The Hulk does battle with Xemnu, a monster that weaponizes nostalgia, in this issue by Al Ewing, Joe Bennett, and Javier Rodríguez.

Zach Rabiroff: Hello there, boys and girls! Remember when you were a kid, living in a two-story suburban house that was always cozy and warm, even in winter time? Remember how your folks used to buy you comics from the ol’ drug store, and you’d all read them together as a family next to a roaring fire? Remember how stories used to be so much better back then? Well, sit right back, because Mr. Secundus and I are here for another installment of Times Immortal, the review column that takes you back to the days when Reagan was president, climate change was a hoax, and Marvel continuity was just plain better. How are you doin’, Rob?

Robert Secundus: I’m in a basement, surrounded by piles of books and comics. I have no place for them; I cannot afford a place for them. I can’t even find them, half the time, underneath all the bills, notices, tax forms. I think under that pile labeled STUDENT LOANS is my trusty old Dante? And under Mastercard– Watchmen? It’s closing in, Zach. It’s all closing in. I can barely see this screen. The payments, the demands, the failures, the foreclosures, the words, the numbers, IT’S ALL CLOSING IN ZACH, IT’S ALL CLOSING IN, I FEEL LIKE MY SOUL IS ABOUT TO BE TERRY GILLIAM’S BRAZIL-ED. But– what’s this? Zach it’s– an ad. A fluffy yeti-thing is telling me to go to Amazon dot com– oh look! it’s a preorder for Masterpiece Tigatron. I loved Tigatron in my youth. I would play with him whenever I went to my cousin’s house. I remember– oh god– I remember– happiness? Maybe if I add this to my cart, I can go back. I can be happy again. It didn’t work for Masterpiece Optimus Primal, or Masterpiece Megatron, or the illegal copyright-infringing Masterpiece Transmetal 2 Megatron. But maybe this time. Thank you, Xemnu. THANK YOU!

Prometheus Ungreened

ZR: This issue’s epigram comes from Prometheus Unbound, a play-in-verse by Percy “We’re Inviting Mary to the Party So I Guess We Have to Invite Him, Too” Shelley:

Thou comest as the

Memory of a dream,

Which now is sad because

It hath been sweet.

In Shelley’s play, these words are spoken by the Oceanid nymph Asia about the coming of Spring. It’s a statement about the pain of nostalgia: the way that the sweetness of something fondly remembered gives way to the pain of knowing it can never come again [Ed. Note: Wait, can gold…stay?]. That’s a theme we’re going to see echoed here throughout this issue, as the Hulk wrestles not only with a fuzzy cyborg alien, but also with the weight of an imagined past. But before I get my professor hat fixed on too tightly (it’s a pirate hat made out of paper), why don’t I pass the mic to a, uh, actual expert. Rob, you have some particular experience in analyzing Shelley, don’t you? What’s your take on this quote?

RS: So, I don’t have extensive thoughts on this passage, because I have always found Prometheus Unbound an utter slog. It’s the Secret Wars II of plays: a languid mire of a sequel to something really excellent and exciting by an utter egomaniac. If I want to read a Romantic closet drama, give me Byron, give me Satan and Cain talkin’ bout murder in SPACE. Anyway, I do think Prometheus makes for an interesting point of comparison with this Hulk. At first they might seem opposed figures: Prometheus creates the human world, either by granting humankind fire or, in some variants of myth, creating human beings themselves. The Devil Hulk is here to destroy that human world. Prometheus ends the most famed version of his story as we have it, Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound, in chains, as we’ve lost the plays in which he was freed. This Hulk, to Roxxon’s dismay, cannot be bound, or at least, not bound by conventional means. But I think closer attention shows them to be of a kind. Prometheus and the Hulk are both Satanic Heroes in the classic Romantic style. They rebel against the order of things, they cause great destruction, but they are moved to do so by a core of great nobility, and something new might be created in the wake of their actions. The enemy of such a hero is tradition, or, to return to your point, nostalgia.

