I don’t think you should read this until you have finished reading AfterShock’s The Brother of All Men #1, an engrossing beginning to what is sure to be a powerful, horrifying, gripping read. If you have any affinity for cult horror, folk horror or the previous work of the creators, Zac Thompson, Eoin Marron, Mark Englert and Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou, you will likely enjoy this book.

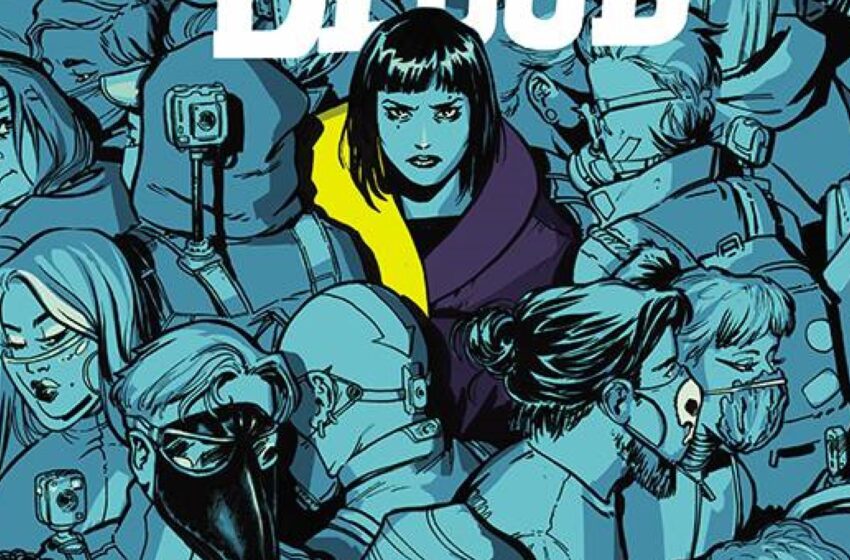

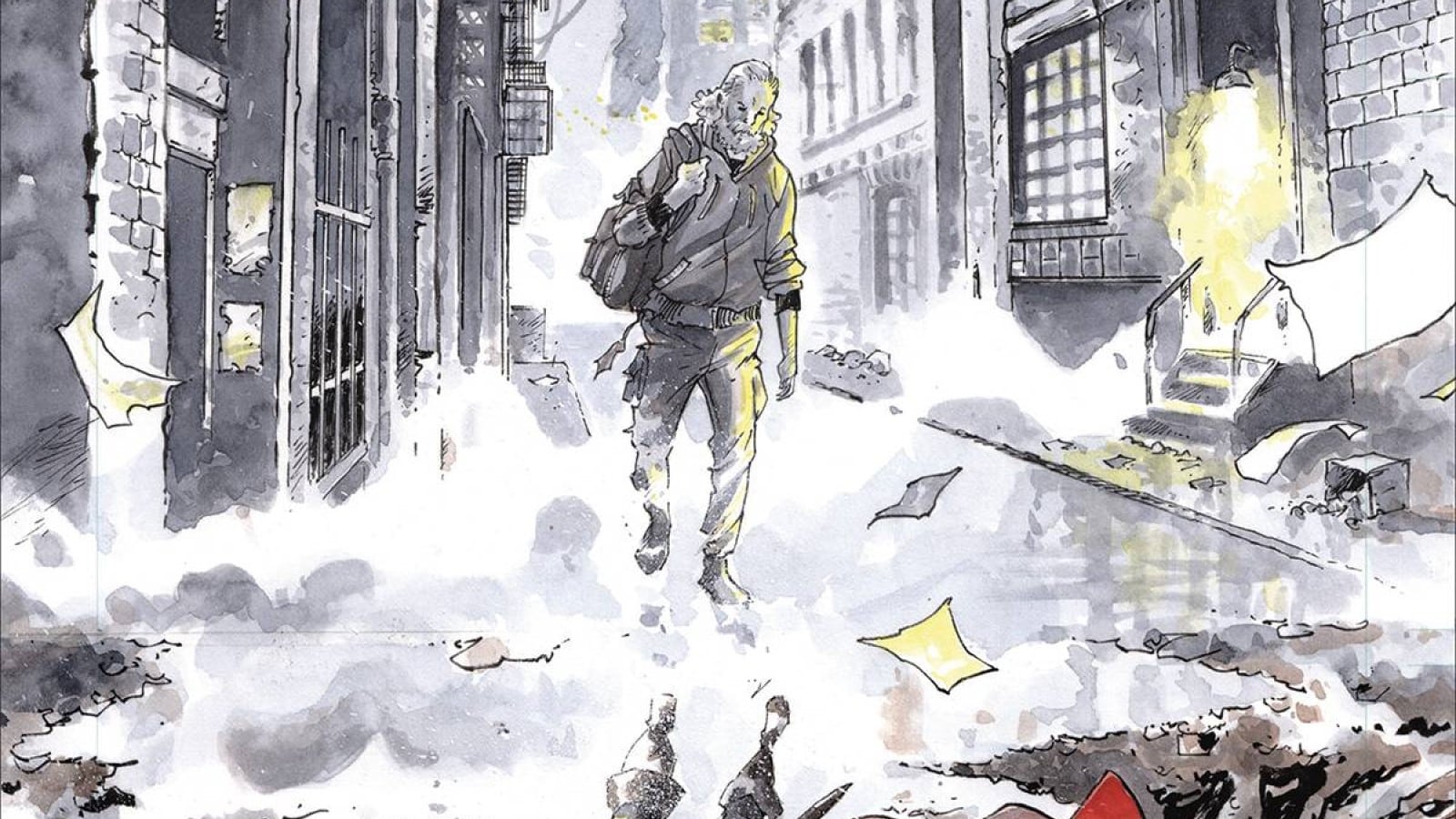

For this first issue, my reflection below was sparked first by the colors. Immediately, on the title page, you’ll see the comic moves from a black-and-white photograph to the Canadian shoreline. Guy Horn steps off a boat into a pallid world. At times it’s