re still culturally adapting to. And it doesn’t help that these things are marketed by for-profit companies wanting you to think that this is an oracle, that this is the next generation of search engine when this is just spicy autocomplete. I find it almost offensive to be asked to read something that somebody couldn’t be bothered to write. It feels rude and I don’t care for it.

Mark: Well, I don’t want to take up any more of your time. It’s always a pleasure, Ryan.

Ryan: Yeah, it really is.

Disclaimer: As an Amazon Associate, ComicsXF may earn from qualifying purchases.