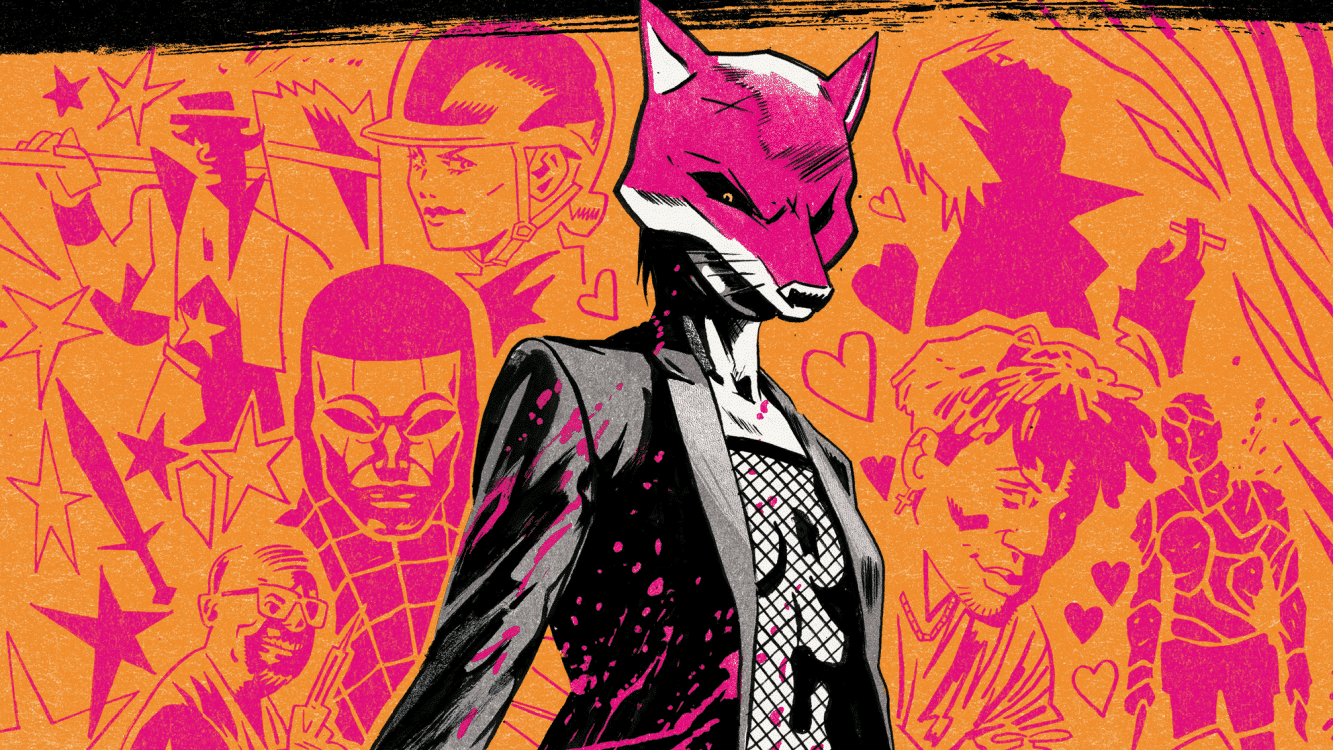

ZR: The key agent of nostalgia here is Xemnu, our adorably terrifying former children’s show host from a planet far, far away. Here, he’s explicitly pedaling a fantasy version of that past history to the public at large. His opening monologue in this issue is like a paean to Eisenhower’s America: “You all know me, don’t you, boys and girls? Xemnu from the Magic Planet? Remember? Before the job and the family you hate? Before everything got so hard? Remember Saturday morning television? The smell of a new plastic toy? Remember being happy? Then you remember me. [Ed. Note: Readers, it’s howdy doody time]”

It’s a fantastic position to put him in, because it stands so much in contrast to the Hulk’s empowering, forward-thinking fight against entrenched interests throughout this series. It’s the very definition of a reactionary worldview: the rejection of the scary, uncertain future in favor of a comforting, childlike past. When William F. Buckley founded the National Review in 1955, he famously wrote that its purpose was to “stand athwart history, yelling Stop.” So of course a corporation like Roxxon would try to undermine Hulk’s progressive battle by turning society toward a vision of their past instead. If they can get the public to fear the world today — to treat it as something monstrous, like the Hulk himself — they’ll seek comfort in the arms of a cyborg teddy bear selling them the fiction of the way things ought to be.

