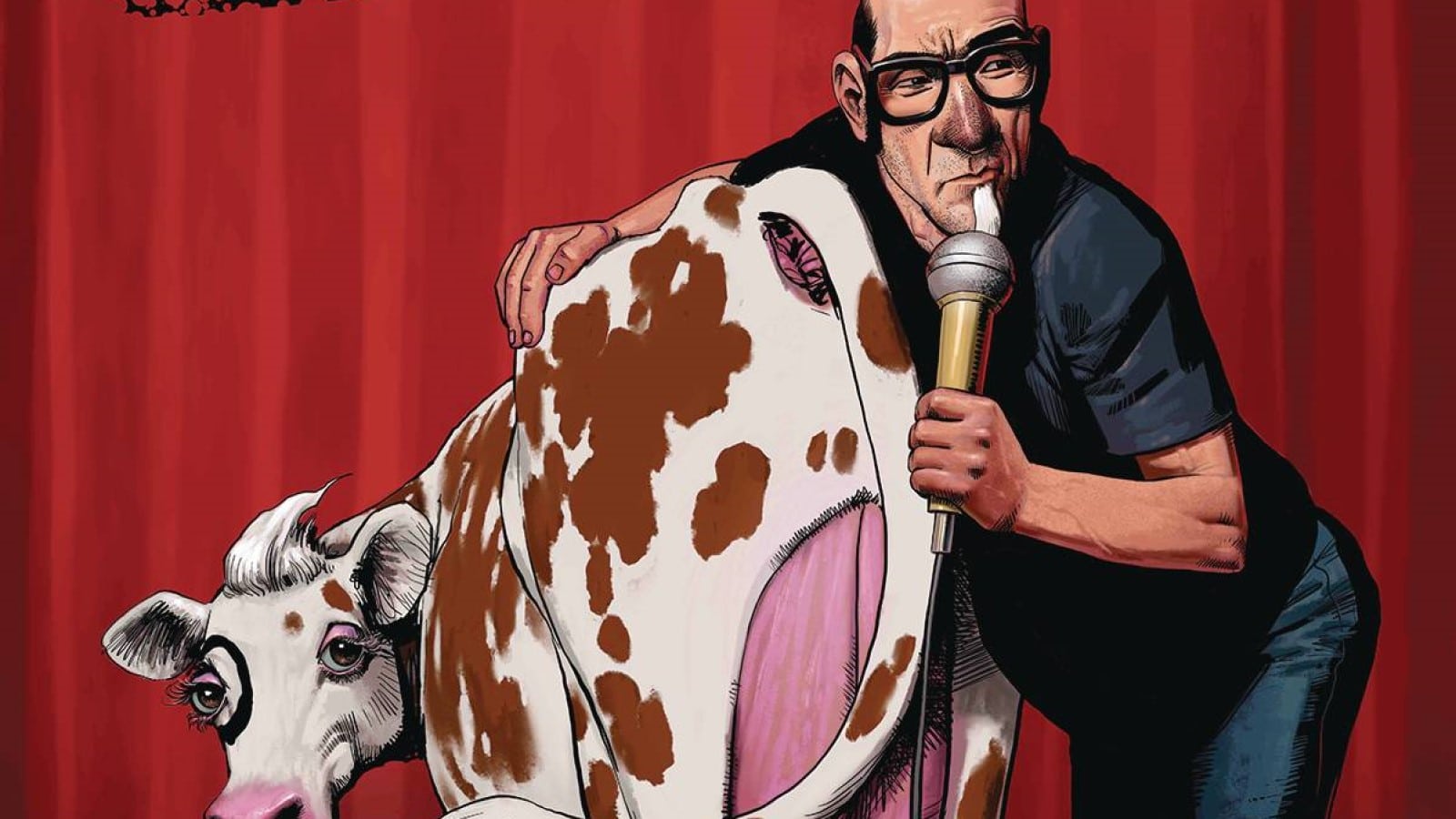

What if we excavated a tired, white ‘90s comedian and sent him on tour with some fresher voices only for him to melt down on stage and lean into the “cancel culture” brain rot infecting entirely too many people? Meet Melville Snelson. He sucks, on stage and off it, in AHOY Comics’ Snelson: Comedy is Dying #1, written by Paul Constant, drawn by Fred Harper, colored by Lee Loughridge and lettered by Rob Steen.

Will Nevin: Snelson is a book about stand-up comedy, so let’s start there — who are some of your favorite acts in the medium?

