Wanna run away and join the circus? What would you do to get there? And could you live with the consequences? It’s Haha #2, the second installment of the only running anthology series about clowns. Written by W. Maxwell Prince, drawn by Zoe Thorogood, colored by Chris O’Halloran and lettered by Good Old Neon.

Will Nevin: Ari, what do you think about burlesque dancers?

Ari Bard: I can’t say it’s a profession I’ve ever thought much about. I suppose it’s an under-respected and underpaid entertainment profession.

WN: Have I really thought about burlesque dancers before? What a weirdly existential question. Think I’ll have to save it for another day. Now, we’ve got Haha #2, the second installment of W. Maxwell Prince’s *other* anthology series, and I’ve got to say before we get any deeper into it, this issue clicked for me better and harder than the first one. What about you?

AB: I think that this issue was a lot more direct and hard-hitting than the riff on “Bartleby the Scrivener,” but it also felt more familiar, if that makes sense? I felt like I’d seen the story before, possibly in Ice Cream Man or somewhere else, so I think I took more out of the first issue as far as originality goes. That being said, sometimes familiarity is OK, especially when the issue still executes its themes extremely well. I certainly felt a lot more from the issue. I think I enjoyed both for different reasons so far.

WN: Two things on the agenda today: breaking down the story of Rudolph and trying again to figure out what it is exactly we’re reading.

I Have Always Depended on the Kindness of Clowns

WN: Whenever I read Ice Cream Man, I try to decipher what it is I’m supposed to be getting from it — it’s not the sort of book you can passively enjoy (I mean, you can do anything you want with it; read it for the pretty colors for all I care) because it is actively saying something about … well, something, and I always figure it’s my job as a reader — and obviously as a critic — to figure out what both somethings are. Maybe together we can figure out what this issue has to say, but at least for the first half of that riddle, what I got from this was that Prince was shooting for a take on Southern gothic, somewhere over in the general vicinity of Tennessee Williams and his damaged and fragile female characters like Blanche DuBois and Laura Wingfield. Did those notes come up for you, or did something else come to mind in re: what this may or may not be riffing on?

AB: Yeah, I think you’re probably right. I was a lot less focused on identifying what exactly Prince was riffing on than I was with just letting the story sit with me and seeing what I got out of it. Thinking about it now, however, there’s a very Southern gothic sort of generational aspect to this story. It reminds me a lot of something akin to an East of Eden vignette or a snippet from The Devil All the Time for a more recent reference. There was a lot to say about the situations people are exposed to as a child and how we can’t always escape the impact that has on our future and development.

WN: I know I’m coming at this from a bias being a Southerner and all, but I started reading Rudolph’s narration in a drawl and it just worked. I don’t think there was any overt coding aside from “momma” and maybe “daddy” and “doggy” in context, but it made sense to me once it got going. It’s interesting you bring up the generational aspect of the story since that’s what Southern writers seem to key in on, either pain handed down in families or the malaise of bigotry and indifference that settles in on so many places. (As an example of the latter, Jasper, Alabama’s own Jason Aaron is no more Southern than when he writes Southern Bastards, a series that rings incredibly true about what it’s like to live here.) What did Rudolph’s story say to you?

