What’s black, whit and red all – everyone else has already made this joke, right? Deadpool shows his true, highly specific colors in Deadpool: Black, White & Blood #1, featuring stories written by Tom Taylor, Ed Brisson, and James Stokoe, with art by Stokoe, Phil Noto, and Whilce Portacio; colour art by Rachelle Rosenberg; and letters by Stokoe and Joe Sabino.

These days, Deadpool is more of a product than a character. His likeness is a consumable brand; he’s a gimmick that points a story towards unpredictability; he scores points with the ultra-violence types. He’s crude and commercialised and cheap. His malleability and meta-textual functions make him a joke factory, and the quality of those jokes vary wildly, depending on the writer. Deadpool is frequently offensive in the worst way, often overhyped, and on a lot of occasions – especially when he’s separated from his pathos – it all rings hollow.

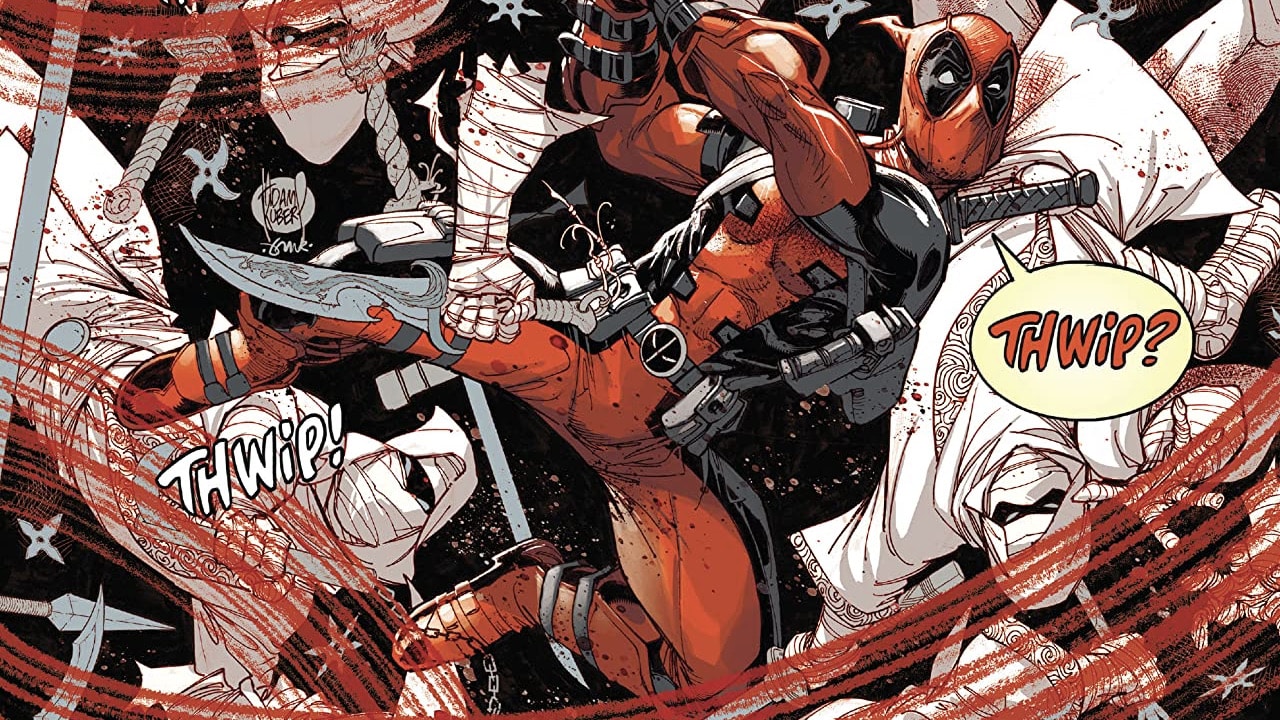

But Deadpool – Wade Wilson – still has rich potential and continuing appeal, and the vignette model of Deadpool: Black, White & Blood #1 might just be the right model for a slight reset: a moment to explore all facets of the Merc with a Mouth, and, later, to reflect on what may become of the sum of these parts. This four-issue series tells its stories in the titular color palette, unleashing a creative visual triptych that on the whole looks arresting, and feels surprisingly urgent. There’s somehow both more and less blood than you would expect.

And that’s a relief. As it is, Deadpool’s best and most compelling traits have nothing to do with his gimmickry, his commodification, or his glamorization tied to hyper-violence (though violence, is, of course, a necessary component of many Deadpool stories). Fabian Nicieza, who scripted Deadpool’s earliest appearances, built him as a direct counterpart to Cable, a throwaway wise-cracking villain who was an instant hit. Nicieza was then instrumental in fleshing him out into a fully-formed character. Wade was unstable, he decided, but his instability had an explanation, and it was grounded in tragedy.

