Everything ends, everything begins in the techno-organic hellscape of I Breathed a Body #5 by Zac Thompson, Andy MacDonald, Triona Farrell and Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou.

Robert Secundus: Flesh fades; data dissipates; even languages are someday lost; all is dust. Stories end. And so too, this comic, and our conversations about it. Still, I think, this is going to be a story (and a series of discussions) that lingers in my head for a long, long time.

Zachary Jenkins: I have loved looking into the void with you and seeing what looks back. Let us do so one last time.

[Bramwell]

RS: We learn one thing more of Bramwell before he meets his fate: We see, as we’ve suspected all along, that he’s used the Gelbacut not only to further connect all life, in his ghostly, fungal internet, but to create new life. Mylo was a series of prototypes of fungal children, designed to be sold to grieving parents to replace those they’ve lost. I didn’t think the man could get more ghoulish than last issue, when it was revealed his empire was based on mass-sacrifice, but this attempt to prey upon grief and loss is somehow even more sickening, especially when we see how he’s disposed of the children he’s made, children who are also his end. Zack, what did you think of our final moments with Bramwell, and these final revelations?

ZJ: Well I don’t like Bramwell more, I’ll tell you that. Bramwell is the fungi’s all-consuming nature. He is the innate desire for growth. He is beyond good and evil — the concepts don’t register to him, he simply does what he needs to grow and comes up with justifications for others later. Now, that’s not to say growth is immoral; that drive for growth is natural, it is very literally what mushrooms do; it’s also what cancer does.

In the beautiful horror story tradition of a haught villain being brought down by his own pride, Bramwell meets his end. The discarded Gelbacut children, abominations through no fault of their own, are the ones to dismantle Bramwell’s plot. I Breathed A Body has been about a lot of things, but at the center is an examination of how parents’ failure poisons their children. We see Mylo, or a Mylo, parroting YouTube nothing phrases while gruesome events unfold around him. Call it nature — Bramwell designed him this way — or nurture — Bramwell fostered this behavior — it has roots in bad parenting.

RS: From my interview with Thompson and Horn on No One’s Rose, I know Thompson believes that while — as this series has made starkly clear — algorithms and platforms and videos and all this internet shit do indeed hurt people, do make everything worse, they are not the roots of the problem. The internet amplifies the trauma that precedes it, and in this case, I think the Mylo we’ve come to know and the discarded Mylos we see here are examples of this. Bramwell failed as a parent because he couldn’t see his children as people; his children only became free when they violently seized their own autonomy. It’s a sad, disturbing end for the man, but it also feels just. Then again — should I trust that feeling? Or is feeling positive about that violence and harm being done to someone, is that itself some bad impulse that’s been instilled in me, hell, not just by our media, but by my own not-exactly-100%-constructive upbringing?

ZJ: Listen, I don’t think violence is a good thing, but as Static once said, “Don’t start none, won’t be none.” Bramwell treated life as disposable, and his life was disposed of. It’s the ironic horror beat that works for me here. He had the beautiful ability to connect people through his magical mushroom internet but instead chose to harm as many people as possible. Dude deserved what he had coming.

RS: Death to all capitalists [in Minecraft, of course]. Oh, and speaking of, there’s one more we need to address:

[Zoe]

ZJ: Back when we started this series, we talked about what Zoe wanted: equity in MyCee. She wanted her share in the technology and, in another ironic twist, she ends as the new mushroom matron, the witch queen of the fungal realm. To become this, to save her daughter, she has to give up everything, down to her name. She has become one with the Gelbacut, her memories melded into everyone’s who has ever connected. She is decentralized, something more than human. It’s grotesque and majestic all at once.

