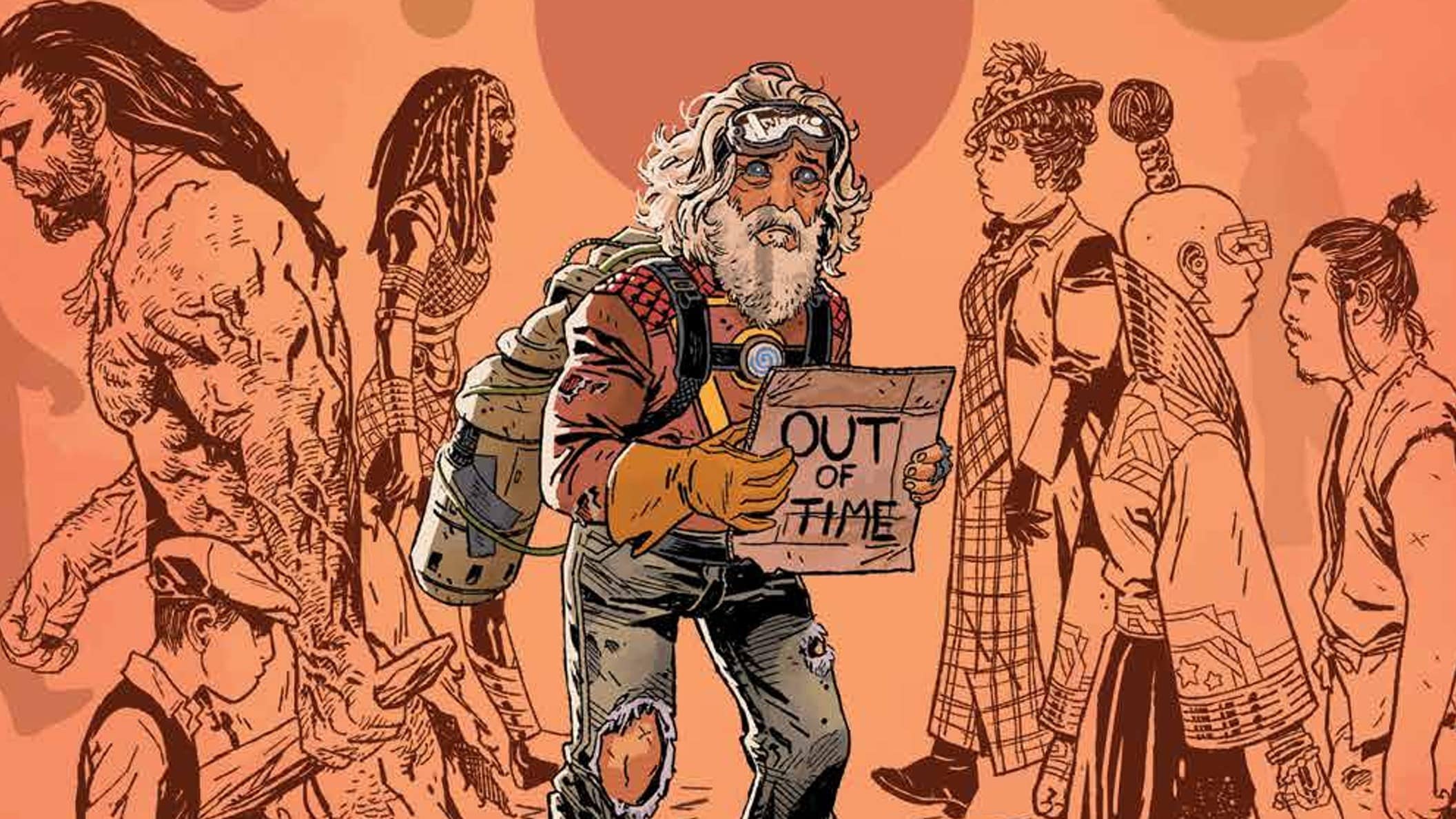

What stalks the blood-soaked kill floor? A dizzying, heartbreaking, hallucinogenic trip through the endless slaughterhouse! Witness a man’s life cut up, ground down and packaged for easy consumption in Assorted Crisis Events #2, written by Deniz Camp, drawn by Eric Zawadzki, colored by Jordie Bellaire, lettered by Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou and designed by Tom Muller for Image Comics.