blue, at times it’s yellow, but it remains muted, unreal. When he thinks back to the Great War, the images become more muted still. Even his own face is marked by this pale affliction; his eye and surrounding face having been mangled by a sniper, he wears a phantom-like mask. His real eye stares out at the world a deep brown, and his fake is painted a pailer blue, not quite as pale a blue as Victoria often receives, but pale in comparison nonetheless.

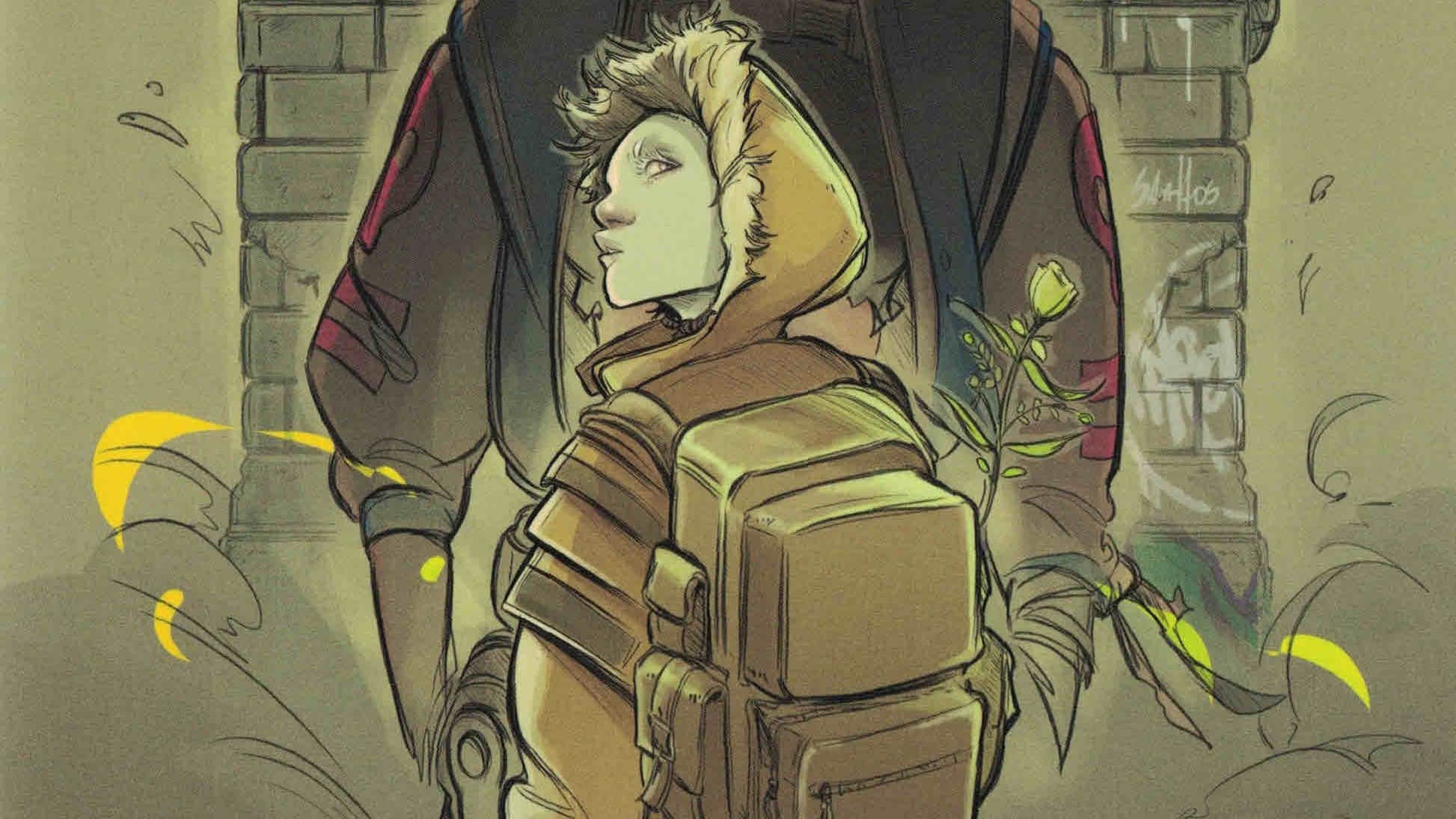

When he first encounters the recruiter, he sees only a sharp black shadow, something that doesn’t seem to belong to the world around it. The shadow gives Guy a map to the cult’s community, “NOT REALLY ME ANYMORE” screaming, unheard, in the graffiti behind him.

