“A comic strip is like a dream… a tissue of paper reveries… It gloms an’ glimmers its way thru unreality, fancy an’ fantasy.”

– Walt Kelly, Pogo

“Okay, Lois… but who do you ask to help Superman?”

– Paul Levitz, DC Comics Presents #43

Comics are a space for writers to write down their dreams. More than that, they’re a space for readers to create theirs. And so, there are two stories in every comic book, two sets of dreams: the writer’s and the reader’s. Every reader of every issue of a comic engages with it. For every writer who used their monthly schedule as a kind of ersatz talk therapy or bully pulpit (see Alan Grant), for every writer whose ongoing became a kind of freelance psychobiography (see Chris Claremont), there was a reader that work mattered to. Comics are periodicals, with each issue intended for a certain period, intended to store and provide dreams for the writer and the reader. But some readers value them more — value them for a long time. What was just a hyper-specific time capsule for a hyper-specific era, a bizarrely revealing document of the dreams and nightmares of a certain person in a certain era, can become a storehouse of the dreams and nightmares of writers and fans now long past.

Researching those dreams means researching fandom, and researching fandom almost feels like archaeology or anthropology. There’s inevitably a distance that has developed where the pages don’t read the way they ought to on a laptop. Time has passed, and now they feel more faded than ever. They’re past their prime, certainly: The fandom historian (and former arch-fan himself) Sam Moskowitz once said the golden age of science fiction was about 12. The golden age for fandom is probably later than that, but a similar principle applies — the golden age of fandom is all too brief. When you look back at the zines printed by so many devoted fans in bygone amateur press associations (zine distributors, basically), when you see the slyly horny fanart, the witty, impenetrable articles and poems, you see something well past its golden age.

The one blessing a fandom researcher has is that, frankly, fandom hasn’t changed very much: People first started cosplaying in 1939. The only real change to fandom in 90 years is that it operates more quickly and on a larger scale than it once did, because the media it uses is better. Once, everything occurred by mail; now, we haunt message boards and Discord servers, for much the same reasons (though I do think that the poetry old-time fans wrote has been undeservedly forgotten. I mean, it ought to come back. There is nothing like a really terrible fan poem).

Yet for all this, for all that the fans who wrote to Stan Lee or Mort Weisinger are immediately recognizable as comics fans, the comics we read today seem to have had their pasts as fan objects clipped away. Reprints and digitized collections offer stories, but not in full. How could they? Time has passed — even if you were to carefully include every letters column and house ad (and I do think they should do that, frankly) you couldn’t include the full context of what a comic once was. That’s the nature of a periodical: Its history starts to vanish the moment the next issue is published.

Of course, there are ways of reconstructing contexts. I like it a lot when reprints include critical essays and useful historical notes. (Ben Saunders’ work for the Penguin Classics Marvel Collection is, to me, a model for how we ought to approach comics.) A comic may have aged very well, or very poorly, but it has obviously aged. It would be intellectually dishonest, not to mention just plain wrong, to say the world is the same as it was when Amazing Fantasy #15 hit the stands. There’s history to acknowledge, and it gets acknowledged, or some of it does. We often see acknowledgements of world history, but what about fan history? Where is that?

If it’s not entirely gone, then it’s a footnote. That’s what happened to Legion of Super-Heroes: Once the ultimate fan comic, it’s now the ultimate footnote. But we as readers, critics and fans wouldn’t be here without the Legion. I wouldn’t be writing for ComicsXF without them. I think there wouldn’t really be X-Men fandom, or modern comics fandom, without the Legion. Yet the Legion, the book about teenagers from the future, is dead. Theirs is a future that’s been — if I can channel Kieron Gillen briefly — totally canceled.

Why? Whatever happened to the Legion of Super-Heroes?

Let’s start at the beginning. Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: In the 30th century, the richest man in the universe is getting out of a public shuttle. The kindly old duffer could take his own, but he doesn’t like to. He wants to keep the common touch, though he makes stars for a living. Suddenly, rayguns are drawn on the old man. All seems lost — and then, three super-teens in brightly colored lycra tunics jump out. Super-lightning, super-magnetism and super-thought-casting coruscate wildly. The richest man in the universe is saved.