RS: I think you’re absolutely right, but I want to modify your last point slightly: the Hulk also wants the public to see a monstrous world. The real trick the Golden Age conman pulls is in getting you to see the past and present as things in opposition in the first place, to see the present as some unmoored age, cut off from history, rather than the natural extension and result of that past. The radical, now, they see the continuity. They see the same institutions across centuries operating as designed. But without that continuity in vision, the prestige the conman pulls off is incredible: the solution to the monstrous world? Maintain it. By embracing the past, they prevent substantive change to the present. But the radical; they see something that must be broken. They see something that should be smashed.

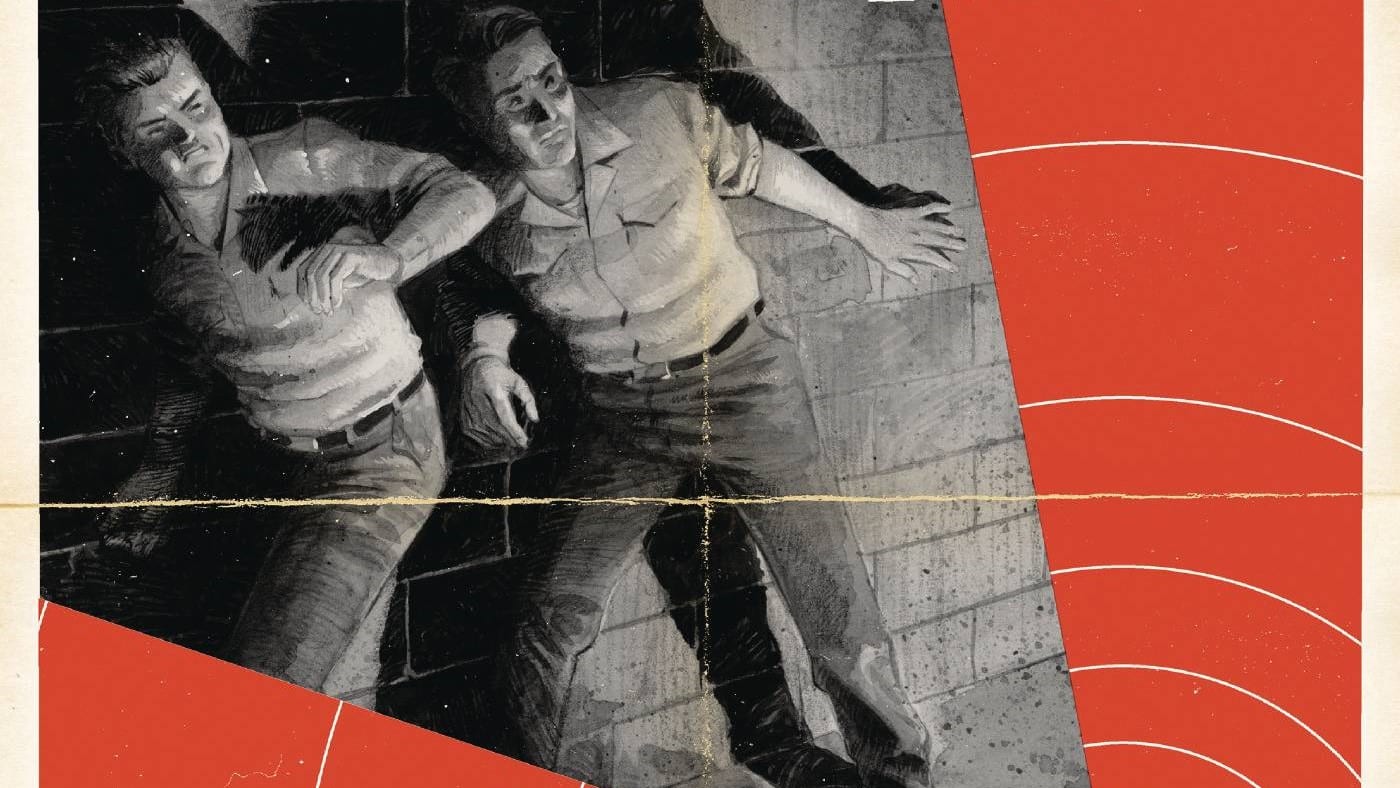

The Devil Hulk’s Walk

ZR: It’s a key point that Xemnu isn’t just exploiting the nostalgic memories of his public, he’s altering and warping them. We see that most directly in the flashback from Charlene McGowan that opens and closes this issue. The first time around, it’s a story of a close encounter with Daredevil, as he busts up an underground drug lab. The second time, it merges surreally with the present, as Xemnu retroactively inserts himself into McGowan’s experience (a trick neatly conveyed by the switch between the clean, retro lines of Javier Rodriguez’s art in the flashback scenes, contrasted with the gritty realism of Joe Bennett’s main story). And we can see Xemnu having the same effect on almost everyone in this issue: Puck, for instance, thinks he was a fan of The Magic Planet when he was a kid, despite being, in point of fact, a 106-year-old Canadian mountain man [Ed Note: That’s likely been retconned but, boy I don’t know where]. It’s the treachery of memory: how the way we think things were becomes weaponized against the way things might someday be. Roxxon’s ultimate victory over the future is to rewrite our history of the past.

RS: What a wacky scifi horror superhero comic! I’m glad that that Dario Agger is fictional [Ed. Note: And not at all like very real people threatening the entire world]!

ZR: Of course, Roxxon isn’t just rewriting the past, they’re selling and commoditizing it. And there’s a really interesting contrast here with the flashback we see from McGowan. In her story, she turns a purely criminal enterprise — selling mutant growth hormone — into an opportunity to undercut exploitative drug prices for hormone replacement therapy. That’s not unlike the way we’ve seen Hulk try to take over his corporate enemies and enlist them in his cause, rather than just smashing them into the ground. And I think that’s the ideological conflict humming underneath this series: Roxxon wants to mobilize the corporate state in defense of entrenched interests and stasis. Banner and McGowan want to mobilize it for freedom. The forces of the system aren’t going away. The question is: are they going to be on the side of the Minotaur, or the side of the Hulk?