Cassie Tongue: One of the best things about becoming a stand-up fan in the ’90s is being one now, because the evolution and expansion of the field has brought me some of my greatest joys. I’ll always love an erudite storyteller like John Mulaney, but that’s like saying I love sunsets or puppies; hard to argue with a good thing. I get so much joy now from comics like Julio Torres (My Favorite Shapes is a masterpiece), Joel Kim Booster, Rhys Nicholson, Jaboukie Young-White, Emmy Blotnick, Gary Gulman (State abbreviations? Trader Joe’s? Sir, I’m trying to catch a breath), Hannibal Buress, Anne Edmonds and Steph Tisdell (I’m Australian, they’re Australian and hilarious), but my comedy sweet spot is Zoe Coombs Marr, who blends absurdity and meta-comedy with dazzling results (like the time she toured as “Dave,” your typical bloke-comic whose inner clown identity, unlocked at clowning school, is a cranky lesbian named Zoe). I could keep going; heroically I will not. Who do you love?

Will: This is exactly the contrast I was hoping for. You’ve got so many hip, cool names up there (Man, did Hannibal Buress ever blow up with his “Hey, Bill Cosby is actually a piece of shit” joke that was not a joke), and my tastes — owing to my late father — are decidedly old. George Carlin, specifically the cranky version. Lewis Black (one of dad’s favorites). Bill Hicks is cliche, but at least I picked that one up on my own. Now, let’s go in the opposite direction. Who are the people you can’t stand?

Cassie: I fell hard for joke craft while listening to Comedy Central Presents sets over and over, so naturally I’ve developed an aversion to any brand of hypermasculine, “take-my-wife-please,” ego-forward comedy. No sense in naming names here — it’s more an archetype than a person (Most guys in flannel aren’t Shane Torres defending Guy Fieri), but it’s also, of course, the exact archetype at the heart of Snelson. Which makes it an interesting read. You wanna name some names, Will?

Will: I’ve got a name that maybe we could both agree on that’s not great: Bill Burr. [Grote’s note: PREACH!] I don’t think he brings a lot to the table in terms of delivery or material, and yet he’s everywhere. Why? We’ve got our top men working on the answer to that one.

In reading the logline and getting a sense of the series before I actually read the first issue (I landed at something like, “aggrieved ’90s comedian rages against the dying of his spotlight”), I imagined a guy like David Cross — someone who, like Burr, never seemed to be that funny but was still always on the periphery of fame and superstardom. He also traded in and defended racist schtick as recently as last year. After reading Snelson #1, I think this *is* Cross — or at least someone who shares most of the same values (or lack thereof) and gripes.

Cassie: There’s absolutely a lot of Cross to our, uh, star, but what’s more interesting to me, I think, is how much Snelson represents an entire constellation of comics who are moving out to their own spaces, opening their own comedy clubs, lashing out at the comedy world that has rejected them for the harm they’ve caused. If we were going to list names, this piece would be extremely long — and extremely depressing — and largely triggering (Want to really dig into it? Read Seth Simons’ fantastic newsletter, Humorism). What’s interesting about Snelson (and honestly may prove difficult to read) is how on-point he is as a satire. Every angry, self-pitying, insecure, upsetting trait is here on display.

Melville’s Just a Giant (Moby) Dick

Will: Snelson, in just 20 pages, stands out as an inherently pathetic character, one who got at least a *little* pity from me. And I have to think his first name — Melville — is no coincidence as a nod to Moby-Dick author Herman, who died in relative obscurity after retiring from writing because no one wanted to read his work. What did you think of the character and how he’s framed here?

Cassie: I felt no pity for him, gotta say! I appreciate that Constant is writing this guy not to be glamorised but also not without depth — and there’s a single panel where Snelson is listening to a voicemail, and in his countenance artist Fred Harper has stripped away the comedian’s performance to present him as something honest and real, like green shoots peeking through dead leaves — but I never warm to him, and I’m glad that I don’t. The interesting thing about Snelson is that the thing he’s raging against, being deplatformed, hasn’t, of course, deprived him from speaking out. He’s still speaking. He’s still performing. Maybe not to his old, dizzying, used-to-kinda-know-Janeane-Garofalo-so-how-bad-can-he-be-really heights, but he’s still there. Of course he is. Cancellations rarely stick.