Later, immensely grateful, he tells the three super-teens about his dream. A long time ago, there was a boy from Smallville who could do anything. Why couldn’t there be boys and girls like that again?

He asks them if they’d like to be super-heroes. Stunned, they say yes.

Then he asks if they’d like to travel back a thousand years and ask Superboy to join them.

They say yes to that, too.

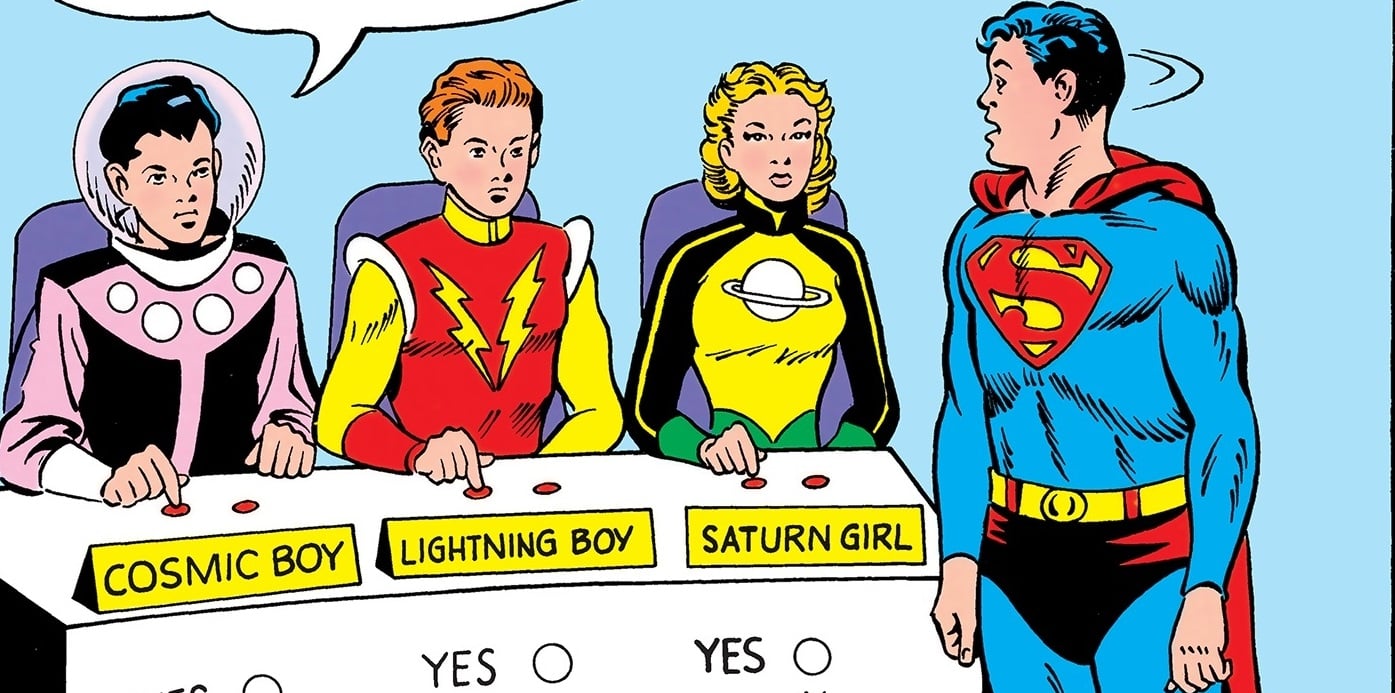

The story of the Legion of Super-Heroes begins that way, with Lightning Lad (Garth Ranzz of Winath), Saturn Girl (Imra Ardeen of Titan) and Cosmic Boy (Rokk Krinn of Braal) saving the life of the irascible old dreamer R.J. Brande. But like most things with the Legion, it’s not that simple. For one thing, the Legion doesn’t really begin there. The story I just told you is a retcon, established well, well after the Legion first appeared on the rightfully famous cover of Adventure Comics #247:

