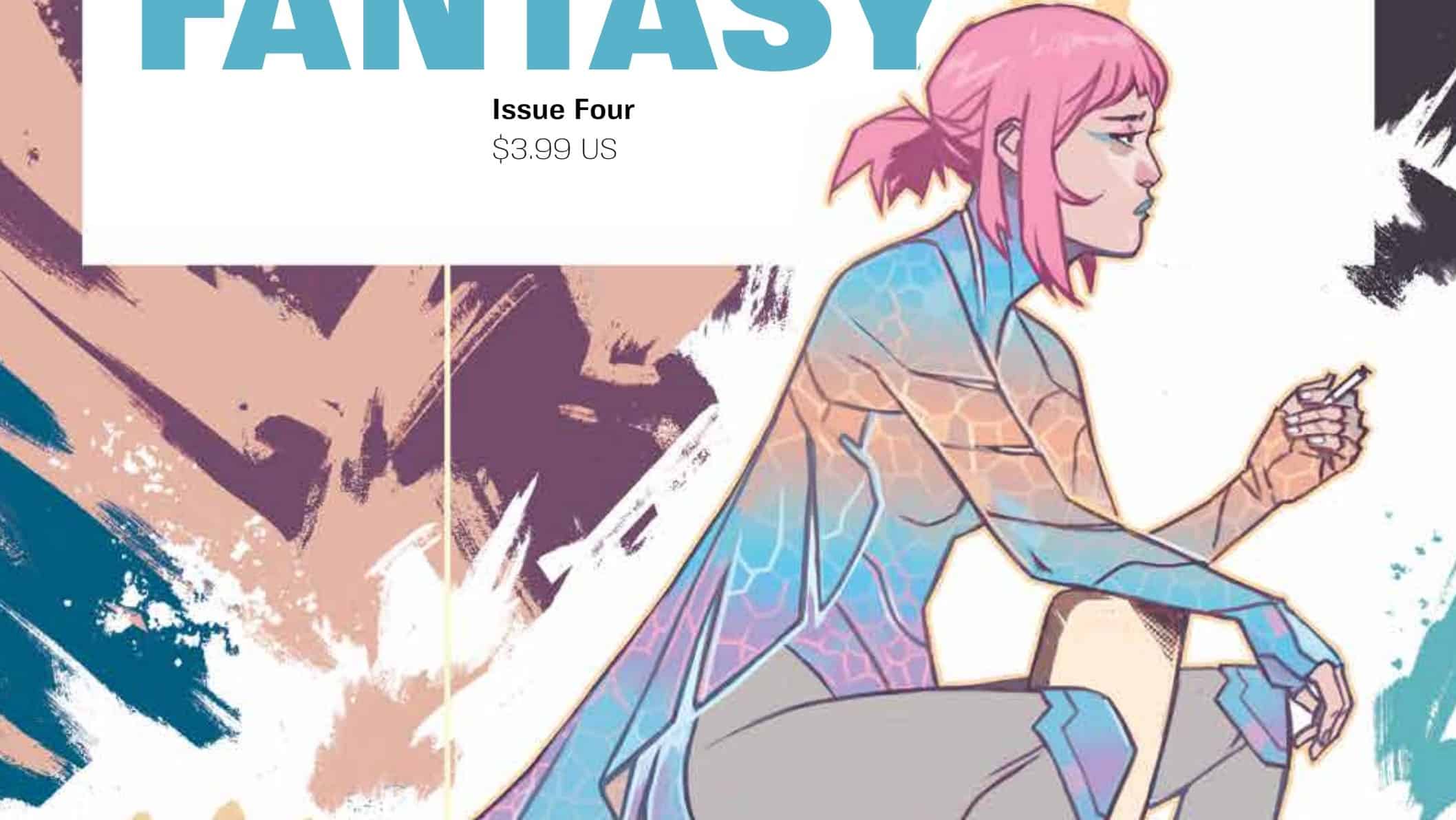

Masumi’s latest art exhibit opens tonight. Tokyo is petrified. Will any critic dare say what they think and risk unleashing her wrath? Meanwhile, Etienne discovers the dangers of long-haul flights when you’ve just murdered a world leader. The Power Fantasy #4 is written by Kieron Gillen, drawn by Caspar Wijngaard, lettered by Clayton Cowles and designed by Rian Hughes for Image Comics.

