As Doctor Doom prepares a fatal strike against those who stand against him, a sudden betrayal has Cap on the ropes and questioning everything he thought he knew. Captain America #4 is written by Chip Zdarsky, drawn by Valerio Schiti, colored by Frank Martin and lettered by Joe Caramagna.

Part of me – part of all of us, maybe – needs a kind of primal animal justice. We need to see a bully beat up so bad that he looks like the little twerp he really is. I think this need is in large part what drives me to read about Captain America, frankly, and though it is not a very intellectual desire, I truly think it is a very raw part of the character’s appeal. Captain America Comics #1’s promise to its reader is pretty well known, I think.

(This is, as the kids say, based.)

True, it takes a few more issues for Cap and Bucky to physically make their way to Hitler’s Germania and absolutely just fuck him up, but the damage was done the moment the first little kid saw this cover. That kid saw – to his joy or to his terror – that the imagination could produce a tool able to fight back against fascism, a tool able to satisfy the gut need to destroy a bully. This comic book was, quite simply, an ideological part of the arsenal of democracy – if a naive one.

I suspect a reason why the Golden Age crested and peaked is that by 1945, this kind of imagery was a little too simplistic in the midst of mass death and mass murder. What could a single right cross really do or really mean? It took a kind of rebuilt atom age naivety for Americans to pretend this kind of shadow-and-lightning story could work again – but we have always been eager to pretend, to see ourselves in such comically naïve terms. The greatest country in the world, we call ourselves, with the greatest system of government in the world. An American doesn’t have to read Marvel Comics to be a true believer.

You don’t have to read my writing to know what’s wrong with that unalloyed my-country-right-or-wrong mentality. You don’t need to read Captain America to know it either. But I think if you wanted to read something about it – about what it means and what it does, what it looks like, and why it’s worth still telling stories about Captain America – you could do a hell of a lot worse than Captain America #4 by Zdarsky, Schiti and Martin.