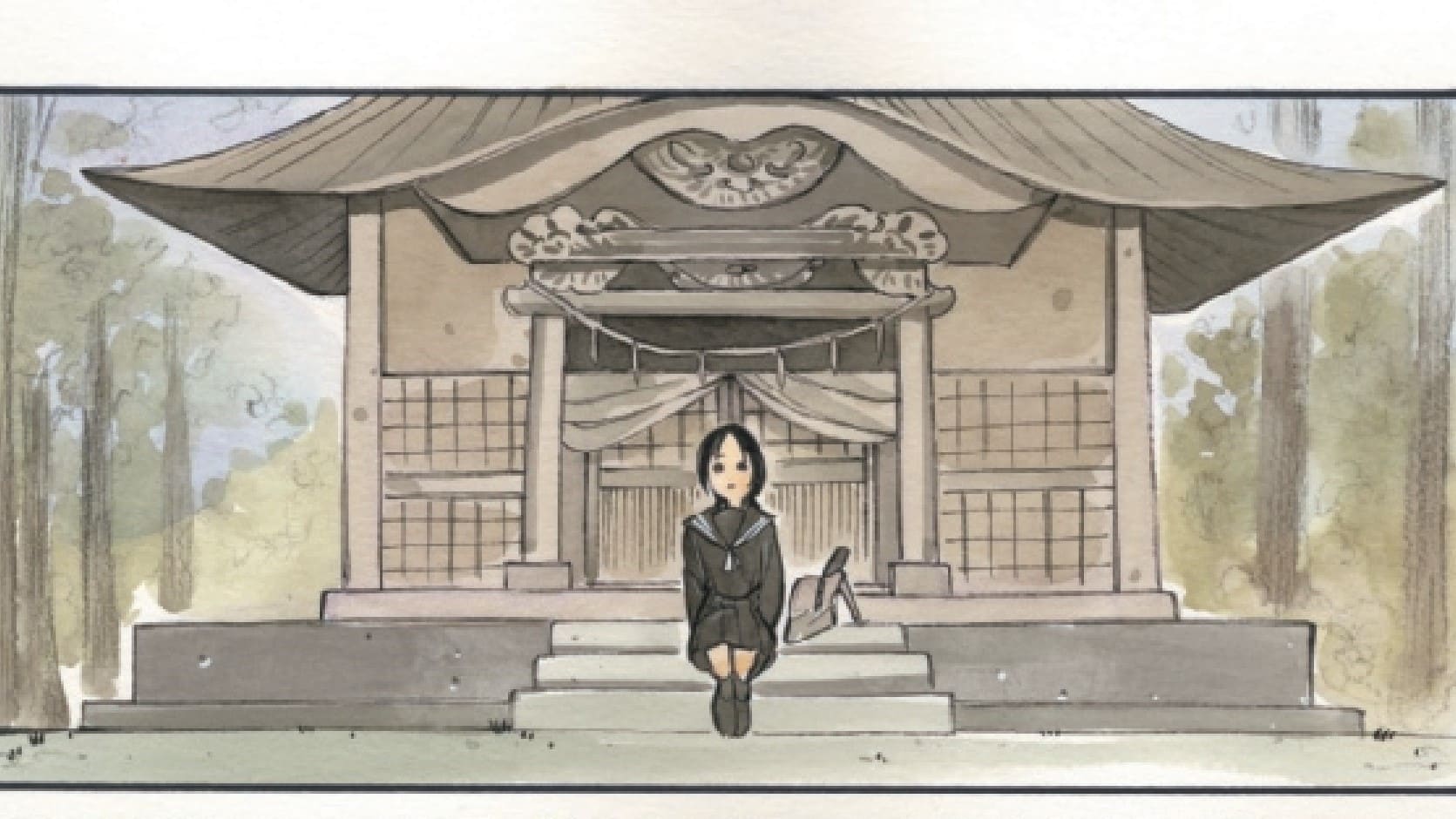

AB: I think the story has a lot to say about parts of our character handed down through families that we can’t escape from. Rudolph’s mother is seen as crazy, and the entire “pilgrimage” is portrayed with a grand sense of frenzy. It’s interesting how much we absorb as children, and I think my favorite part about Zoe Thorogood’s art in this issue is Rudolph’s wide eyes. You can really feel that she’s taking everything in, internalizing it. We can’t help but do so when we’re that age. As we grow up, though, our perspective and curiosity harden, and you can see that with how much smaller Rudolph’s irises are as an adult and how much smaller her mother’s are as well. What continues to strike me, however, is the element of anomaly that plays into this story. Rudolph frames the experiences with the fact that others considered her mother to be having a psychotic break. This is coupled with the fact that she later died from an aneurysm, which I feel is suggested to be related because it’s included. So perhaps it’s not like those Southern gothic tales in the sense that this isn’t a case of generational inheritance. This is an inheritance through exposure, but perhaps it wasn’t innately present in her mom but is in Rudolph herself. What do you think, Will?

WN: This is a dark reflection of the nature vs. nurture question, isn’t it? I believe Rudolph is the way she is because of her parents — maybe specifically her mother — but the question there is whether she’s happy now. (Also, we are all products of our parents, for worse or for better. I’ve seen enough pop psychology shows like Hoarders and Intervention to know that.) She acknowledges that maybe things aren’t quite typical, but she doesn’t seem miserable; she’s taken her mother’s sex work and turned it into something sexualized (although with the burlesque troupe being advertised as a collection of “‘funny’ girls” and “fetish femme fatales” it’s not hard to see her life taking a similar turn). But so long as she has agency in this story? I don’t know that there’s a tragedy for adult Rudolph here.