Sean Dillon: This month, we go to Tokyo and meet the girl who ruined Godzilla for everyone. And honestly, I think this is the best issue yet. This month, I’m joined by Jake Murray. Hi, Jake.

Jake Murray: Hi Sean, hi everyone. Pleasure to be hopping onto the Power Fantasy chat. I trust that everything I say in this review will be received by everyone reading as a piece of transcendent genius. I’ve been working really hard on my emotional regulation recently, and I’d hate for there to be any unintended consequences.

Blood on the Dance Floor, and on the Louis V Carpet

Jake: This issue was the moment The Power Fantasy really reeled me in. While the first three issues have been technically exquisite – and so damn slick – I wasn’t emotionally invested yet. This is where it got more personal, more emotive, more … messy. And exactly what I needed.

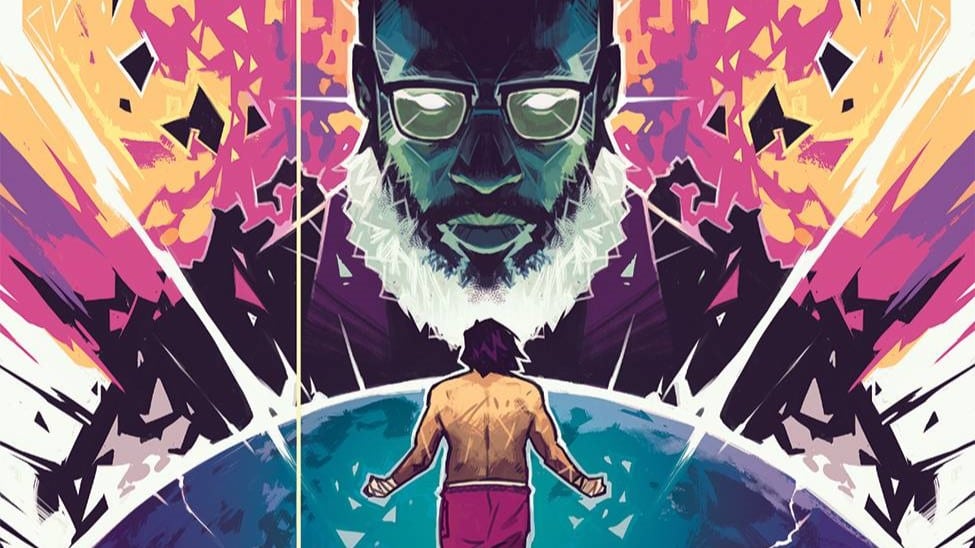

Where the previous issue reckoned with the unimaginable burden of being humanity’s savior from its most self-destructive invention, Kieron Gillen narrows the focus onto the inner conflict that exists within us all in issue #4. While Valentina’s purpose is to counteract humanity’s proclivity for self-destruction, Masumi’s is to almost literally embody it. She’s a symbol of every human’s struggle to cage the beast, taking the form of a depressed artist with the ability to unleash a city-killing kaiju when she gets upset.

It’s of course no coincidence that the fictional universe The Power Fantasy exists in begins with the atom bomb’s first use in warfare. The moment such devastating power was placed in the hands of human beings, the question becomes not about the weapon itself but the people who wield it. Masumi’s story is this existential question turned inward. If a human assumed both roles of weapon and wielder, how fragile would the detente between body and mind be? The answer is: incredibly.

The history of the Cold War is one of escalation driven by mistrust, fear and paranoia. These are pretty much what drives the inner conflict within Masumi, except she’s unfailingly human. Her need for validation, her need for forgiveness and redemption, has given her a complex, which bubbles up within her as the kaiju begins to emerge from the ocean.

