Welcome to Bonus Reading, a weekly feature in which Matthew Lazorwitz looks at four (or so) comics linked by a common character, creator or theme. Patreon backers of the WMQ&A podcast can request a custom Bonus Reading column built around their fave. Sign up here.

Comics have always been political. Even during the years when the Comics Code Authority neutered comic books, that absence of politics is in itself an endorsement of the status quo. But with the weakening of the code in the 1970s, comics’ social consciousness reawakened, and since then, comics have spoken to social issues with varying degrees of success.

WMQ&A Patreon backer Lan M. asked us to do a Bonus Reading on social issues in comics, so I sat back and had a think. Did I want to do a column based around what the Third Amigo of WMQ&A, Rob Lynch, likes to call “preachy treats,” those wonderful-in-their-way ’80s comics that were given out for free and dealt with a range of social issues? I decided against that, but to instead write about four comics or themes over five decades that tackled social issues in different ways.

The ’70s: Green Lantern/Green Arrow: Hard Travelin’ Heroes

Right at the beginning of mainstream comics’ reawakening to the world outside, there was the recently departed Denny O’Neil. O’Neil was a noted liberal, working those themes into as much of his work as he could. Most famously, along with legendary artist Neal Adams, he took Hal Jordan, the space cop, on a trip across America with O’Neil’s mouthpiece, the ultra-left-wing Green Arrow, for the “Hard Travelin’ Heroes” story.

People who have been reading comics for the past 40 years or so know Oliver Queen, the hero known as Green Arrow, as a loudmouthed liberal, but that wasn’t always the case. Before O’Neil took over the character, he was a simple Batman knockoff. O’Neil took away Oliver’s fortune and had him learn about, and become empathetic to, the fate of the little guy.

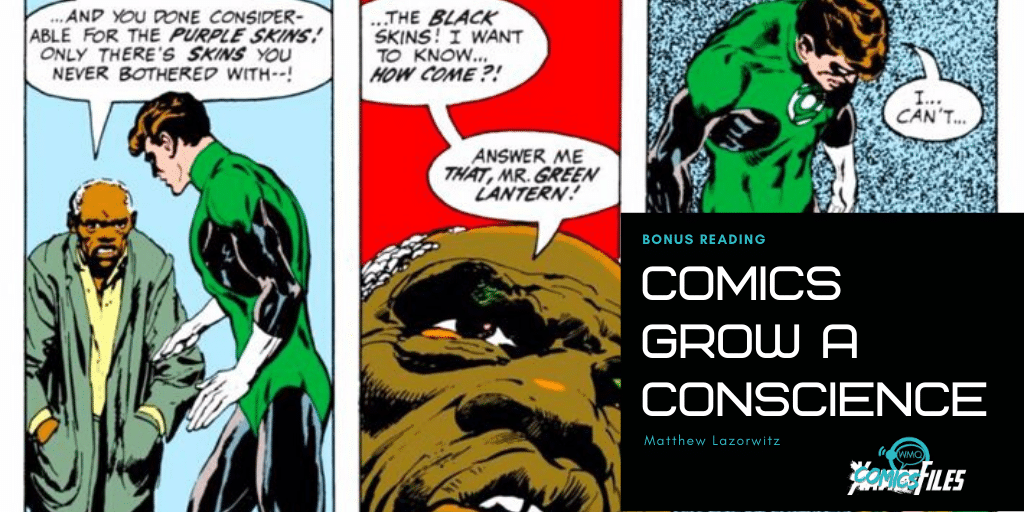

Throughout their run, O’Neil and Adams had Hal and Oliver face villains who weren’t cosmic threats, but ones representative of the ills the writer saw every day in the news. The first issue of the run, “Green Lantern” #76, features an elderly African American man confronting Green Lantern when the hero seems unwilling to help people who are being legally forced from their homes by a slumlord who wants to build a parking lot where the building they live now stands:

“I been readin’ about you,” the man says. “How you work for the blue skins, and how on a planet someplace you helped out the orange skins. And you done considerable for the purple skins. Only there’s skins you never bothered with – the black skins! I want to know how come? Answer me that, Mr. Green Lantern.” It’s clunky and a bit on the nose by modern standards, but for 1972, this was something comic readers hadn’t seen since the early days when Superman fought union busters and corrupt businessmen.

Hal and Oliver travelled across America for 13 issues, and along the way, they fought white supremacists, income inequality, the exploitation of Native Americans and the destruction of the environment for corporate greed. Aside from that first story, though, the most well-remembered sees Green Arrow’s former sidekick, Roy Harper, aka Speedy, deal with his heroin addiction. It’s a painful story, as Green Arrow is confronted by his own failings and leaves Roy with Black Canary to help him detox while raging at the dealers. These stories have aged variably, and some of them have some cringeworthy elements in a 21st century light, but when looking at the history of social conscience in comics, there’s nowhere better to start.

The ’80s: New Mutants #45:

We Were Only Foolin’

When people talk about X-Men comics and how the mutant metaphor often is a flawed parallel for real world minorities, the example that often jumps to mind is the graphic novel “God Loves, Man Kills.” But there’s a smaller, quieter ’80s story that doesn’t get the notice it deserves, one that not only deals with bigotry, but bullying and teen suicide: “New Mutants” #45, subtitled, “We Were Only Foolin’.”