For another thing, the origin of the first Legion doesn’t really matter anymore. Their story and R.J. Brande’s dream ended in 1994’s Legion of Super-Heroes #61 — and though fans might not have known it yet, a larger, shared dream ended, too. Today, the Legion is probably best known as where Nightcrawler isn’t. If people know it at all, then it’s as the series Dave Cockrum worked on as a young ex-sailor with far too much passion, reinventing it before DC’s staid conservatism nixed his proposed new Legionnaire — “Murray Boltinoff’s response was that [Nightcrawler] was too weird looking,” remembered Cockrum, and he decamped to Marvel. Cockrum left the Legion’s enormous cast, its hokey Silver Age adventures, its battles against space sorcerers on behalf of the United Planets (think the Federation in Star Trek) and the Science Police (yes, really) behind, exchanging them for the X-Men. The implied corollary to that statement is that we should leave them behind, too: The rest is, after all, history.

But it is worth considering where that history began. The Legion predated Dave Cockrum’s involvement by nearly 15 years. Through all that time, the team had been boldly defending the United Planets throughout the Superman family of titles. It predated even that, too (it’s true, the Legion is complicated). The world of the Legion is one where utopia is a household world. Legion is a comic set in the raygun paradise predicted by the Golden Age of Science Fiction, and its Lads and Lasses and Boys and Girls protect that ghostly yet perfect dream of the future.

It’s only fitting, then, that the Legion was created by the veteran science fiction writer Otto Binder, who, aside from his career as half of pulp legend Eando Binder, had woven extensive tales of the Marvel Family (Captain Marvel, Mary Marvel, Captain Marvel Jr., the Lieutenants Marvel, Hoppy the Marvel Bunny) for Fawcett. When DC conquered its rival publisher, it brought Binder onboard, to do for Superman what he had done for Captain Marvel: make him a family. His most enduring creation is, of course, Supergirl, but the Legion can’t be ignored. Binder created them not as Superboy’s family, but as his friends.

In Smallville, Superboy had friends like Pete Ross and Lana Lang, but he had no one like him. He was alone. But in the world of the super-heroes, he had friends who understood what it was like to have the emotions of a child and the powers of a god. It was there that he could grow up, crush on girls (though in truth Duo Damsel was more attracted to him than he to her), and confide his problems to a surrogate big brother, tortured Mon-El. There, he could know what it was to fail, to suffer, to grow. He couldn’t do that back in Smallville, not when he was fated to become the world’s most perfect hero. (It was this belief, that nothing ever changed or happened, really, in Superboy stories, that ultimately led John Byrne to eliminate Kal-El’s youthful career, and, in so doing, eventually eliminate the Legion.)

The Legion was set a thousand years from the time of publishing (2958 as opposed to 1958, say). The Legion eventually even ran in “real time.” So the Legion did not need to obey the procrustean laws of continuity keeping comics set in the eternal “present.” In the Legion, people could die and grow — they didn’t really matter. Only the immaculate Superboy did, right? But soon, the 30th century became far more than Superboy’s playground. Even today, the joy Binder’s successors, old science fiction pros like Superman co-creator Jerry Siegel and the “world-wrecking” pulpster Edmond Hamilton, must have had in further building this Gernsbackian world is palpable.

Every story introduced Superboy to new characters, like the brilliant Brainiac 5, jovial Bouncing Boy and the jail-wall-devouring Matter-Eater Lad. Soon, Superboy felt more like the Snapper Carr or Rick Jones of the title than its star. He was a guest in the ever-vaster world of the future, as opposed to the fans, who felt as though they knew this future well. Binder, Siegel and Hamilton had been 12 once — they had all had their own golden ages of science fiction. Pulp had changed their lives as children, and now there were new children. They felt an obligation to that new generation, an obligation to create for them a new future world to play in, a world that wouldn’t blow itself to bits with atom bombs.

The thing sites like Superdickery miss about the Silver Age is that it exists not in a world of realism, but expressionism. It’s written for children, and it very candidly acknowledges the fears and worries of childhood. As Maurice Sendak once said, “Childhood is cannibals and psychotics throwing up in your mouth!” — or at least it feels that way. The world seems vastly stranger, more violent and darker than adults will tell you.