In Domino: Hotshots (2019, captions like a torch song by Gail Simone and art affectingly drawn by David Baldeón) the titular fellow merc, who debuted in the same issue as Deadpool and has been tied to his character in varying ways ever since, thinks: “Everyone I know has a strong reaction to Wade Wilson, mostly unfavorable. Annoyance, dislike, et cetera. But he always makes me think of a broken heart somehow.”

The broken heart. The tears of a clown. The genuine wit with the occasional clarity of a Shakespearean fool. The gloriously drawn fight scenes; the operatic conflicts underpinned by his desire to be seen and loved and known. That’s the sweet spot.

In Deadpool: Black, White & Blood #1, that’s where we open: with the heart.

Tom Taylor pairs with Phil Noto, consummate panel stylist and great humanist (his subjects always seem to have a rich inner life, faces alive with great capacity for thought and feeling), for a story that’s all about connecting with Deadpool’s feelings. Taylor brings back the instant friendship between Wade and Gabby ‘Honey Badger’ Kinney (No one called ‘Scout’ lives at Taylor’s house) that he established in All-New Wolverine (2015). It covers similar ground to that story, but Wade is a character of shortcuts – he’s used symbolically more often than not; he covers old ground time and time again.

Gabby and Wade have a lot in common – both lab-tortured and trained to kill – but Gabby is a beacon of hope whose sunshine-y nature and warmth towards others suggests that we can be better than our worst days. The pair fight a stray zombie-zebra-clone (of course) built by an evil corporation (of course) that Wade calls both a ‘zombiebra’ and ‘undeadbra;’ for Gabby’s sake, he appeals to the villainous mastermind’s sense of reason before he goes for his guts. Wade – and Gabby – know a little something about innocence lost, and here, his attempt to preserve hers speaks to that skerrick of Wade’s soul that still, even now, longs to be redeemed.

Taylor’s earnestness and love of wordplay can spiral towards twee if not unchecked, but they are held in good balance here, his lightness well-grounded by Noto’s sophistication. It’s a light, fresh, and loving start.

Ed Brisson, however, in concert with Whilce Portacio’s now-classic style, heads in another direction. The Bea Arthur direction. Wade’s obsession with the actor has been played for laughs in a sometimes great direction, laced with camp; at other times, it’s been an easy crutch for misogyny disguised as irreverence. This isn’t the worst Bea Arthur joke, but it’s by no means the best: dismayed that the (fictional) 1981 Bea Arthur film Hotline to Heaven isn’t available on any streaming services, he heads out to a VHS/DVD rental store. Cue many dated jokes about the place closing. There isn’t much freshness here, and it takes a moment to adjust – though a couple of lines have a pleasant zing. But the damage is done.

Wade follows the VHS trail to North Valnon, a North Korea analog. Violence, naturally, ensues. Rachelle Rosenberg’s colours are carefully deployed, but the story barely hangs together. It all feels a bit forced – the old pop culture references, the lazy evil dictator angle – that it just doesn’t reach the breezy, pop-culture cheery heights at which it seems to aim. Oh, the evil guy loves Bea Arthur too? Hasn’t she been through enough?! A fuller picture of the issue begins to form, and its scope reveals the limits of Deadpool’s elasticity – stretch him too thin, and he won’t always bounce back.

James Stokoe, however, has recovered the bounce. He rounds out the issue with a gleeful story that embraces Wade’s cartoonishness. He has Wade seeking out Arkady “Omega Red” Rossovich (who texts: ‘STARTED MY OWN COUNTRY LOL’) over pages that have deeply embraced the ‘blood’ section of the color palette, with red-washed skies and cheerful details that feel full of life and movement. Arkady, proudly, embraces his ‘tiny raspberry boy’. Stokoe’s art is sometimes delightfully off-kilter, and color is an important factor here; he creates an atmosphere that has a sense of humour, a playful unreality.

With this story, the fog lifts and is replaced by an easy, unhurried fun. By exaggerating and lovingly spoofing these so-recognisable characters (Omega Red’s ego is enormous; a well-deployed cutaway leads to a clever Alpha Flight reference, and Ursa Major is there), Stokoe finds his way back to Wade’s appeal as a narrative-bending player on the Marvel comics bench: if you foreground joy and bring your readers into the joke, rather than aiming at them, it’s a pleasure to be in Deadpool mode. Especially here, as he plays straight man to good old Arkady to great effect.

So who is Deadpool in 2021? According to this first issue of Black, White & Blood, he’s deadly, sometimes funny, a little tiresome, outdated, a little wry, a little loving. A little of a lot of things, with a lot of room to grow.

Cassie is an arts and culture writer living on Gadigal land in Australia. For 10 years she’s been working as a professional theatre critic, and is delighted to finally be writing about her other love: comics, baby.