The issue introduces Larry Bodine, a teenager and student at the high school in Salem Center, the town nearest to the Xavier School for Gifted Youngsters. Now, Larry is a new, seemingly normal character given a name and a backstory in a comic written by Chris Claremont. No good of this ever comes. It is revealed that Larry is a mutant, able to sculpt light into beautiful statues, but he is hiding his powers for fear of being bullied or worse by local kids for being a “mutie.”

The New Mutants go to a dance at the high school, and Larry, who has no friends and is bullied mercilessly, befriends the teen mutants and goes back to the mansion with them, but doesn’t make any friends by telling a “mutant” joke. He leaves, and Wolfsbane follows him home, seeing him use his powers. The next morning, she goes to tell the rest of the students Larry is a mutant, when Magneto tells them all that Larry has killed himself. The bullies, not even knowing he was a real mutant, had told him they had called the (not actually) mutant-hunting X-Factor on him, and he chose to take his own life rather than be captured. The others keep Rahne from hunting down and killing the bullies, and the issue ends with Kitty Pryde going to the high school and giving a speech about tolerance and being careful about what you call others.

Claremont, and artists Jackson Guice and Kyle Baker, pack a lot into this issue. You feel for Larry, even when he is being a jerk. This issue uses the trope of someone in the closet who makes jokes about someone else being gay to mask their own identity and insecurities, and the result is tragic, even if the reader has only known Larry for one issue. I also have to say, I’d imagine in the ’80s, when comic readership was more stigmatized, many readers probably understood the pain of being bullied all too well. This is one of at least two occasions where Claremont has Kitty use some pretty offensive language to make a point, though, so be careful on that front.

The ’90s: Milestone Comics

There are plenty of social issues in the comics produced in the ’90s by Milestone, but the story of Milestone itself is one of the most interesting attempts to bring different voices to comics and is a story that should be told more often.

Founded in 1993, Milestone was the brainchild of writer/producer/editor/physicist Dwayne McDuffie, artists Denys Cowan and Michael Davis, and financier Derek T. Dingle, all of whom were African American. The mission of the company was to feature underrepresented minorities in comics. While not all of the creators employed by Milestone were people of color, the ratio was considerably higher than at any other publisher outside the small press at the time. Early work by creators such as ChrisCross, Humberto Ramos, Jamal Igle and J.H. Williams III appeared in Milestone Comics.

Milestone made a deal with DC to distribute their titles without DC editorial interference, although DC reserved the right not to publish content it deemed inappropriate, a clause that would cause friction with the Milestone editors, and McDuffie in particular, at a couple points in the arrangement. While Milestone had the advantage of being published by DC, it began publishing shortly before the comics market crash of the mid-’90s. Coupled with low sales on many titles and a misperception that its comics were solely for a Black audience, Milestone ceased publishing in 1997. There have been a few attempts to resurrect the brand and characters since, including integrating them into the DC Universe, but none of them has been successful, although according to Cowan, another revival is on the horizon.

Of all of Milestone’s characters, the best known is Static, who starred in a successful animated series that ran for four seasons on The WB after the comics stopped publishing. Virgil Hawkins is a geeky teen, somewhat in the Peter Parker mold, who was exposed to a chemical and given electricity powers, Another flagship character was Icon, a Superman-archetype hero, who was of a more conservative mold, and partnered with a rebellious and liberal sidekick, Rocket. “Deathwish” focused on a Punisher-type character who partnered with an openly transgender police detective to hunt a serial killer hunting other transgender people. A favorite character of mine was Xombi, a Korean-American scientist who was exposed to his own nanotech and turned into an immortal “weirdness magnet.”

The ’00s-’10s: The Rise of the Charity Anthology

In the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, various comic book companies got together to release a pair of anthologies to benefit the victims of the attacks, and Marvel released its own benefit magazine called “Heroes.” While these were not the first comics released to benefit a cause (There were titles in the ’80s, such as “X-Men: Heroes for Hope,” that had proceeds going to African famine relief, for instance), these benefit books garnered more attention.

From a publishing standpoint, benefit comics are an interesting project. As they often feature characters from various publishers in one book and stories tying into a very specific event, they are rarely if ever reprinted. They also capture A-list talent, so many fans looking for work from that elusive story from that favorite creator spend years attempting to track these down if they missed them when they were first published. But more importantly, these books send money to those who need it and provide an artistic catharsis for both the creators and the fans who read them.

In the wake of some of the tragedies of the past four years and change, the benefit comic is more prevalent and powerful than ever. Benefit comics have called attention to issues as large as gun violence in America, and as niche as aiding retailers struggling due to pandemic closings. Here is a (not all-inclusive) list of some of the most important and interesting benefit books of the recent past:

“Love is Love” (2016), benefiting the victims of the Pulse nightclub shootings

“Mine” (2017-2018), a Kickstarter anthology benefiting Planned Parenthood

“Where We Live” (2017), benefiting the survivors and victims of the Las Vegas concert shootings

“Ricanstruction” (2018), benefiting hurricane relief in Puerto Rico

“S.O.S.: Support Our Shops” (2020), benefiting comic retailers facing COVID-19 related hardship

Matt Lazorwitz read his first comic at the age of 5. It was Who's Who in the DC Universe #2, featuring characters whose names begin with B, which explains so much about his Batman obsession. He writes about comics he loves, and co-hosts the podcasts BatChat with Matt & Will and The ComicsXF Interview Podcast.