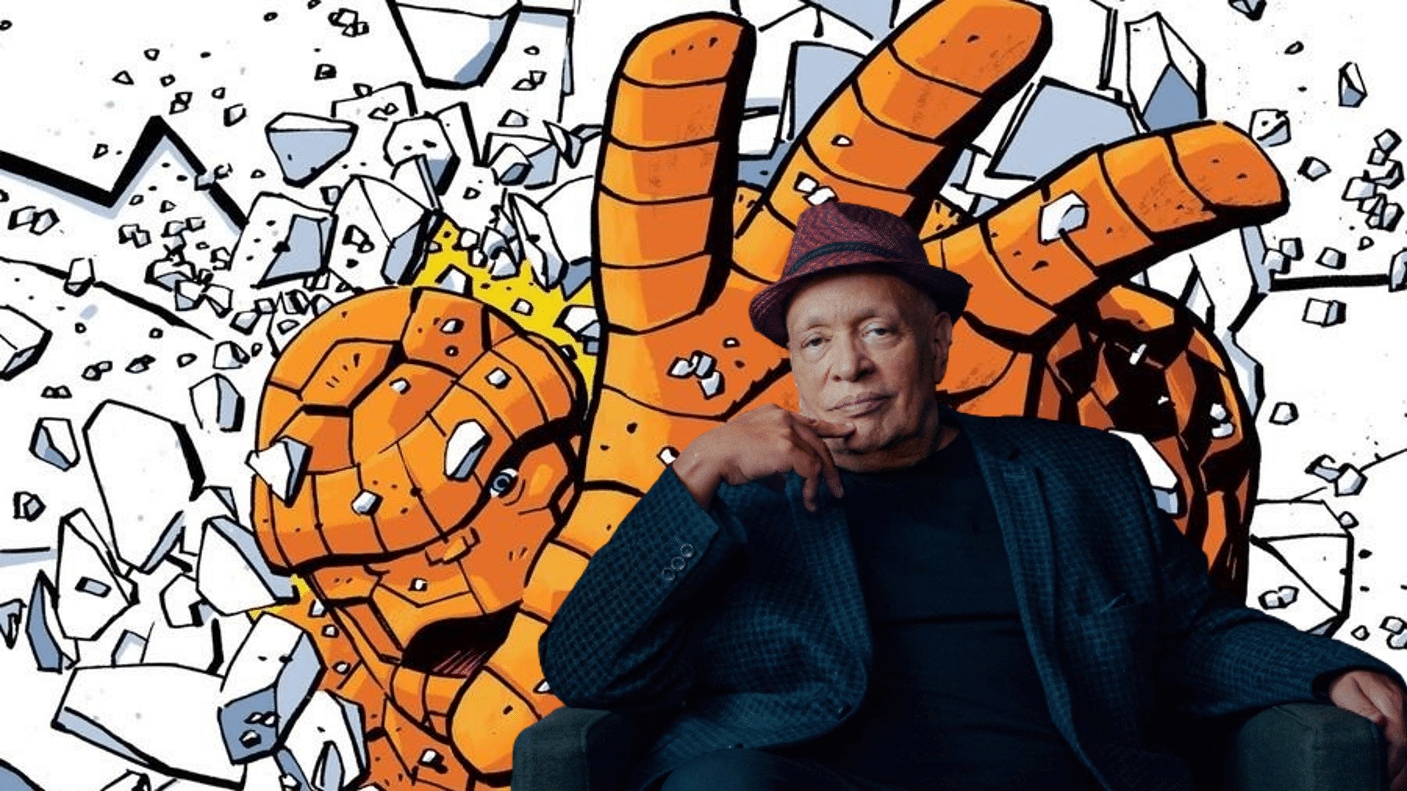

Walter Mosley shouldn’t need any introduction. The acclaimed author of more than 50 books, including his famed series of Easy Rawlins mysteries, Mosley’s work has been adapted into film and television, and earned him a series of honors ranging from the O. Henry Award to the National Book Foundation Medal. What comic readers might not know is that Mosley has also been a fan of Marvel comics for four decades — a passion that resulted in his 2005 project Maximum Fantastic Four, and got him name-checked on the Luke Cage TV series.

Next month, Mosley teams with artist Tom Reilly for a six-issue Thing limited series. On the eve of its release, Mosley was kind enough to sit down with us to chat about comic history lessons, the Marvel Universe, and what DC heroes have in common with Playboy centerfolds.

Zach Rabiroff: You’ve been a comic book reader since way back. How did you first get into comics?