RS: On some level, I don’t think she did give up everything — on some strange level she was given everything. Part of her wanted to raise her kid — or just to be the kind of person that would raise a kid — and part of her wanted power, wealth, to be part of the 1%. You can see this as a punishment, or as reward, or as a kind of integration and revelation of who she’s always been. She’s Matron of the Underland, and As Below, So Above — she’s the mother of the Earth. With that position comes power. I think we can probably talk about this ending in terms of a critique of empty, corporate, #GirlBoss white feminism, but we’re probably not the right people to get at anything real substantive there. And if we’re talking about power, wealth and parenthood, my mind goes back to Bramwell, and I wonder — in this issue where their own memories and psyches begin to blend, what’s the difference between the two? Is there a difference? Are we meant to ultimately see them as oppositional figures, or as comparable ones?

ZJ: I would argue that there’s a key difference between the two, and one that changes that #GirlBoss critique. She doesn’t become Bramwell at the end, she becomes the First American unbound. Recall that Bramwell enslaved a force he didn’t understand, razed the natural for the benefit of profit. Bramwell was capitalism, and I don’t think Zoe is.

Notice that we are calling her Zoe, not Anne. Names have power. Anne was the name of the ruthless corporate slave, desperate to be an owner. Zoe was a human, one who made mistakes, but one with a soul. I mentioned that I saw this as majestic, and in a way it is. I saw that last page as Z wrapped in glory. Nature’s victory over technology. It’s stuck with me.

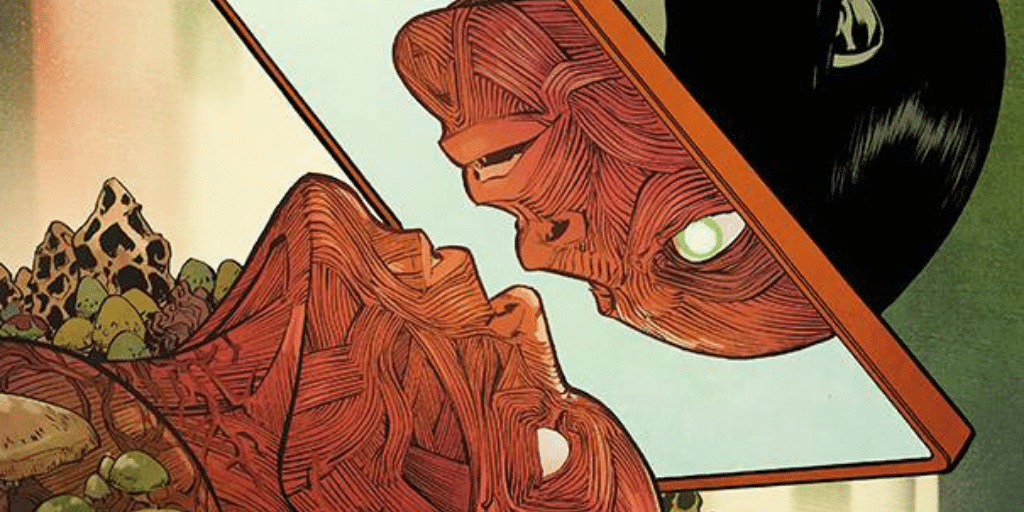

So much credit for that tone needs to be given to Andy MacDonald, who gives an expressive tour de force in this issue. This story has allowed him to ramp up, slowly moving from a lot of talking heads to the carnage and chaos in issue #5. It’s hard to look at in some places, not because it isn’t beautiful, but because there is pain and terror radiating from each panel. Phenomenal.

RS: Last issue, the moments that stuck with me most were the transforming skies and the revelation of the Underland. In this final issue, there are so many panels that will stick with me — the moment when the blended narration just snaps to a close and we’re back in Zoe’s POV, or the moment giant hands crack open her old form like pomegranate and reshape her — I mean, good lord this issue goes hard. And MacDonald’s brilliant work is accompanied by truly excellent stuff from Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou, whose work was vital to that first moment, and Triona Farrell, whose work was vital to the latter. And the final revelation of –Z– is just one of the most haunting sequences I’ve seen in horror comics in a while.

