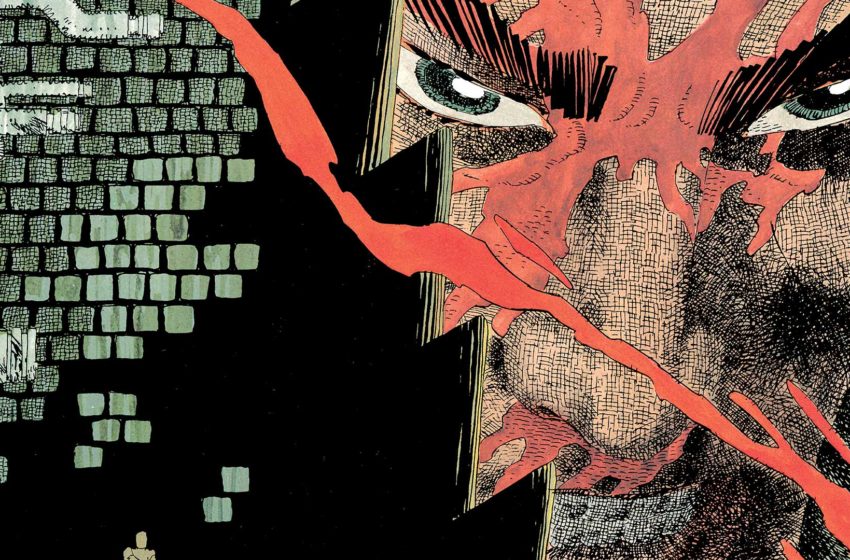

Frank Miller, with his transformative run on Daredevil, the foundational The Dark Knight Returns, and high-profile independent comics-turned-movies like Sin City and 300, has long had an impact and profile to which few other modern comic book creators can compare. The stranglehold of “classic” comic book canon, in the sense of foundational texts, has loosened substantially in recent years, but it’s safe to say that Miller is still one of the big names. As such, he’s been examined and written about as few others have, often highlighting his problematic depictions of women and race, the rightwing politics which run back to some of his earliest stories, and in the 21st century, the intense and inexcusable Islamophobia found in much of his post-9/11 work. A conspicuous gap in the discussion of Frank Miller though, is what I consider to be one of his most notable stories; 1983’s cyberpunk samurai adventure, Ronin.

It’s easy to see why its overlooked, for one thing it’s not Batman or Daredevil, and so its influence on mainstream superhero comics is negligible. The biggest thing to come out of Ronin is Genndy Tartakovsky’s beloved cartoon Samurai Jack, which drew inspiration from Ronin’s opening, where a time-lost samurai warrior finds himself in a future controlled by his shapeshifting demonic enemy. That doesn’t mean Ronin isn’t worth reading though, and putting a critical eye on the story shows, among other things, a uniquely revealing and self-conscious snapshot of Frank Miller as a creative labourer at a major turning point in his career, reflecting on comics, fantasy, and exploitation.

Miller came to the comic book industry in 1979 at just 23 years old, and only a year later he was chosen to take over as the artist on Daredevil. It’s worth remembering that when Miller came to the pages of Daredevil, the character was something of an also-ran. Daredevil was to Spider-Man as Green Arrow is to Batman, a second-tier substitute and never a breakout star, but that changed with Miller’s arrival. His art and influence on the narrative direction hooked readers and soon lead to Miller both writing and drawing the series.

Frank Miller’s first issue as the writer/artist with 1981’s Daredevil #168 is essentially the birth of the character as modern-day readers known him. Miller introduced Elektra and the Hand, reworked the Kingpin and Bullseye, and wrote Daredevil himself as the superheroic posterboy for Catholic guilt whom readers have come to know and love. Miller made Daredevil a star and himself one of the hottest talents in comics. Come 1982, Miller jumped ship to DC Comics where he would eventually, in 1986, complete The Dark Knight Returns, and emerge as the Frank Miller audiences know today. In the time between those two projects Miller was hardly inactive, he was hard at work on what was his most personal project yet. Ronin is why DC managed to poach Miller in the first place, promising him higher quality printing for his new series, increased royalties, and almost unheard of at the time; ownership over the characters and concepts in Ronin. Ronin would be creator owned.