But the Legion, in a way, did tell its readers what the world was really like: not in an realistic way, no, but in an expressionistic one. Hamilton’s Legion stories lived up to his world-wrecking reputation. Despite his young audience, his stories are often bizarrely, disturbingly dark. “Mxyzptlk V” once killed the entire team; even when it was reversed, a traumatized Superboy still remembered everything. When Lightning Lad died in battle, saving the Earth from an alien conqueror, the Legion, over the course of quite a few issues, strove to bring him back. They finally found a way: For Lightning Lad to live, a Legionnaire would have to die. Saturn Girl, a little in love with Lightning Lad, was intent on making the sacrifice herself — but it would be Chameleon Boy’s bizarre little pet Proty, a shape-shifting, amorphous blob, who ultimately made “The Super-Sacrifice of the Legionnaires.”

Don’t read it as camp — Hamilton meant it to be emotionally real, just childlike. Read it as a story about obligation, about enduring after tragedy, about living with loss, about survivor’s guilt and true nobility, that just happens to be a children’s story about a weird little white blob. Read it like this, and you’ll understand what made the Legion so special for so many people. Read it, in other words, as seriously as we today read the X-Men.

The comparison seemed forced at first: The similarities between the two series seem superficial. With the coming of the Marvel Age of teen angst, superhero soap operas were a dime a dozen — so what if the Legion came first? After all, the two teams are so different: A friend observed to me recently that they’re almost ideological opposites. The X-Men fight for Xavier’s dream and to keep a dystopian sword of Damocles from falling. They know the world could all too easily end up under the heel of the Sentinels or the “evil mutants.” The Legion, meanwhile, fight because of another dream, one implied by the existence of Superman, who is, in Alan Moore’s perfect phrase, the “perfect man who came from the sky and did only good.” In the 30th century, Gotham is just a suburb of the seaboard-spanning hypercity Metropolis. The night terrors the Batman fought have finally been vanquished.

Yet the series do have something fundamental in common: the Kate Bishop-esque idea that everyone can be a superhero. While the people of Earth-616 view mutations as a racialized threat, the 30th century hosts competitions (the famous Legion tryouts) to see who is the most different of all. In these trials, some applicants always come up short, but not before leaving a distinct impression of their individual personhood, the distinct impression that they have a life off-panel somehow.

Every single superhuman the reader encounters seems to have a life, a story, a point of view and, of course, an extremely silly futuristic name, of their own (my favorites include Ulu Vakk, Quelu Ord/Ord Quelu, Reep Daggle, Stig Ah and the outliers Douglas and Andrew Nolan). There is so much difference, so much marvelous variety, that failed applicants formed their own team, the wonderful Legion of Substitute Heroes.

Where did these bizarre and brilliant super-teens, all of whom had names and faces, hopes and dreams, come from? Some of them came from readers. The story of the Legion is incomplete without the names of Otto Binder, Edmond Hamilton and Jerry Siegel – but it’s also incomplete without names like Tom Kegley of St. Paul, Minnesota, who, in Adventure Comics’ Bits of Legionnaire Business column, pitched “BLOCKADE BOY – he can change himself into an invulnerable steel wall of any size or shape.” Blockade Boy later died a hero’s death in the Super-Stalag of Space. The Legion is so special because its creators include names like Leslie Leibow of Fair Lawn, New Jersey, whose “COLOR KID” could “change the color of any object.” He became a longtime member of the Subs, once saving Superboy’s and Supergirl’s lives by changing deadly green Kryptonite harmless blue. Legion history would be made by Jim Tilley of Rockaway, New York: His creation “SPIDER LASS,” with “the power of converting her hair into a super web, and casting it around opponents” became a galactic super-criminal, then reformed, then joined the team. (Were Tom, Leslie and Jim compensated for their creations? I doubt it.)

From its very earliest days, Legion was a comic by and for its fans, as the writing tenure of “our latest discovery, 14-year-old James Shooter” showed. Shooter, later the infamous editor-in-chief of ‘80s Marvel, began life as a fan, if a more mercenary one than most. With astounding chutzpah, at the age of 14, he wrote to DC, asking if they wouldn’t like an actual kid to write the Legion and help them beat Marvel’s growing sales. They said yes. His run, which introduced such franchise fixtures as Princess Projectra, Shadow Lass, the satanic sorcerer Mordru and the evil Fatal Five, became a classic. Mark Waid is only one of many admirers: He once called Shooter’s Legion the “blueprint” for his entire career.