ZJ: I was hard on Otsmane-Elhaou in this series, but that Instagram-ass caption on the final page with the haunting Samuel Beckett quote? Phenomenal work that sums up the entire run in a stunning fashion. It’s about magic and humanity and invisible prisons and connections and the internet and mushrooms and everything.

[All]

RS: We’re going to conclude by talking about the series as a whole. I think we probably have a lot to say — it was a very important series for both of us, I know, a series that resonated on several levels, but I want to start that discussion by beginning with a weird and kind of abstract angle; bear with me for a moment. I want to talk about originality, tradition, allusion and excellence. The most original stories, not just in comics, but in any medium, are often those that allude to, reference or enter into dialogue with previous stories. This is counterintuitive, but if a work doesn’t grapple with its own past, it’s often going to repeat it. Turning to the past, far more than a regurgitation of the past, often allows a work to march forth in the present. This is why so much of my criticism is devoted to intertextual analysis; I think a work is often most interesting as the next step forward in some path begun by others.

Throughout our conversations about this series, we’ve talked about Harlan Ellison, the videos of the Paul Brothers, Annihilation, Hannibal, Arthur C. Clarke, Fae legends, The Social Network, A Dark Song, Saw, Invincible, Midsommar, Swamp Thing, Hart Crane and the Bible, among, I’m sure, others. Some of these points of reference were very explicitly brought up by the series; others we brought to the table ourselves. In this final issue, I found five (I think) explicit allusions:

- Bramwell quotes and cites Isaiah 41:10.

- The blended narrator quotes from Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia, “great things end, small things endure,” though it’s translated as “die” rather than “end” here.

- Zoe evokes the opening of Nabokov’s Lolita (itself a story about the horrors of America, and about a man, like Bramwell, who thinks of himself as a genius but is nothing more than an abusive monster) in her reflection on the sounds and letters of Vedma’s name.

- The name itself of the First American, the romanization of Ведьма, is the Russian word for “witch,” most strongly associated in the English-speaking world with (4A) the Baba Yaga and (4B) Viy, a Gogol novella adapted into the USSR’s first horror movie, a story about an encounter with something that straddles the line between life and death.

- The issue concludes with a final quotation from Beckett’s The Unnamable, the final book in his trilogy of stream-of-consciousness novels, which takes the experiments of the first two further by following what seems to be a lonely mind that exists in void.

And there were also broader lines of influence, such as (1) the revelation that the symbols we’ve seen are collapsed letters of names, collapsed in a way like the sigils of chaos magic as described by Grant Morrison in The Invisibles’ infamous wankathon ad, or (2) the very Hellraiser II introduction of the First American, or (2 again) the very Hellraiser II creation of the new Matron of the Underland (which also, [3] participates in the horrifying trope of replacing-the-prisoner-below that extends back, at least, to Hercules and Atlas).

And I could sit down and start to ask questions like: What’s with all the Russians? What does our reading gain if we start looking at this as a response to Russian literature and Russian horror, especially given that the series seems so concerned with America? Or: Why does Bramwell wear a cross and quote scripture? Or: Is it significant that this series looks to Hellraiser and says, no, we are going to reject these ideas about heaven and hell, pleasure and pain, punishment and puzzle boxes, and instead look to life and death, individuality and connection, material land above and material land below? Or I could miss all these references and ask none of these questions, and still be overwhelmed by all kinds of questions and complications that this series, as it concludes, brings to my mind. I’m sure there’s a ton of stuff — and I don’t just mean allusions or references, I mean thematic undercurrents, complications, questions — that we missed, and yet I don’t feel lost at all, even if I’m aware of my own limits, aware of the gaps in my reading. It is a beautifully haunting, striking, immensely troubling story that confronts us with several horrors of our daily present reality, and it does so by making great use of works of our past, but you don’t need to fully get either that past or that present to find it an incredibly rewarding and powerful experience. That is, I think, the mark of a really profound work of art.