There are a few layers expositing this metaphor within the issue, which makes it so on the nose. There’s a good reason for that, though. The metaphor of the monster within is given form by the giant creature lurking at the bottom of the ocean, which is then given further form by Masumi’s artwork. The way Gillen and Wijngaard build this conceit throughout the issue mirrors Masumi’s artistic process: It’s linear, so singularly focused and incredibly on the nose, and it characterizes Masumi brilliantly. You question whether there’s more to her as a character because she and everyone else around her does, too. Her need to express her inner guilt and pain to the world, and for the world to forgive her for it, is so all-consuming that the fate of the world literally relies on her ego being stroked by critics. And how could it not be? Because the truth about her art is too much to bear, and too dangerous for her to discover, she is trapped in a vicious cycle whereby she can never heal, never be more. The consequences are simply too catastrophic. She’s imprisoned in her own guilt, and those she loves and trusts the most, like Isabella and Etienne, are holding the keys.

Wijngaard’s page layouts convey Masumi’s inherent tragedy in a variety of ways. Whether it’s the six-panel grid depicting the escalations and de-escalations of her emotions as the critic climbs up to and back down from the truth over the rising and sinking of the kaiju, or Masumi’s body movements perfectly emulating the monster behind it, the art conveys this pervading sadness so well. Wijngaard’s coloring has a similar effect: Amid the façade of the bright neon art gallery, a darkness lies behind and beneath it, just as it does in Masumi’s artwork.

History Shows Again and Again

Sean: At the same time though, I can’t help but see the limitations here. There are certainly things to appreciate about this book, as you’ve gone into great detail about. But at the same time, it feels a bit flat for me overall.

I think the main reason for this can be seen in the work’s frequent invocations of one of the great works of comics literature, Akira. For many people, Akira is that one really cool anime with the black ball overtaking a city and a really cool bit of animation involving a motorcycle. Narratively, it’s a story about a bunch of psychic kids running around ruins with apocalyptic implications.

On the surface, this feels very similar to the base premise of The Power Fantasy, albeit with some aesthetic differences. But when you dive deeper into the work, the differences become more and more apparent. The key difference being there’s a materiality to the world of Akira that feels lacking in The Power Fantasy. From the opening pages, you can feel the shape and implications of the aftermath of dropping a black orb on Tokyo in 1992 (10 years after Akira was first published and, within the pages of The Power Fantasy, three years after the destruction of all of Europe and some of Asia). The way in which it changed the people of Tokyo both on a technological level and a sociological one. The world feels significantly different from the one we exist in.

Conversely, the aforementioned destruction of all of Europe and some of Asia in The Power Fantasy feels as if it’s a minimal shift in the way the world operates. At most, the Star Wars project Reagan kept hammering on and on about (which itself is another Akira reference) actually happened. But the world feels like the 1990s as we know it. The tensions that haunt the world remain those of the known 20th century.

And that’s even before you get into the changes that would’ve happened due to our superpowered beings even existing. Consider what is arguably the most important work in alternate history superhero fiction, Watchmen. There, we see our masked heroes have an impact on the world stage, be it something small like assassinating two nosy journalists to allow Nixon to get a third term or something larger like winning Vietnam with your giant schlong that shoots lightning. We see how these figures affected the culture in the rise of pirate comics, how technology has geared away from fossil fuels and toward electric cars, and how the world ramped up tensions. There’s a sense of the lived in with how people talk and change.

By contrast, The Power Fantasy is, in many regards, akin to Morishita Masumi’s art. It is not so much concerned with the material world as it is with the giants who stalk around it. This is perhaps more damning when one returns to Akira. Akira, at its heart, centralizes the material, the “glass people” trying to make their way in a world of giants. Many of them are swept up in conspiracies and madness larger than they can actively engage with. They are the children and foot soldiers of the world, not the generals and chessmasters.

There’s a smallness to even the machinations of Tetsuo, arguably the book’s main antagonist. He just wants to feel important, not the second banana to Kaneda. All Kaneda wants is to earn the love of a hot chick and ride his motorcycle while skipping class. In the backdrop of this heated drama between men, you have numerous political factions vying for control, all of them doomed to self destruction or annihilation for their desires.

What Do You Get When You Meet Godzilla and Fall in Love?

Sean: The Power Fantasy, meanwhile, is about the people in control. Those with power stomping on the world so those without cannot. The glass people are secondary to their wants, their desires. The material world matters not when dealing with the issues of giants. And in this, there can be no truth found.

Perhaps tellingly, in the postscript for the issue, Gillen imagines alternatives to The Power Fantasy, ones that reject the operatic for the mundane. And while I would be quite interested in those alternatives, I feel like we’d remain with the limitations therein. If there is no world, then everything will simply float away. Even if you did embrace mundanity, you’d just be making a coffee shop AU. And that’s basically Hell on Earth.