Almost uniquely for the Silver Age, the Legion had a tight sense of continuity. It must have come from writers and readers wanting to know what happened to the characters they’d come to regard, not at all wrongly, as “theirs.” That sense of having a stake in the world of the comic served as a kiln for a growing fandom, which soon grew into something rather like the Legion itself. It was a tight-knit group, perhaps a little exclusive, a little tenuously linked to the rest of DC, but it was a group utterly devoted to R.J. Brande’s dream. When the Legion left its regular place in Adventure Comics due to editorial shakeups, fandom saved it from limbo, and had it return as a backup title in Action. Later, fan response to Dave Cockrum’s gorgeous Legion art in the pages of Superboy proved so overwhelming that that book’s title soon changed to Superboy starring the Legion of Super-Heroes.

When Shooter left comics (the new page rates were too low to support his father, a miner), fandom brought him back for a second, extremely sweaty, run — we have Legion fans to blame for Jim Shooter, I suppose. But the series had soon moved beyond him to become something self-sustaining. By now, fans, artists and writers eagerly joined and corresponded in Legion zines like Legion Outpost or Interlac (named for the auxiliary language, uncannily like 1970s English, spoken by everyone in the Legion’s galaxy). Dave Cockrum drew covers for The Outpost: he wrote letters explaining why he changed characters’ costumes, and groused about which characters he’d like to kill given the chance.

Even before this, the comics themselves had acknowledged the debt they owed fandom, in features where, like paper dolls, the Legionnaires showed off their new, fan-designed fashions. (Mercifully, these you see below did not last because they are terrible and Dave Cockrum was the best superhero costume designer since Jack Kirby — but Saturn Girl wore a fan-designed costume, a pink number designed by one K. Haven Metzger, for a decade).

These Legionnaires were a far cry from the chaste youths of the ‘50s and ‘60s: It was the 2970s, baby, and the readers knew it. Cosmic Boy wore a corset and went bare-chested; Dream Girl and Star Boy were clearly having sex every time they went off-panel; Karate Kid and Princess Projectra could not keep their hands off each other. The book was growing and changing with its readers in the new decade, and every year, something new would happen. Every year, fans could vote on who should lead the Legion next. Parasociality began to exist between the readers, the writers, the artists and, of course, the Legionnaires themselves. Slashfic reigned, as it always does — I’m reliably informed that Mon-El and Ultra Boy (though he has all Superman’s powers, he can use only one at a time) were a favorite pairing. Cockrum’s successor as artist on the title, Mike Grell, drew Legion erotica for fan delectation (you can find some here). Superfan and cosplayer Mercy van Vlack had a planet named after her. That’s what Legion fandom was like.

Interlac’s Harry Broertjes writes that “lives, in greater or lesser measure, were built on the seed of Interlac membership” (that is, through Legion fandom). He’s right. Fans Mary Gilmore and Tom Bierbaum met through Interlac and got married (we’ll hear more of them later). Legionnaires married, too. First it was Bouncing Boy and Duo Damsel, then Lightning Lad and Saturn Girl. By the 1980s, they had twins. As the years passed, the Legion changed: New members joined in fearsome yet gentle Blok, star-crossed Wildfire and his would-be love Dawnstar (think Rogue and Gambit only much, much more annoying). Mainstays like Invisible Kid and Chemical King died, and stayed dead.

Times were changing, from Nixon to Ford to Carter to Reagan, and science fiction changed, too. William Gibson penned “The Gernsback Continuum” in 1981, a story in which the Golden Age dream was presented (not wrongly) as vanished, terrifying and forever lost. Now, Frank Miller was writing a darker, angrier Daredevil. Chris Claremont — joined by Cockrum, whose Legion work Claremont adored — was writing X-Men. But the Legion didn’t change, and neither did the dream. The fans only grew more passionate, more devoted, more eager with every passing year — and their hopes were, it seemed, only vindicated when the title entered what many see as its peak.

Want to know what happens next? Click here for Part 2, Legionnaires!

Margot Waldman

Margot Waldman is a Mega City Two-based scholar, researcher and writer. Her great loves are old comics, Shakespearean theater and radical social justice – in no particular order. One day, she hopes to visit the 30th century.