Torture, paranoia and the fascist remains of the American state — it’s all just another day in Nuclear Family #3 by writer Stephanie Phillips, artist Tony Shasteen, colorist JD Mettler, letterer Troy Peteri and publisher AfterShock. Based on a short story by Phillip K. Dick.

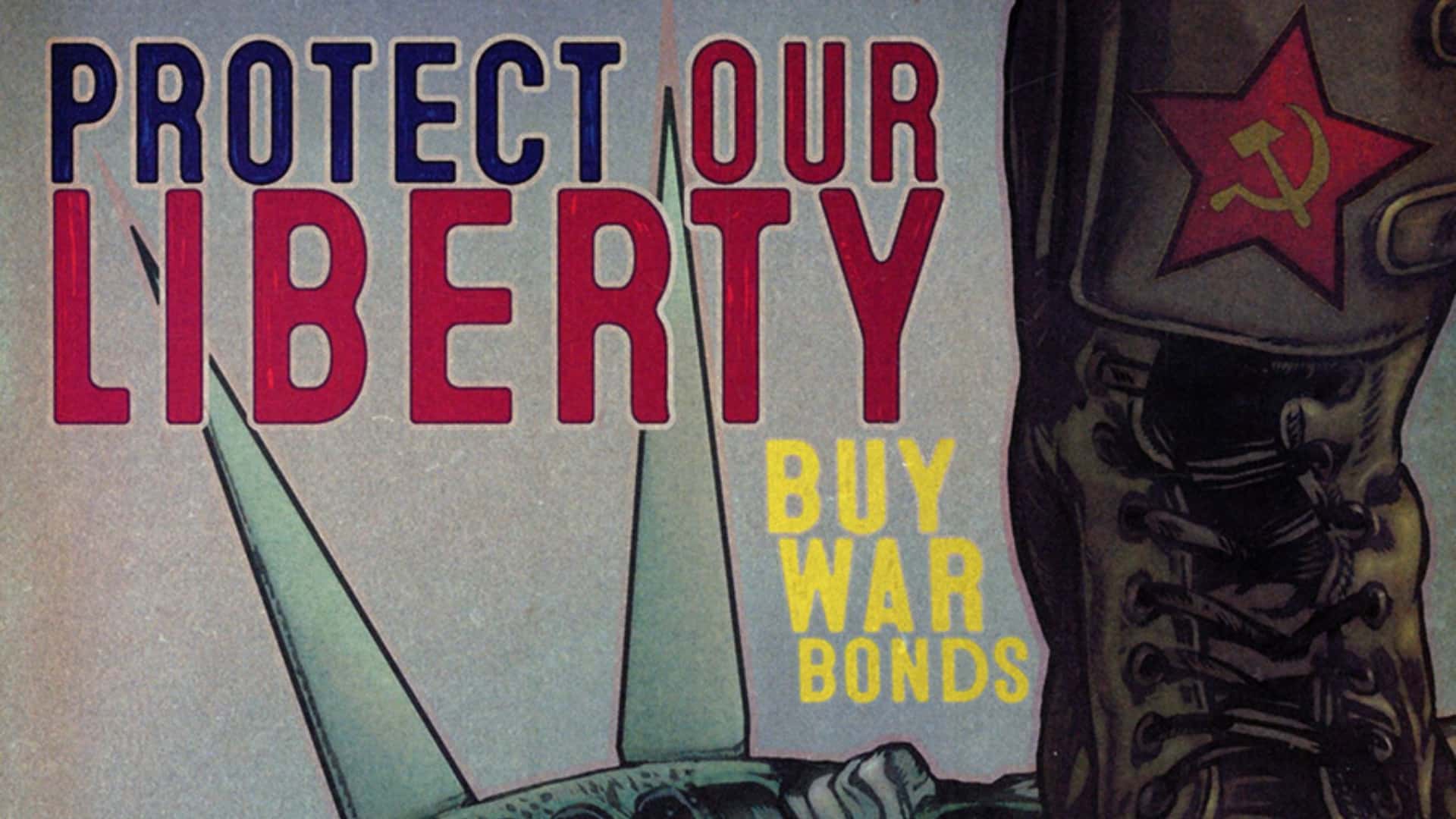

Will Nevin: Since the discussion doesn’t fit neatly anywhere else, let’s do a cold open by talking about the propaganda in Nuclear Family #3. In style and substance, I don’t think it does anything particularly novel. We’ve seen the same aesthetics and sentiment in Fallout. That doesn’t mean I didn’t like it or like it as an introduction to the story. The kids watch a Cold War film with a message that nails the paranoid sentiment running through this whole series: “The only good communist is a dead communist.”

Forrest, I tell my media history students that good propagandists never let on that’s what they’re doing. You gotta be subtle about it. The fascists running what’s left of America? Not all that subtle.