Most North American superhero comics, infamously, are done as work-for-hire deals, meaning that the characters and stories belong to the publisher they are created for rather than the people who create them. Today Frank Miller is much quieter, but Sean Howe’s Marvel Comics: The Untold Story includes several anecdotes highlighting Miller’s vocal advocacy for creators’ rights and his support of Jack Kirby’s legal battles against Marvel Comics in the 1990s, with Miller at one point comparing work-for-hire creators who complained of young stars going independent to “galley slaves complaining that the boat is leaking.” (Howe, 361) This sentiment was no sudden change for Miller, in an interview with Kim Thompson years earlier, Miller admitted that he could have gotten the same perks for Ronin’s publication out of Marvel, moving to DC was about making the point that he was more than a hired hand. From Ronin on out, Frank Miller would be the star.

So then, Ronin. In the late 21st Century, New York City has devolved into a hellish and almost post-apocalyptic state, one of the few remaining structures in the city is the high-tech headquarters of the Aquarius Corporation. There, the psychic Billy Challas, born without limbs and ambiguously defined development issues, is watched over by the artificial intelligence Virgo as he tests out cybernetic limbs and biocircuitry for Aquarius. This routine is broken when Billy experiences a psychic episode and is possessed by the spirit of a disgraced samurai warrior, the titular Ronin, and his body cybernetically augmented to match, just as the Ronin’s demonic enemy Agat arrives to kill him. Escaping into the sewers, Billy’s personality is subsumed by that of the Ronin, who embarks on a violent journey across New York.

Meanwhile at Aquarius, Peter McKenna, the genius scientist behind the biocircuitry which constitutes the Ronin’s body and the mind of his AI caretaker Virgo, realizes that Virgo has been manipulating events according to her own agenda and is murdered by the rogue AI. It is now that the twist at the heart of Ronin emerges: Agat isn’t real, nor is the Ronin himself. Billy Challas was never possessed, he was brainwashed by Virgo into playing out the Ronin fantasy so that she could use his abilities to consume the world with her biocircuitry. Virgo is foiled by the arrival of Casey McKenna, the Ronin/Billy’s love interest and Aquarius’ rogue head of security, who in short order defeats Agat and convinces the Ronin to commit ritual suicide over the shame of being both denied revenge against Agat and saved by a woman. At the final, fatal moment, just before death, Billy’s personality awakens and unleashes a blast of psychic force destroying Virgo, Aquarius, and much of New York City, sparing only Casey, who lies crumpled before a reborn and whole Ronin.

From that truncated summary you may gather that there’s a lot going on in Ronin, and there really is, much of it, unambiguously problematic. Gender and the pursuit of violent masculinity as a route to agency is a major theme, Billy Challas’ Ronin fantasy casts him as a Japanese warrior and sees him subjected to racist epithets and attacks, and Billy’s status as a disabled man is never really examined nor used as anything but an allegory for disempowerment. Looking at Ronin in the context of Miller’s career though, the exploitation of labour bears discussion. Ronin spends a lot of time with two essentially creative workers in Billy Challas and Peter McKenna, and neither is a particularly flattering self-portrait for an artist to write and draw.

Billy’s psychic powers manifest as a kind of wild animating energy, the ability to bring things to life and transform events, but he is trapped by Aquarius. He’s isolated, his disability taken advantage of by first Aquarius and then Virgo. He’s promised that one day he’ll be given independence, but Billy’s power animates Aquarius’ prototypes and it is obvious that they’ll never really let him go. Even when he seems to break free from Aquarius as the Ronin, Billy is still being controlled.

The Ronin is a fantasy, a character from a Japanese children’s show that Billy used to watch, little more than a childish power fantasy he’s being allowed to indulge as he further empowers Virgo, the very manifestation of Aquarius’ greed and the all-consuming project of capital. Miller had been a huge success at Marvel, he’d revitalized Daredevil, turned in Wolverine’s first solo series with Chris Claremont, done all kinds of things, but it wasn’t ever his, it never belonged to him. He has still playing with characters created years ago for children while a publisher made all the money.