After putting down the first issue of Assorted Crisis Events, my first thought was: How do you top that? It covered the baffling horrors of the contemporary human experience so well that it was hard to imagine where Camp and Zawadzki would take it next. Where issue #1 captured how modern life felt, issue #2 zooms in on the gruesome reality of how it is. Where Ashley, the focus of #1, was free to roam the streets through movie sets and hyper-real fictional apocalypses, the life depicted in issue #2 is one of constraint and repetitive monotony. The focus in this issue shifts focus from a bohemian, white middle-class experience to the modern American immigrant experience.

Through the life of Jesús, a first-generation immigrant in America, it dissects the twin promises of hope that power the machinery of industry, religion and the American dream, and how they create cycles of bondage from generation to generation. It also explores how the impact of generational trauma on Jesús’ ability to participate in the “food chain of being” has cascading effects on his mental health and sense of identity as well as his economic freedom. Within this cycle, Jesús becomes his father and fears that his suffering will pass on to his daughter. It’s brutal, confronting and tragic, but absolutely vital.

Papers to exist

The most significant shift in focus from the first issue to the second is that the universal becomes more personal. Jesús’ life, and his family history, are integral to the narrative in a way that Ashley’s wasn’t in the first issue. Barely escaping their dangerous passage, Jesús and his parents arrive in America full of hope and ambition. Jesús’ father, Alfonso, finds work in a meat factory where he’s responsible for the slaughter of hundreds of cows a day, a job that (contrary to his co-workers’ and mandated therapist’s perceptions) wears him down over time and drives him to alcoholism. He dies in a tragic accident at work and is shortly followed by Jesús’ mother, with their hope for a better life having not come to pass. Jesús takes up his father’s work but finds himself unable to deal with the relentless slaughter of animals. He follows the same tragic path as his father, succumbing to alcoholism and eventually being laid off.

The cyclical nature of Jesús’ story is mirrored in the structure of the issue. The narrative doesn’t just jump around in time; the past bleeds through the page onto the present. Zawadzki’s use of stencil-style art, which is an underlayer to the action in the present, creates an effect whereby the generational trauma of Jesús’ life, which is symbolic of the immigrant experience, impacts his freedom in the present. Its degrading effect on his mental health and ability to find a job that’s suitable for his skills and temperament is tragic because it is so relatable to the real-life experience of so many. This is the story of a man overwhelmed by life, but whose economic conditions force him to live every bit of its gruesome reality.

Given how frequently these issues are generalized, it’s fair to ask the question: Why is Jesús’ story symbolic of the immigrant experience?

Just as the focus of the narrative is more personal in issue #2, its engagement with context also becomes more specific. Camp weaves multiple contemporary American immigration policies into Jesús’ story, and emphasizes their dehumanizing effect. Allusions are made to the separation of mothers from their children at borders and citizenship papers dictating someone’s right “to exist.” What works so well is that, by having past events bleed into the present narrative, Camp and Zawadzki always connect it back to the individual.

The most powerful example, to me, is the allusion to the treatment of “essential workers” during the COVID-19 pandemic. Exposing low-paid frontline workers to heightened infection risk to keep powering the economy while white-collar workers remained in the safety of their homes is as symbolic of a real-life class divide as you can find — patronizingly elevating them to a new yet inevitably temporary social class is downright dystopian — yet it really happened. As Jesús faints at the sight of the horrors he’s made to endure, Camp uses narrative caption boxes over Zawadzki’s beautiful, downward-cascading panels.

“There’s a moment … a precise moment where the animal goes from living thing to food. Goes from meaningless to sacred. From superfluous to essential.”

Concepts like death, ritual sacrifice and disposability are evoked in this passage, characterizing the dehumanizing effect of the immigrant experience of the past decade. The circular motion created by the panel layout further emphasizes the cyclical nature of this experience, suggesting the essential will again become superfluous. This echoes the political reality of post-COVID Western civilization.

Crucially, this passage is spoken by Jesús’ white co-worker, who is talking about the slaughter of cows over the image of Jesús falling, drawing parallels between the two. This is the issue’s most provocative piece of symbolism, and it pervades the entire issue.