ZJ: One of the core differences between you and I is that you are a well read scholar with many leather-bound books and I have a custom, three-volume collection of the 1995 series X-Man. We are not the same. You came to me and asked if the presentation of Vedma’s name was an allusion to Lolita, a book I have never, and likely will never, read. I knew it was because the passage in question was quoted in the jizz joke comic Sex Criminals. It’s a universal experience with certain bits of art that become ingrained in the collective consciousness. I think of a work of art like Monet’s Nymphéas series and how there are folks who know nothing about impressionism or the techniques Monet brought to popularity, but they know that splotchy water lilies are an art thing.

Good art does that. It takes root in the hearts and minds of society. The learned among us may be able to trace it back to the source, but once an idea blooms like that, the source hardly matters. I say all that to say this, Thompson has not been shy at all about his influences, he constantly talks about them, and I have no damn clue what he’s going on about. I don’t like gross horror movies, I don’t want to watch them. But he’s not going in and ripping off those ideas, he’s taking the bits and pieces that have imprinted on him, and society at large, and crafting them into a universal story. And by that? The book is going to be burrowed in the back of my mind for some time to come.

RS: And we’re talking about universality, but I think we also have to talk about this story personally before we close, not just because, again, it was a story that profoundly resonated with us, but also because that’s been the nature of this conversation these past few months, far more than I expected when we set out. So much resonated with us because, of course, we’re both extremely online. One thing that really became clear with this final issue though, for me, is I really felt this series because of the utter powerlessness it depicts. The kind of despair that creeps up on me these days in the small hours, the kind of anxiety that follows me throughout the day, it increasingly often revolves around powerlessness.

Fungus is pervasive, and fungus is powerful. It extends throughout the forest floor, touching and influencing all kinds of life. It can feed trees, and it can drive animals to suicide. It’s a force in our world that we don’t fully understand, even given this great influence. Maybe despair and anxiety are the wrong words; you know, the classic definition of “the sublime” is an experience of awe and terror in front of something so much larger than yourself that you can’t fit it in your mind. It’s an experience of your own smallness in the face of something that might as well be the infinite. And the experience can be beautiful, but it can also be horrifying; this is a story that uses one force we don’t understand, that pervades an environment we aren’t often in, to look at the forces around us that pervade us: social media, the internet, the capitalists, communication and culture, religion and violence, secret histories and private harms. Especially over the past year — shut in, even more logged on, even more at the whims of these forces than before, waiting to find out if I’d made it on the list of people worthy of a vaccine, checking my email to find out if I had a job or a place to go in the future — I think this series captured the feelings I felt every day better than near anything else I saw or read. I think horror at its best does just that — it doesn’t just reflect the anxiety of an age, it doesn’t just convey something universal, but it opens up a space for the individual to see some reflection of their own feelings, in a dark mirror.

ZJ: I’ve talked a lot about my feelings about social media, parasocial relationships, raising children and my deep, complex relationship with participating in a society that I think we should improve somewhat. We went on long, winding tangents about things wholly disconnected to the text of this comic, because unlike most books out there, this comic weaved itself in and out through deep, relatable issues. A witch will never play a game for my identity, but how I see myself internally vs. how I express myself externally will always be close to my heart. I won’t be asked to livestream the dissection of a body, but my job will force me to make choices I want not to make. I Breathed a Body has an uncanny ability to balance the heightened horror fantasy with the relatable human struggles we all face. It’s the bar more titles should strive to meet.

Stray Thoughts

- As someone who has complained loudly about the oversaturation of the King James translation of the Bible, Rob was happy to see the New International Version employed here.

- Zack bought a page from issue #2 but hasn’t hung it yet.

- Zack also wants to plant a mushroom garden next spring, much to the disappointment of his HOA, who never planned for this.