Walter Mosley: I was talking to somebody the other day, and we were remembering going to the barbershop. And in the barbershop, there were always stacks of magazines, and one of the stacks was comic books. The first comic book I remember seeing was…what’s the comic book that the Legion of Super Heroes first appeared in?

Rabiroff: Oh, Adventure Comics.

Mosley: Yeah, Adventure Comics. And it was Cosmic Boy, Saturn Girl, and Lightning Lad sitting as a jury, and Superboy was on trial. I was 10, maybe 9. And they also had racks of comics in the grocery store, and I remember seeing Batman and Robin going up against the Bizarre Polka-Dot Man. So then when I was 11, going on 12, I walked a different way from my parents’ house to a store, and they had Fantastic Four #15 — that’s the one with the Mad Thinker and his Awesome Android. And I thought, “this is good. I understand these characters. I identify with them more.” That was my transition to Marvel, almost immediately.

Rabiroff: What was it that you saw in those Marvel stories that appealed to you more than DC?

Mosley: Their characters had flaws. [Laughs] I remember also sneaking in to look at my father’s Playboy comics. And I remember the women, and at first it was really exciting and interesting, but after a while it’s like, “there’s too much perfection here.” It’s the same thing [with DC]: I just didn’t identify with it. At Marvel, there’s the Thing who speaks in a kind of a dialect and is tough, and you have the Human Torch who has a hot temper. Mr. Fantastic is about science, and the Invisible Girl who didn’t have much personality then but transitioned into a much stronger character in the next two years — I felt like they were all much more realistic.

And then the villains, especially the Sub-Mariner: he’s a guy who’s a villain to us in the surface world, but he’s a hero and a king to his people below the surface. So the whole concept of a hero/villain…Marvel was ahead of DC to write all that stuff down.

Rabiroff: So looking at Ben Grimm, what do you think makes him tick as a character? What’s at the heart of the Thing?

Mosley: I have, in one of the comic books, a scene where he’s filling out a virtual form: name, height, weight, race. And when it says “race,” he looks at his hand and says, “uh, non-white.” And I that’s what I think about the Thing. In my understanding, he was the Black character, and I most identified him. Of all the characters, I loved him the most. He’d go through a door and break the door frame — he was always doing something wrong, but for the right reasons. He’d get mad, he’d get upset, but you always felt he was the most gentle and most understanding. And also, he wasn’t exactly the strongest: he was always a second tier character, but then again a major superhero.

Rabiroff: I’m interested in this idea of Ben as the Black character on the Fantastic Four. Tell me more about that.

Mosley: When I was a kid, I identified him like a brother. What I would say now is that he’s not like a white American character. People don’t want him around; they’re afraid of him. When he walks into a room, they want to get away from him. When he sits in a restaurant, they say “we don’t have any chairs that will fit you.” His girlfriend has to be blind because if she saw who he really was, that would not work out well. So it’s a thing about being classified a second-class person. Necessary — “I need your strength, I need you to back me up and be there for me” — but also, “you make me nervous.”

Rabiroff: Do you feel like that separates him from the rest of the team? Do they view him the same way as the rest of the world?

Mosley: Well, I feel like he is overly sensitive to people’s responses to him also, which is a thing that you begin to have when you have second-class status. So sometimes he gets mad at them for good reasons, and sometimes he gets mad only because of his own sensitivity.

Rabiroff: So when you approached your own story, how did that kind of inherent tragedy to Ben’s character affect the way you interpreted him?

Mosley: I think his tragedy makes him a great hero. Fantastic Four #25 and #26 outline that pretty well. He’s going to go up against the Hulk. Nobody else would last, but he does. And something it took me years to realize is that in the last panel of #25, he broke his nose. It’s like when Archie Moore fought Rocky Marciano, he lost the fight but he knocked Marciano down. And he bloodied him so bad that Marciano actually quit boxing after that fight. So for me, Ben has made into a great hero despite all of these flaws and limitations, and that’s what I wanted to write about.

Rabiroff: You talk about seeing Ben as a Black character, which is really interesting, especially because these days he’s also a textually Jewish character — and you could argue subtextually Jewish for quite a while before that. You yourself are also a Jewish writer. Was that something that you ever thought about when you were first reading those stories?

Mosley: If I were to think about how Ben is a Jewish character, the first thing is what I said earlier about Ben being a non-white character. And when you think about Kirby and Lee, they were not only Jews, but Jews from New York who had a completely different understanding of literature from DC at that time — where people came in wearing suits and ties, and created characters who all you had to do is change the costume and a little bit of the hair and they’re the same. I think that who Lee and Kirby were and where they came from informed all of Marvel: it doesn’t matter if it’s some Aryan with a big hammer or whatever.