And since you mentioned the art, let’s go back to Chris O’Halloran’s coloring. We had some quibbles with the thematics of the last issue and how it was colored, but I thought this was spot on, like the sun-faded front room in some Southern home that’s seen better days.

AB: I have to agree. I think O’Halloran’s coloring fits the story and the linework a lot better here. Back to Rudolph and her mother, however, I think it could be a question of nature vs. nurture, and I don’t think there is a tragedy for adult Rudolph, but am very curious about the reflection of nature vs. nurture that this story took, and what the story’s framing says about Rudolph’s mother and society. The issue puts it as, “Momma was smack dab in the middle of a ‘severe psychotic break.’” What I am wondering is, is the mother we see on this adventure who she truly is or is her illness altering her very character? Does it even matter when we’re looking at Rudolph’s perspective? It’s also possible that the whole framing of the psychotic break is simply a way for Rudolph’s father and society at large to rationalize a decision that made her mother happy that most of society just can’t understand.

This Series — What Is It?

WN: We talked last time about trying to find the daylight between ICM and Haha or whether there was any at all to speak of. Do you think we have a clearer sense of that now? If I had to pick out any distinct differences, it seems like the overall narrative is a bit tighter (stories about clowns all having something to do with this amusement park Funville), and that may be about it. The tone is the same — inasmuch as the tone can be consistent between wildly different entries in the same anthology series — and certainly Prince and O’Halloran working together represent a lot of visual continuity even as we have a different artist on each issue.

AB: I think I’m going to need to give it a third issue before I can recognize a pattern or identify any concrete differences, but right now, the stories feel like a tighter version of what we might see in Ice Cream Man, as you said, but not in any damaging way. I think the restrictions on the setting and the clown theme are done to bring out more interesting stories as Prince is essentially doing Ice Cream Man with friends. I’m excited to see what else is in store before I say more.

WN: So guarded! Live a little, Ari. As a fake doctor on television once said, “Pull your pants down, and slide on the ice.” Wildly speculate! It’s the internet. We’re entitled to that.

AB: I suppose you’re right, Will. More on the clown theme, I think that so far, it has added very interesting facets to both issues so far. In Haha #1, “Bartleby the Scrivener” could have been retold with any individual in any profession deciding to reject society, but being a clown elevated that message because in a way, he was living that decision even before he extended it further. Clowns are often seen as choosing happiness and laughter over all of the “real” or “important” things going on in the world in a way that feels like active rejection. In a way, it’s less of a leap. Here in Haha #2, the clown profession is almost what creates the impetus for this story. Rudolph’s father and his friend berate her mother to no end, and it’s likely why she decides to run away to a more promising paradise to start over, and I suppose you could say that being a clown here is a stand-in for any visible, outward-facing choice someone may make that goes against what others might agree with, and I’m not sure there are many other options out there where this story could be told without making it less universal. What do you think, Will?

WN: If #1 was about the rejection of society (oddly timely given that goddamned Snyder Cut trailer), then I think #2 is equal parts an examination of the wages of madness and, as Rudolph puts it, the imaginary luxury of being able to get away from the life you have created and step into a new one. We’re simply stuck with so many things: our families, our talents (or lack thereof), our resources (see last parenthetical). And this is circling back to more directly talk about this issue rather than speculate about what’s to come or the series’ connective tissue, but there is a lot of kink text and subtext in this issue, and I think we’re coming closer and closer to a realization that we shouldn’t shame people for their kinks … unless shame is their kink. (*ba dum dum*)

AB: I think you’re right. And even beyond just kinks as we move into more uncanny realms as well, I think that clowns are something very few can understand and rationalize, and just because that’s the case doesn’t mean that we should shame that choice. Perhaps the connective tissue is the clown profession being a catalyst for choices most of us can’t even fathom, but that doesn’t always mean the person is sick or damaged or less than. If that is the case, then Haha might be a series I can get behind even more than Ice Cream Man.

WN: Maybe we should all be on our way to Funville.

Here’s the Punchline

- I could not figure out the importance of the J.C. Wilber Short Stay hotel. That has to mean something (aside from a reference to a classic cartoon short).

- Clown trivia: The fear of clowns is known as coulrophobia.