As Guy has moved toward this shadow, he has only encountered grime, dirt, disgust. Oil and liquor splash over him; bartenders and priests turn him away; eventually, he is beaten and stabbed.

When the comic cuts to the Aquarian Foundation, however, everything shifts. Englert’s palette is not radically altered, but everything feels deeper. We do not open on a powder-blue sky; instead, we see the purples and reds of sunrise. We see Guy’s brother Bastien, the blond hair gone for ginger, the phantom mask gone for a healthy, full beard. He stares at the ocean across a field of green grass. On the previous page, the wooden buildings of Victoria were almost gray; here you find a maroon fence, an orange-brown boat. You feel like you have passed from a pale imitation of reality into something that is finally, actually real. By the time we reach a stunning, strange vision of the Masters of the White Lodge, we are prepared to accept them; the Masters are not part of the pale shadow that is Canada, but rather of this truer, deeper world. We can understand why Guy might question the reality he knew, his own memory and history, when confronted with not only Bastien’s solidity, there in front of him, but of Bastien’s certainty. Maybe Guy was wrong about Bastien’s death. Maybe Guy was wrong about his own grandfather’s name. We can see that neither of those things feels quite real to Guy anymore.

This is the first thing you should know about cults. If I tell you to picture a cultist, you might think of a gross guy in a weird mask, ready to sacrifice someone in a grungy basement or crypt, chanting in a made-up tongue. We associate cults with the esoteric, bizarre, surreal, but they operate on precisely the opposite principle. A cult can only work if they convince you that it is the outside world that is unreal, if they can convince you that it is within the cult that you can find true reality.

Think of the cults of Wicker Man or Midsommar. These succeed by their ability to contrast the world of the cult with the world outside, a world which feels alienating, bizarre, unknowable, modern. Their protagonists leave behind big cities, academia, the internet, and find communities where each individual is in touch with their world, where each individual is not alienated from the earth beneath their feet but works with it every day. (Brother of All Men is an interesting point of comparison to these not only because it addresses a real cult that historically existed, but also because it takes place at the time, I think, when cults were first able to use this sense of alienation and unreality to recruit followers; it’s a symptom of the early 20th century that only grows exponentially in the wake of the Great War). The sense of reality is given in these cases by alternate ways of living, but also by alternate ways of understanding. Just as modern life is alienating, so too is modern science. I don’t just mean the strange realms of things like physics, how quantum, atomic and cosmic sciences lead to the average person realizing they lived in a strange world that did not operate on the Newtonian principles they witnessed in their day-to-day lives. No, even a seemingly innocuous field like linguistics could unmoor someone; by Guy’s day, one could use linguistics to discover the seams in Genesis, find exactly where someone had stitched together the Bible from different sources. New political ideas and philosophies had swept across the world. In many ways, it’s the same predicament we’re in now. It’s easy to become a Prufrock, feeling that one is always dreaming, always drowning.

I bring up Wicker Man and Midsommar though not only to emphasize the role time plays in cultivating this sense of reality but also beauty. Cults purport to offer truth and goodness, but those take time to articulate; they often win their followers over first with that far more immediate transcendental. I can remember the first time they took us away from our school on a retreat; I can remember the woods, the creek, the mountain. If we entered their minor seminary, they told us, it was even more beautiful, even more incredible. And then, if we became priests, we might be stationed in places like this all over the world. A few years later, they took us to Rome, and a few years after that, New Zealand. Because of those trips, some of the kids I knew back then became ordained; some of the kids I knew back then aren’t around anymore.

You’ll even see this if you go back and watch the tapes that Alison Mack and Keith Reniere produced. NXIVM, like many modern cults, didn’t have a beautiful, centralized compound to mark it as separate from the world, but it emphasized beauty in its public recruiting faces (thus, the emphasis on bringing in hollywood actors and actresses) and in its content (Mack and Reniere often discuss aesthetics, and the goal of many who entered the cult was to improve their own artistic craft). That other famous Hollywood cult, of course, embraced similar tactics long ago.

One of the cult-recruiter’s greatest weapons is beauty, to show you an alternate, enticing world bursting with it. The weapon, of course, works best against those who inhabit a world of ugliness, not just externally, in dirty Victorian streets, but internally. If Guy falls, in future issues, if he is recruited or truly tempted, it will be in large part because he still lives in the blood and shit-soaked trenches, because he will always be living in them. The recruiter knows this; the recruiter targets those who are vulnerable to their weapons.

I look forward to following Guy’s investigation of (or indoctrination to) the White Lodge of the Aquarian Foundation. Again, Brother of All Men promises to be a haunting, thought-provoking series, and I hope to return to this space to reflect on it and on its subject with the release of the next issue.

Until then, remember to be wary of those who offer to show you reality, no matter how beautiful that reality might be.

Robert Secundus is an amateur-angelologist-for-hire.