And, look, there were some big flaws with Marvel, too, as far as understanding race, and gender, and culture, and all that stuff. But their road opened onto change whereas in the beginning, at least, DC’s did not. I’m going around it, because I think the Thing can be a hero for anybody. He can be a hero for some Vietnamese kid in Ho Chi Minh City, you know what I’m saying? He represents the social underdog who doesn’t realize how great his power is, but has a big heart. I can share him. He doesn’t need to be just mine.

Rabiroff: There’s an interesting dichotomy in a lot of Fantastic Four stories between the interpersonal family dynamics, and the big, cosmic Jack Kirby ideas: the Kree, and the Skrulls, and Galactus. So what kind of story can we look forward to from you?

Mosley: I think it’s going to start off, like most stories with the Thing, as very pedestrian. The brilliant movement in the beginning of the Fantastic Four was the Yancy Street Gang. They made him an everyday kind of joe, with this gang that kept hectoring him — well, they tried to help him when he fought the Hulk in #25. But it starts there, and goes all the way to the celestial bodies of the universe.

Rabiroff: So you’re going to try to hit all the big genres of Fantastic Four stories?

Mosley: I’m going to try to go through a lot of them. And also Marvel — I mean, you can’t go through the whole history in six issues, so I’m just picking out moments that show what he might do, unexpected villains, expected villains, celestial beings, gods. All that stuff.

Rabiroff: What were some of your favorite Fantastic Four and Marvel stories that were in the back of your head when you were coming up with these ideas?

Mosley: I don’t want to name all of them because it hasn’t come out yet. But I know a lot about the Silver Age of Marvel. So maybe from the time I was 12 to when I was, like, 42 — which is a long time ago now — I read everything. So all of that [informs] how I see the Thing. So when he’s working with the Fantastic Four, he’s the pack animal, carrying all the things they need. I think Ben and Sue are kind of in the same place: they back up the other two. Every so often they get their own thing, but when Sue does, she has to be alone, and when Ben does, he usually turns bad for some reason — at least he did back then. So I just wanted to pull him out. It’s hard to write about a Fantastic Four, because it’s much more familial. Which I like, but I want to talk about the Thing, and how important he is to the whole world: to me, as important as Spider-Man to that world.

Rabiroff: What is his role in the Marvel Universe compared to these other heroes like Spider-Man or Captain America?

Mosley: He’s the kind of character that represents all of us. That’s how I feel: he represents all of us. He has power, yeah, but he’s ugly. He has a great education, but he was raised in the hood and he talks like the hood. He wants to do the right thing, but people are afraid of him. Who we become when we’re asked to represent, to fight for, to believe in — all of those things he brings to the table. And he puts his hands on the table, and the table breaks. And you have to love him for that. And I wanted to represent that love in a difficult way: that at the end of the day, that love is dangerous.

Rabiroff: You’re working with artist Tom Reilly, who I think is one of the most incredible new talents to come along in recent years. How did that come about?

Mosley: It happened in the central circuit board of Marvel. They made a decision and said, “what do you think?” And I said, “great!” And we went from there. And he’s wonderful: his style is interpretive, which I really love. He takes what you give him, and gives it its own voice. And really, comics are much more visual than they are story-driven. They can be story-driven, but the problem is it can’t be too much. A light hand always has to exist when telling a story through a comic book.

I remember seeing a documentary on R. Crumb where he was such a graphomaniac: the figures got smaller and smaller, and the bubbles got bigger and bigger, and it started to be about the language. And the language is not the thing. It’s much more like poetry than it is like novel writing. There’s this moment in Thanos’s history where he’s about to do something really cosmic and somebody says, “excuse me.” And it’s this little girl — his love, Death. And he looks down, and he has this look on his face, and she grabs his finger. And she goes away. And I thought that was brilliant: the least bit of verbal description and a much larger meaning. So I’m very happy to have a talented artistic support that I’m getting.

Rabiroff: Was it a challenge for you to move from writing primarily prose, but also plays and screenplays, into the comic book form?

Mosley: Anything new that you’re writing becomes a challenge. When I started writing for television it was the same thing. Anything that has to do with film, language again is secondary, and what you’re seeing is primary. So, yes, writing comic books is a challenge, but I’m not sure it’s any more of a challenge than anything else is.