Jake: Let’s talk about the little people then. While, as you say, the story isn’t interested in parochial scenes like, for example, people huddling around a tiny television watching and discussing Superman’s latest rescue mission in a bar in rural Nebraska, it is interested in “normal people” in the context of their relationship with the superpowers. Supporting characters are dragged into the orbit of the story by the superpowers and are defined by their proximity to power and the relative power they hold in that situation. There are two examples of this phenomenon in the issue: art critic Olivia Brown and Masumi’s girlfriend Isabella.

Firstly, fiction’s bravest critic Olivia Brown. I’ve discussed the power she holds over Masumi already, but I’ll mention it again here. It’s the only reason she’s in the story. She’s known only by her reputation, which is given extra weight by Wijngaard’s angular rendering of her austere face, and appears in front of a blank background in every single panel she appears in. Her life, her motivation, even her opinion ultimately, are rendered completely irrelevant. She is only what she represents in this scene. She is only the power that she possesses, and that power is temporary. The fact that in the end her true opinion about Masumi’s art is suppressed by Etienne through mind control is a robust reinforcement of the inevitable nihilism that comes with the realization that an individual’s existence is entirely contingent on the precarious balance of the nuclear deterrent. It’s also reflective of the sense of fear and paranoia that pervaded Cold War America, and seeped into every aspect of human existence including art.

Gillen and Wijngaard have been exploring the power of art throughout the series so far. In a world that’s continued existence is entirely predicated on the whims and wills of individuals, art has the ability not just to reflect it but to shape it in a way that people do not. Valentina listening to The Tornadoes’ Telstar in the previous issue literally changed the landscape of nuclear armaments. Art ostensibly occupies a unique space in this world in that it has power over the superpowers in a way that nothing else does. Despite her immense power, Masumi’s art lacks the ability to change anything because she is incapable of imagining a new paradigm.

Isabella is an interesting case study of the warping and distortive effect of power. She represents the destructive impact of the superpowers both physically (her home country, Italy, was wiped out by a superpowered fight) and in an emotional sense. Her existence as a human being has been entirely superseded by her function as a protector of the world’s safety. To paraphrase Etienne, Isabella’s ironic tragedy is that her function, to lie to Masumi to keep her emotionally regulated, is precisely the reason they will never be in love, but also the reason she can never leave. Gillen’s assessment about the operatic nature of the story should therefore not be confused for lacking a variety of perspectives. Rather than focus on the mundane elements of each person’s existence, The Power Fantasy turns the average person’s existence into a Shakespearean tragedy. The series is interested in not just the Promethean tragedy of playing with the fire of the gods, but the burning effect of its afterglow. Isabella is a great testament to that.

That said, I’ll be watching the repeated beat of Etienne being revealed to have been controlling everything with interest. This type of dynamic can have a flattening effect on the relative power of the rest of the cast, which detracts a little from the stakes of a story. Generally in works of fiction like this though, a character upsetting the balance in this way results in some kind of seismic comeuppance, which feels inevitable where Etienne’s concerned.

Fantasizing About Power

- The art gallery scene is the first time we’ve had more than two of the superpowers assembled together.

- Isabella appears to have tattoos both in the shape of Italy and a Damoclean sword hanging over a bomb impact site.

- Quick call-out for Caspar Wijngaard’s incredible fashion design work in this issue. The art show looks were absolute fire; he also noted the contrast between Isabella’s all black number and the rest of the scene. Great character work.

- It totally looks like Etienne is walking to the art gallery from the airport, right?

- Honestly, I did like the bit with the American. That was at once quite fucked and very interesting.

- Since I have you here, Kieron (and that alt text doth protest too much), I do hope you realize this is all done out of love of the medium and an awareness that you can do better.

- Especially the bonus track.

- In any event, I suppose I should ask … What did you think of Ithaca a Saga?

Ed. note: Tune in to ComicsXF tomorrow for a Power Fantasy bonus track!

Buy The Power Fantasy #4 here. (Disclaimer: As an Amazon Associate, ComicsXF may earn from qualifying purchases.)