It brings me back to Shelley, who described the Prometheus of his play as a kind of heroic Satan, rebelling against the unbreakable laws of the gods, and bringing knowledge to the common man. It’s probably not a coincidence that we see devil imagery popping up across this issue, and this series, especially as one of Banner’s personalities. The Devil Hulk can be violent and unpredictable. But perhaps he can also be a force for good.

RS: Had we started this column earlier, we probably would have written a few thousand words on all the Types of Satans we see in this series and paid particular attention to the Satan of the Book of Job, a Satan that’s not necessarily demonic, a servant of God that’s traditionally framed as a righteous prosecutor, who wields evil and suffering in order to test the virtuous and just. That’s the particular Devil I see in “The Devil Hulk.” But now I’m wondering if the Devil of the Romantics, the Shelley-figure we’ve been talking about today, mightn’t be a better fit. The difference, I think, is in doom. Job’s Satan fails his case, and presumably goes on to try another on another day. But the Romantic Satans, well, they tend to fail, to fall, to be damned. Not all of them– Prometheus is saved– but many.

ZR: While we’re on the subject of selling people the past they want, instead of the future they deserve, I’d be remiss if I didn’t say that this issue could absolutely be an allegory for the nostalgic instincts of the average comic collector. Twitter forgive me, but longing for the comforts of childhood, and violently rejecting deviations from that norm, is kind of the stock in trade for your average internet fan these days. And with a writer like Al Ewing, whose own stories are deeply rooted in old-time continuity even as they push the status quo forward into new territory, I wonder if Xemnu’s lectures are intended as winking references to his, and our, love of Marvel stories of yore. Or maybe that’s just my inner Roy Thomas talking.

Mutability (And Hulk Abilities)

ZR: At the beginning of this issue, we get a subtle, interesting glimpse at Dr. McGowan’s past, as she tells a story of working for the Kingpin’s drug manufacturing empire after being fired from CalTech. She mentions — in a way that’s subtle enough to miss if you’re not looking out for it — having previously synthesized her own HRT as a result of “the growing medical bills, the legal costs, the debt, the stress on top of stress.”