Forrest Hollingsworth: Will, as a pseudo communist myself, I am used to hateful and fearing sentiments. I have to agree that this is of the least subtle variety! Who animates these things? In both form and purpose, it’s meant to be a message for children. I guess on that front it’s hard to disagree with its success. We’ll see that with the adults particularly hawkish actions later. Henry, the toy gun-toting child I admonished in our first column, seems to take the point and its violent implications to heart at least.

Nuclear Family: Keeping children safe since issue Nuclear Family #3…kinda!

WN: Forrest, you’re my favorite pseudo communist.

Let’s Get a Fuckin’ Move On

WN: The bulk of this issue is Robin and Henry, the children of Tim and Linda McClean. They deal with and eventually escape from captivity in this underground industrial bunker complex. So it’s a lot of action and kids in peril — did this work for you?

FH: The espionage feel to a fish out of water story that apes the Cold War is well done. I did find the art a little bit stiff and underwhelming.

Where the homestead setting of the first two issues or the stark contrast of the nuclear wasteland felt appropriately Rockwellian, the action and dialogue here are a little stilted. The visuals are plain and the simplistic rendering over sci-fi backgrounds feels disjointed. It doesn’t feel purposeful.

WN: The kids flail around for a bit. Ok, maybe that’s being too critical, they do alright in their escape. The mysterious Roger bails them out. He’s an older teen-ish guy who shows up for…reasons. Forrest, I don’t trust this fella in the least. Should I?

FH: Roger takes both the kid’s answers that they came from the past and that his mother’s disappearance was because she independently wandered into the wasteland in stride. That makes him either endearingly earnest or completely unreliable.

The reader’s dislike of him based on his otherwise pleasant appearance might have us playing into the same paranoia the book is dissecting, conveniently.

WN: This is definitely a spot where you as a reader of “Breakfast at Twilight” have a leg up on ol’ Will.

FH: Maybe, but maybe not. We get kind of off the rails regarding the source material here. We are still heading towards the same outcome as Dick’s work. The team is clearly trying to add some more modern cultural touchstones and variations to keep things fresh. I guess that’s where we the “inspired by” comes from, huh?

WN: When this thing wraps, we’ll have to chat about the biggest differences between the original text and the series. I hope the changes don’t amount to a Killing Joke-level of tinkering.

Torture Works, Right? (No)

WN: While Robin and Henry are running around, Mom and Dad are not having a fun time at all. Especially Tim who is subject to torture and interrogation. These are powerful scenes, especially after they are reunited. Tim goes silent for a beat after Linda asks if they hurt him. There’s some really nice writing and visual storytelling there. For me, this also spoke to the various communist Cold War-era witch hunts. We were willing and ready to tear other Americans to pieces, ruin lives and careers to find boogeymen who didn’t exist. The more I thought about how Tim did nothing wrong (not that anything can justify torture), the more meaningful these scenes became.

FH: This may fit better in our column about Department of Truth, but it comes back to Illusory Pattern Perception. In the absence of a believable reason for the McClean’s appearance here, the militaristic structure of Sector Twelve (the underground mega-city they find themselves in) demands that they be enemies. This is the fear of otherness at the heart of most fascist structures. It’s also what the Red Scare was predicated on. The book does a middling-to-decent job of accentuating that here. I have hopes they will make the salient points that Dick’s source material does. The miniseries structure admittedly limits that unless the pacing picks up dramatically.

WN: Let’s talk for a second here about how (presumably) Dick frames this in the original story. In our main 1958 timeline, Tim and Dan are..friendly? They’re at least coworkers on good terms even as Dan is willing to lie to move a few extra cars. After the bombs fall, and ten years into an alternate future, Dan is the orchestrator of the family’s torment. Developing this bond, only for the mirror universe Dan to disregard it in the name of paranoia, was no accident.

FH: I think the scene is meant to be sad. In a way it is. Dan’s reticence to recognize the validity of Tim’s history with him is saddening. Especially as the first issue focuses on their friendship. It’s also frustrating, Dan’s solution to the problem being that Tim got that through…what? Communist trickery? Their callousness is entirely illogical, hurtful, and condemning. No option but opposition.

The Exploding Bottom Line

WN: Thumbs up, down, or in the middle — where do ya stand on Nuclear Family #3, Forrest?

FH: There are some pacing and artistic issues that make this one a little less compelling than the first two. I really do appreciate the thought and nuance going into the interpersonal and broader political issues here. At the end of the day, I wouldn’t mind being stuck in a bunker with this book.

WN: On the surface, I think it’s easy to focus on the kids and tearing ass through this bunker complex. When you think deeper about the subtext and the character interplay, this issue is incredibly depressing. Yet, when nuclear annihilation has to take a backseat to personal cruelty, that’s the only thing you can feel.

Living in the Fallout

- The guard didn’t hear Robin jam the lunch tray into the door? They must be playing on the easiest difficulty.

- We’re officially pretending issue #1 didn’t set the series in 1957.