The Melville nod is an interesting one, because — particularly in Moby-Dick — his brilliance lay in paragraphing, chaptering and phrase. Shapes of hyper-feeling, drawn from lived experience, to create momentum and mood? It’s not so far from the craft of comedy. But what makes it more interesting was Melville’s response to the world’s seemingly unified response to his work (which was never really a dismissal, and never really that unified). He made what John Updike called a “soft withdrawal” — shifting from the hugely ambitious Moby-Dick and from novel writing into short stories and poetry. He was not received as he liked, so he shifted, evolved and adapted so he could keep doing the thing he loved most: writing. Sure, sometimes he was stubborn and aggressive. Sometimes he railed against the world. But there’s something redemptive in being willing to change and shift with the times, with the society around you. That one way he tried to connect wasn’t working; he found others; he did the work. Snelson has no such grace, at least not in this issue.

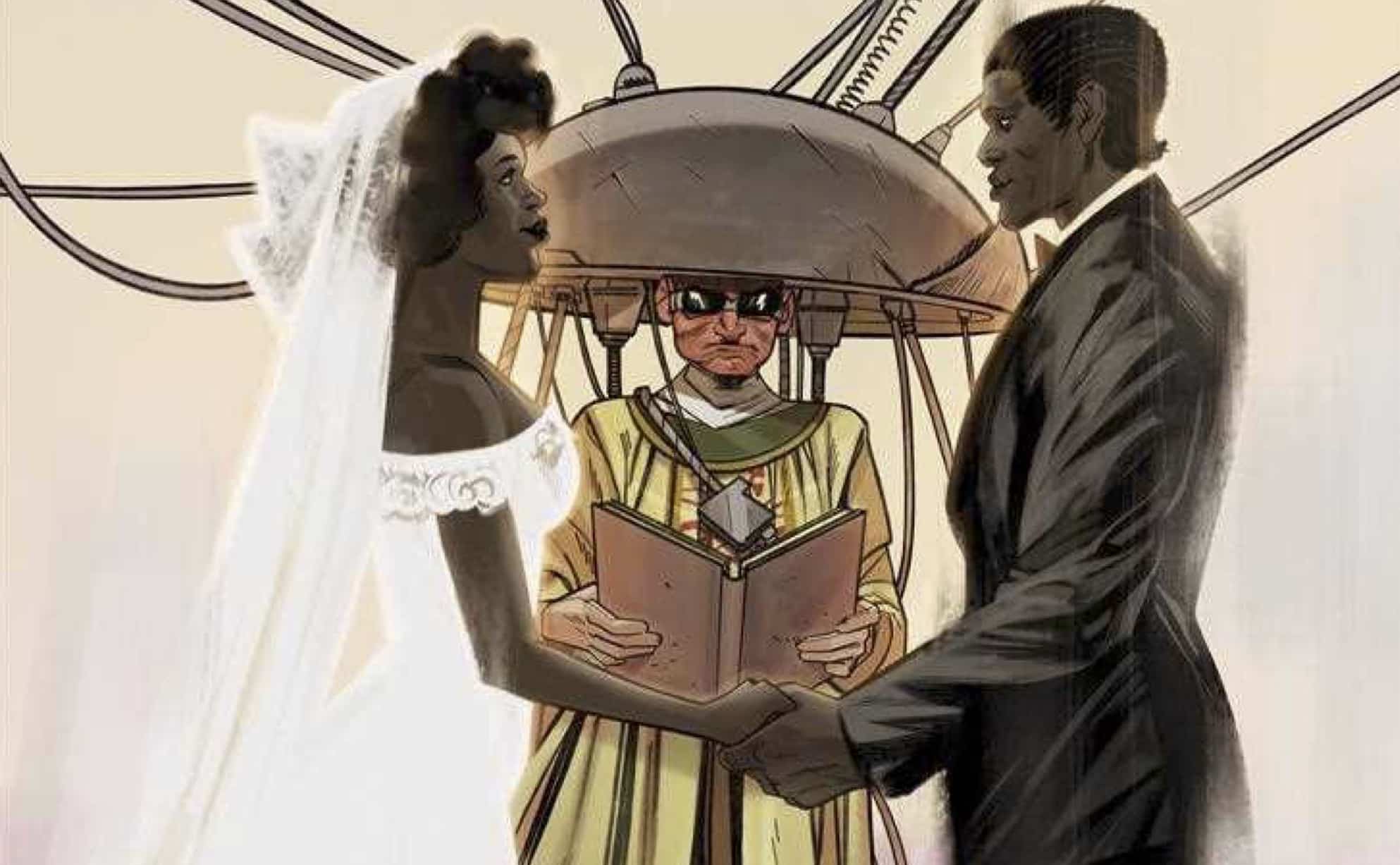

Will: I think the pivot from this first issue to the rest of the series is going to be interesting because we get at least some sense that Snelson is banking his career on the “human shields” of “a vegan Jew, a giant Black dude and a trans woman.” You get the feeling that at some point in this series, he’s going to pull a Tucker Carlson and start raging against “identity politics.”