The Food Chain of Being

There are two key metaphors Camp deploys in the issue to connect the treatment of immigrants to cattle. The first refers to the “food chain of being,” which symbolizes the broader immigrant socioeconomic reality. Camp deploys dramatic irony via Jesús’ boss to introduce the concept, which is prefaced by his patriotic description of the factory workers’ “essential” role and being “part of something.” The character’s intent is to describe their role in powering the nation, providing their fellow citizens with sustenance to contribute to the nation’s wider prosperity. He’s referring literally to the food chain involving man and beast. Dripping with irony, Zawadzki overlays the scene with images of Jesús’ dad eating a hamburger, representing the hope of attempting assimilation in horrific fashion.

Even more tragic and ironic are Jesús’ flashbacks to his father’s death, which is depicted as his body literally being put through the meat grinder. When you couple this imagery with the repeated use of the word “essential,” the true meaning of the phrase “food chain of being” comes to light. Those exposed to the trauma that is required to feed the nation are consumed by it also. Jesús’ mental health difficulties, manifested in his alcoholism and traumatic flashbacks (represented here by ferocious dinosaurs), have real-life consequences for him. The fact that his co-workers don’t treat him as an individual person, that they assume that “you people” are hardened to the grim realities of their role in this global system because they have no choice, is a further example of how immigrants are dehumanized. When it comes to Jesús, his job, his daughter, his very sense of identity are all chum for the voracious food chain that is life.

Washed in the blood

The second key piece of imagery is more complex, more focused on the individual. In the scene where Jesús recounts the slaughter of his 151st cow of the day, he begins to empathize and relate to it. He imagines the cow’s life from birth, its innocence slowly eroded by its experiences of being kept in cages with thousands of others, of being force fed and separated from its mother. Both phenomena are examples of the dehumanizing conditions immigrants experience as a result of hardline policies. Camp and Zawadzki again overlay the scene with imagery connecting Jesús with the cow, with scenes of dinosaurs chasing him symbolizing the re-emergence of past trauma. The scene is also punctuated by a sermon. The narrative caption box from the sermon asks “Are you washed in the blood of the lamb?”

This takes on a cruel irony given the scene unfolding before us because in context it is supposed to symbolize the hope of God’s love and protection. This hopefulness is contrasted on page with Jesús mourning his mother, who represents the death of their American dream. The ironic connection with religion is further punctuated by a memory of his boss saying, “Call this the promised land.”

Camp then begins to weave the cyclical nature of this hopelessness into the narrative: “I see the way its whole sad life echoes … the worst parts repeating again and again.” This represents the nature of trauma as it passes through generations. Without the freedom to break the cycle, the suffering and the death go on and on. Again, the hope offered by religion and by his parents, at least in this story, was false.

The final two pages are a brutal reminder of this. On the penultimate page, which Zawadzki structures as four panels floating like boats to America over a lake of blood, Jesús faces his death. At first he is terrified, but he eventually accepts it. The final page is even more devastating, as Camp brings the cycling parallel narratives to a close. The narrative caption connects the primal instinct of cows seeking the safety of their mothers in the moments before their death with the immigrant experience. The final scene of Jesús embracing his family again conveys this very human desire for comfort, to return to a time when there was still hope and optimism for the future.

This issue is much bleaker than the first, with little humor to offset the tragic depiction of contemporary life. The sheer number of parallel voices and repeated narratives, combined with the 30+ page count, makes it dense and heavy going at times. Crucially, though, you can’t say this comic didn’t achieve its objective or communicate its message clearly by the end of the issue. As well as being a razor-sharp critique of America’s immigration policies, it establishes a profound pathos for the lead character. This series is confronting and uncomfortable at times, but Assorted Crisis Events is always compelling, moving and essential.

Buy Assorted Crisis Events #2 here. (Disclaimer: As an Amazon Associate, ComicsXF may earn from qualifying purchases.)

Jake Murray spends far too much time wondering if the New Mutants are OK. When he's not doing that, he can be found talking and writing about comics with anyone who will listen. Follow him @stealthisplanet.bsky.social.