In Peter McKenna, we get an even more blunt illustration of creative exploitation. Peter created the biocircuitry at Aquarius; the things Billy animates, Peter built, and yet Peter is disposable. When Peter requests that the biotechnology not be used for military applications he’s brushed off. The allegory ceases to be allegory in the following exchange:

Peter: My agreement – – My contract with Aquarius – – States in certain terms that my biocircuitry will not be used to kill people! […] My biocircuitry will not be used to create munitions. That is all.

Learnid: Eh… that isn’t quite all, Peter. Taggart checked with legal. And legal says that you were contracted for services. Conditional on these services is Aquarius remaining non-military. However, there were no such conditions on what you produced, and Aquarius holds the patent on biocircuitry. So, you see…

Peter: I see. All that I can do is quit. And Aquarius can do whatever it wants…

Peter was contracted for his services, work-for-hire, and so he has no say in what’s done with his creations. Peter’s only recourse is an entirely symbolic and futile resignation, and even then, he is undercut at every turn. When he tries to raise the alarm about Virgo’s true intentions he is labelled unbalanced, locked up, and in a final indignity, reduced to a cybernetic zombie puppet.

As an aside, Alan Moore has for years talked about how he believes DC Comics cheated him out of the rights to Watchmen through tricky contracts, raising important issues around creator rights and ownership. Yet when he comes up in the news its most frequently in the context of provocative snippets from interviews so we can have another round of discourse about Moore being a crazy old curmudgeon who ruins everyone’s fun. By the same note, Jack Kirby publicly feuded with Marvel after his final departure from the company, saying in a 1986 interview with The Comics Journal that “They’ll grab a copyright, they’ll grab a drawing, they’ll grab a script. […] They can act like businessmen. But to me, they’re acting like thugs.” Now that Kirby is safely though dead his name can be proudly displayed on the cover of the latest Eternals reprint in advance of the blockbuster movie, the lovableold king of comics, silent as the grave.

Miller couldn’t have known about those future incidents when he made Ronin, but the writing had been on the wall for a long time in the comic book industry, all the way back to Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster selling the rights to Superman for $130.00, little knowing that their character would spawn an entire genre and make billions of dollars. With Peter’s story Miller writes about the abuses the comic book industry fosters, and has always fostered, in pretty plain terms.

Ronin ends with a massive, four-page foldout explosion as Billy’s unleashed psychic energy destroys the Aquarius compound. Having had the fantasy of the Ronin sabotaged by Casey, Billy’s outburst of pure psychic, animating energy is not only destructive to the world of the story, it pushes the very boundaries of the comic book medium. The standard comic book page can no longer contain Billy, nor Miller himself, and in finally rejecting the control of Virgo and Aquarius, Billy emerges on the other side as his own man. Maybe.

The ending of Ronin is frustratingly indeterminate. The figure who stands before Casey looks like the Ronin, not Billy, and whether it’s Billy in control or the Ronin persona is unclear. By the same token, for all Miller’s dissatisfaction with the way things are in comics, there was no way forward. After Ronin he turned around and did TDKR as work-for-hire, and while he made himself a superstar, he was still doing it for someone else’s gain. It was only years later that Miller would once more venture into creator owned work, like Sin City and 300.

What we get by looking at Ronin as an allegory for creative labour is both a statement of intent for Miller and a portrait of anxiety. Ronin, even before TDKR, is the announcement of the new Frank Miller, the auteur, the visionary, the wild creative force who would play by his own rules and damn anyone who says otherwise. But both readers of Ronin and Miller professionally were left with the question of “What comes next?” Miller would return to work-for-hire for a while longer, Ronin would be a sales flop more adored by critics and fellow professionals than by fans, and years down the line Miller would return to the open arms of first Marvel and then DC Comics.

The industry didn’t change, no single creative outburst could explode the comic book industry the way Billy Challas does Aquarius and New York City. Ronin doesn’t offer easy answers because there are no easy answers to life under capital, but it remains an engaging and shamefully overlooked entry in Frank Miller’s bibliography, a nakedly self-conscious and personal story written by a major figure at a moment of artistic and professional reinvention.