It’s a low-key acknowledgement of trans identity, either on the part of McGowan herself or someone close to her, but it’s an acknowledgement nonetheless. And it’s a reflection of a very real issue in our very non-Marvel-Comics world, where the exploitative cost of HRT creates a serious barrier to trans individuals across the world. Five years ago, Teen Vogue estimated the cost of hormone therapy to be at least $1500 per year: a price very often uncovered by private insurance plans. So McGowan isn’t just trying to turn a buck here: she’s using underground means to help people reclaim their identities from corporate control.

RS: But I think her story shows just how all-powerful, all-controlling that system is. McGowan is working underground, but she’s still working in the employ of a literally fantastically wealthy capitalist who would, if McGowan had been able to institute her plan, profit further off of the suffering of the marginalized. Even when McGowan thinks she’s subverting the system, or using some ill for the greater good, her actions still benefit the monsters who profit off that system. Earlier you framed the Hulk versus Agger as mobilizing the corporate state for oppression or for freedom. What her story suggests is that either approach might still, in the end, simply serve that state.

ZR: That’s a great point, and there’s a real irony in seeing Daredevil’s war against crime actually prevent the public good, albeit inadvertently. Everybody is trapped in the system in their own way, and most of the time they don’t even know it.

Meanwhile, McGowan’s fight also puts her squarely on the side of the Hulk, who memorably defended trans rights earlier in this series. (Well, Joe Fixit did, in any case. But I think we can all agree that Joe is the Hulk persona most likely to be a registered Republican, so if he’s embraced the 21st century, why can’t we?) Hulk, after all, is fighting his own battle to claim ownership over his body and his identity. He’s about inclusivity and humanity for a body that’s been called a monster too many times to count. And if that’s not a vision for a better world, I don’t know what is.

RS: Before we wrap up, I think we need to talk a bit more about the Hulk’s identity and that last page reveal. This series has really mastered the stunning-final-page-turn, but most memorably through revelation of some particularly beautiful or grotesque piece of art. Here the reveal is a simple, single line of dialogue that reveals something that should be chilling. Xemnu has stolen the Hulk’s very name. This is not only, psychologically speaking, deeply violating, a trespass upon identity, but also mythically resonant. Power over names is old magic. With a name one can summon, bind, master, or break. And this isn’t the first attack on the Hulk’s identity Roxxon has launched. Throughout this arc we’ve seen attacks on Hulk’s image, as they trademark his face and sell masks to his followers, corporatizing their rebellion, as well as his reception, or his understanding among the public, in this attack which has reframed the Hulk in the public consciousness not as rebellious anti-hero but as either a wreckless force of nature or a calculating villain. To put it in Roxxon’s terms, with these things, his face, his reception, his name, they now control his Brand.

ZR: I completely agree with this, but I’d add one additional point: I mentioned last time that Xemnu’s name, in his first, pre-Marvel-Age appearance, was The Hulk — a brand he staked out nearly a decade before Bruce Banner hit the scene. So while this might just be a sly wink from Mr. Ewing, and Xemnu may indeed be a cynical accessory to corporate interests, it may also be the case that, from his perspective, he’s not stealing the Banner’s identity so much as reclaiming his own. Repossessing, as it were, the magic planet that should have been his all along.

Marvelous Musings

- The Big Guy has been gaining strength over Banner’s psyche because Xemnu is appealing to Banner’s inner child. But it only works before sunset — kids can’t stay up late, after all.

- It sounds from McGowan’s story like the Kingpin’s response to the HRT-selling plan was…pretty supportive? The mob is profiteering and violent, but they might not be worse than legitimate business every time.

- Dr. McGowan’s Captain America mug in the flashback sequence in colored in the distinctive hues of the transgender flag — a meaningful nod, it seems, from colorist Paul Mounts.

- “Remember how soda used to taste? He’s hurting me very badly.”

Robert Secundus is an amateur-angelologist-for-hire.

Zach Rabiroff works daily at a charity, and is also a freelance writer and editor. He reads a lot of comics.