For me, I had to figure out the form. So I broke it down first by pages, and then by frames. Because if you and I are in a frame, and I said “look at all those books behind you,” and you go, “what books?” Well, if I’m going to answer you, I have to do it in the next frame. I know it’s a very simple thing, but I had to think about it.

Rabiroff: Yeah, and that’s not something you need to think about in a screenplay, because time just passes as it passes. In a comic you have to be responsible that movement of time for the reader.

Mosley: [In TV or movies] The frames are pushed back into the background and they become meaningless. Same thing in plays. So that’s a difference. The great thing is, in any film — though some of them have seemingly limitless money — you can’t make changes the way you can in comic books. You can’t say, “well I’m in this building, and now I’m in that building.” The people in production say, “look, man, we can’t build that many sets.” In comic books you can do it. So you have some limitations, but on the other hand you have really powerful things that you can do and build. And comic books in many ways have more control of the environment than film does.

Rabiroff: I can’t help but see some similarities between the superhero comic stories that we’re talking about and the genre crime fiction that you’re known for in prose. A character like Easy Rawlins kind of falls into some of the same conventions of superhero comics. Did you feel like there were any similarities or overlaps in the way you approached the two genres?

Mosley: That’s interesting. What it makes me think about is translation: I could make Easy into a comic book. So the short answer is yes — what I do in prose, I do a lot of when writing comic books. But there are powerful differences, and I’m not really sure what those are. The great thing about writing about the Thing is that I know his history. Coming up with a character from scratch — and I’m looking at Kirby and Lee and Ditko — I’m thinking, damn, how did they do that? And I think it’s much easier to translate a comic book into film than it would be into prose, which is why it’s not done so much. It is done, but it’s usually not very good.

Rabiroff: What do you think you might bring to comics as an outsider that writers more embedded in the medium might not have?

Mosley: I don’t have the need to say I’m bringing something to comics that somebody hasn’t brought before. I’m writing about a character that I really like, and that’s enough. And if I do more work, I think I’d develop a voice. But this is a first-time movement for me, so if I bring something that nobody else has, I’d be surprised. I think I’m going to tell a strong enough story that, for me, I’ll be satisfied at the end of it.

Years ago, I’d gotten all these copies of Fantastic Four in really bad condition, #1-100. And I was thinking, “I’m not experiencing this comic book the way I did when I was a kid. What’s wrong? Why I am I not having that experience.” And then it dawned on me: I’m going to scan it into my computer, and I’m going to print every frame out as a full-size page. And when I saw that, I thought, “that’s it.” When I was 12, I could get this close to it. And at this age I’m way out here looking at it, and it’s almost objective rather than subjective.

And I went over to Marvel, and I said, “I want to make a book where each panel is a full page.” And there’s one page that’s a close-up picture of the Mole Man, and it’s just fantastic; I think, equal to Goya. And you know, Goya used to do comics: little political drawings with a caption at the bottom. Hundreds of them, Smith College owns them. So we did it.

Rabiroff: And that was Maximum Fantastic Four.

Mosley: So my love of comic books is very intimate, and it’s my experience. If I can just write a beginning, middle, and end in the arc of these six issues, I’ll be happy.

Rabiroff: But ideally, you’d like to capture some of the way those pages enveloped you when you were 12 years old.

Mosley: Oh, exactly. And it depends more on the penciler than it does on the writer, I think. Hopefully I’ve given [Reilly] a strong enough feeling that he can interpret it. Certainly he has the talent. But, you know, even Jack Kirby if he’s working over at DC, you’re not going to bend in that close, because it’s just some guys in similar uniforms jumping around.

Rabiroff: Well, I don’t know, there’s a real epic grandeur to the New Gods, I think…

Mosley: Oh, no, I’m talking about before ‘62. Challengers of the Unknown; just all these purple costumes, and guys who have to look the same. You could tell that Kirby’s drawing, but there’s still all this, “you have to fit in this box.”

Rabiroff: Last question for you: what are you reading right now, and what might readers of your Thing series want to check out in the prose world?

Mosley: I’m re-reading a science fiction book I wrote called Futureland, because I’m thinking about trying to make it into a television show. I’m reading John Le Carré’s Silverview, the last book he wrote before he died — I love Le Carré’s writing, I think he’s great. And I’m always going back to Gabriel Garcia Marquez. I’ve been reading The General in His Labyrinth.

In terms of comics, for Ben, this is story is something new for him. There’s very little that talks about his past, and the other members of the Fantastic Four are almost non-existent in it. For anybody knows the Marvel Universe, there won’t be much they need to read up on.

Zach Rabiroff edits articles at Comicsxf.com.