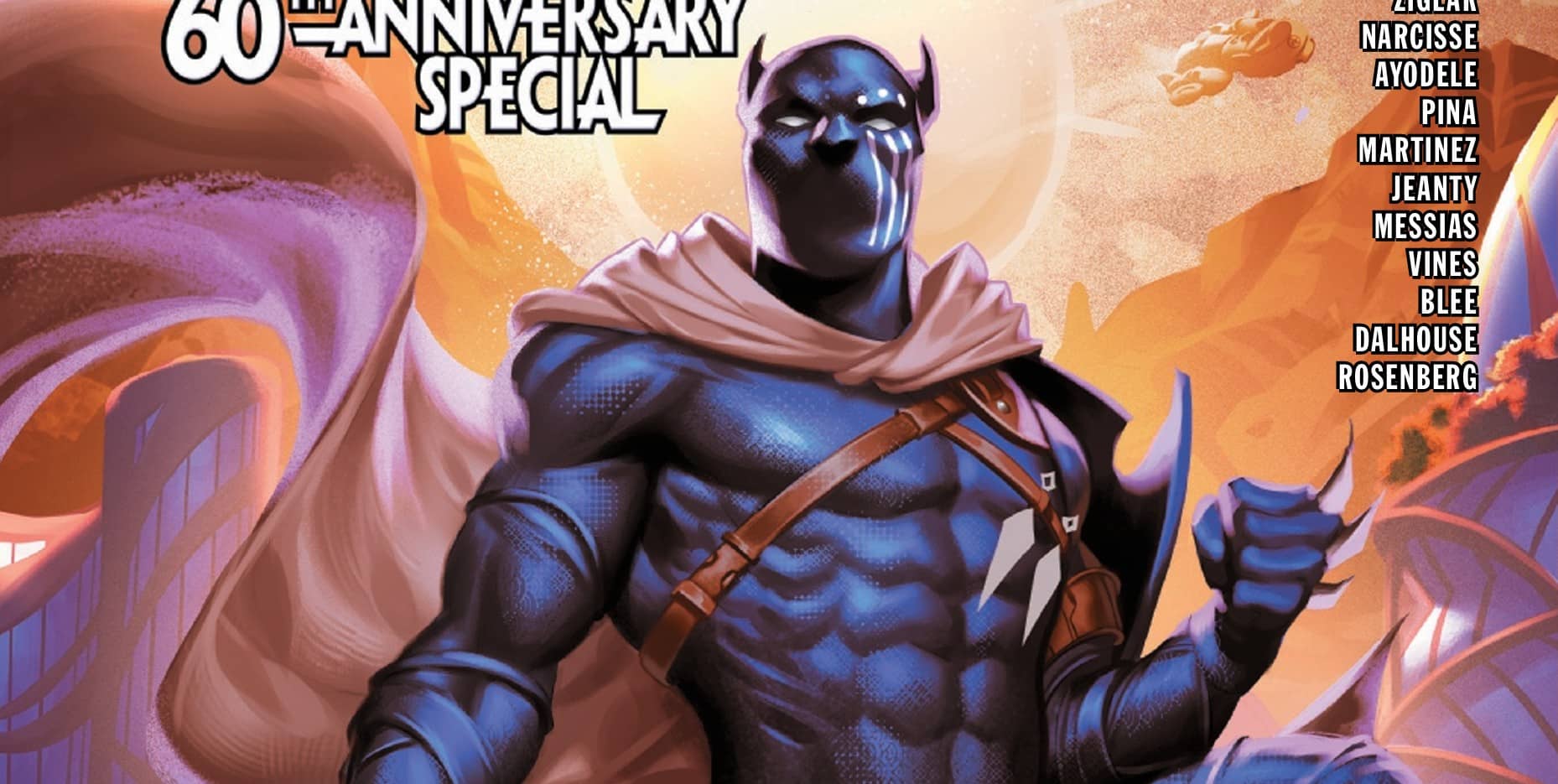

There is not much that is intellectual about this image, I’ll admit. But it is very nice to see and it makes me feel rather more optimistic because it is an image very much in the spirit of the original promise Captain America made.

(This is also, as the kids say, based.)

This is the idea that the man in the street has of locking up the doors of the Congress or the Parliament so that all the leaders can agree to something writ not large but superhero-size. This is true belief – naïve belief. But in a superhero comic, that earnest charming faith prevails. A little guy from Brooklyn can go up against a tin-clad Ruritanian despot, and because he believes in the right things and the moral way forward, he can win.

At their best, I think Marvel Comics are broadly about that victorious scrappiness, about a little guy punching a dictator in the face so hard he looks like a punk. Doctor Doom is built for this kind of thing as a character. He is really engaging to see lose. It is just satisfying as hell to see Doom slink off as a miserable little figure in a cape in the 1960s, right?

Well, it’s still satisfying.

It’s still satisfying to see that naïvety – but we also know what that naïve belief in essential rightness looks like now. We know what it’s done to us as a country – made us believe so strongly in American exceptionalism that we have become exceptionally cruel and exceptionally vile. A friend pointed out to me that in a past era, a past comic, this issue’s little twist-revelation – that the U.S. government wanted the hostages David Colton and Steve Rogers are there to save dead – would be a twist, would be the issue ender, the full-page splash, a gasp line. America, doing something immoral to save face? How could it be?

Nowadays, no one is naïve enough to not see this sort of thing coming – nobody except for David Colton.

Toward the beginning of this issue, Colton says he won’t throw his shield – it’s impractical, it doesn’t work, like a boxing-glove arrow or a mercy bullet. That, he says gruffly, is the other guy’s cliche – his trademark is impossibly knowing and believing that this talismanic thing of his, this symbol, will return to him, always coming back to rest by his side. Sing it with me: “When Captain America throws his mighty shield…” It’s an emblematic piece of American apple pie naïvety, that the shield always comes back.

Colton doesn’t subscribe to this, he claims. He pleads the laws of gravity, the laws of reality: “I throw this and they suddenly got a shield.”

Toward the end of the issue, Colton throws his shield. It’s impractical, it doesn’t work – at least not as a weapon in a superhero comic. It works as a sharp disk of metal cutting a woman’s chest open would. David doesn’t throw out of blind, cheery faith – he throws as a murder weapon. He throws and knows that what he’s thrown won’t come back. The monster knows he is a monster now, not a hero.

The only way to proceed is to double down, regroup, rebuild his morality, rebuild his exceptionalism.

To do that, there can be no survivors.

Buy Captain America #4 here. (Disclaimer: As an Amazon Associate, ComicsXF may earn from qualifying purchases.)

Margot Waldman

Margot Waldman is a Mega City Two-based scholar, researcher and writer. Her great loves are old comics, Shakespearean theater and radical social justice – in no particular order. One day, she hopes to visit the 30th century.