Cassie: Yes, it feels inevitable that he’s going to spiral in a particularly familiar way. We can see this shift in him begin in this issue after something happens in his personal life that he wasn’t quite prepared for; he’s taking his personal problems and pushing them outward, lashing out in response. What will that mean for the rest of the comics on the “Get Woke or Die Broke” tour? It’s a little too early to tell. What’s your take on this tour situation? How did you feel after you read the book?

Will: Within the universe that Constant has created, it feels incredibly exploitative — which I think is the point. Snelson has chained himself to this bunch that actually has a future, whereas he only has a past that never amounted to much. Yet it has the air of symbiosis since they get the benefit of touring with someone who people may sort of remember and be inclined to check out for the hell of it — like if Marcy Playground was doing a gig at your local amphitheater. I’m hoping we get a flashback or two of a really desperate Snelson trying to pull this tour together and convince the gang he’s not an inveterate scumbag.

In the “real world,” though, I don’t think there’s any way a tour like this would work — would people pay to see (and sit through) Buress, a hot queer comedian like Tig Notaro and Cross? No way.

Cassie: OK, let’s talk about how we’re getting this glimpse into Snelson’s sometimes puerile, sometimes defiant life — Harper’s art and (most affectingly for me) Lee Loughridge’s colours. There’s such a skill to making a reader feel vaguely uncomfortable even looking at a character, and do they ever nail it. What’s grabbing your eye?

Will: I feel like we get right up to the line of caricature in Snelson’s physical features (what’s that little leaflet of hair? A comb … forward?) without crossing it, and that’s a hard thing to nail. The team seems to play it straight with everyone else, which only makes ol’ Melville stick out more as a loser. In other looks, Donna performing in evening gloves was certainly a choice.

Cassie: It really is the colours for me, I think, because I don’t always love being so close to that line you mentioned (and I really don’t love the way the sex scene in the issue is drawn, and how it depicts the woman with Snelson), but those dark washes of colour that break into something harsher, or introduce tiny pockets of warmth, help give the story depth. It also helped to keep me in the space I think we’re supposed to be in, which is being super wary about Melville.

Really, It’s Not a Thing

Will: So I have to ask this to get some international perspective. Is “cancel culture” a talking point in Aussieland? Because it’s really stupid and deployed in bad faith here. Like I tell my media law students, it’s not a new thing — we’ve always had consequences for speech. And the only thing the First Amendment provides is that those consequences can’t come from the government. (Unless they can. But that’s an entirely different discussion.) So when Snelson complains about facing consequences for pulling a Seinfeld, that’s simply the way the world has always worked — although white men certainly have been able to get away with those sorts of things more often.

Cassie: Our defamation laws are stricter than yours, so cancellations really never really seem to stick over here; plenty of men in the public eye who have been revealed to be abusive or racist still have extremely influential jobs and wield their own platforms. (Fun fact: Australia doesn’t have an equivalent to the First Amendment; we have no statutory declaration for freedom of expression.) As for the act of more people organising for change and amplifying concerns online, which gets called “cancel culture”? That absolutely happens, but a) Yes, good, we need to fix a lot of stuff, and b) Exactly what you’ve said — the ideas aren’t new. They’re just more easily heard.

More directly: Do we have our Snelsons? We sure do. Do they also believe the “cancel culture” monster is coming for them? You bet. Does that make reading this comic a strange, provoking, discomfiting experience? Absolutely.

Slight Gags

- Three great short prose stories in the usual AHOY bonus bits: Dave Giarrusso’s “Piano, Man” builds to a fine punchline; Kate Liggera’s “Short-Term Memory” hits a poignant spot and Bryce Ingman’s “BJ and the Sun Bear” is a fun romp about a man and a truck-driving bear who like to bite butts.

- Do we need more truck-driving bears? Probably.

- Not sure about the butt biting, though.

- Way to get some, Donna.

- That was unfair to Marcy Playground. [Grote’s note: Nah, it wasn’t.]

- Custom and tradition — heckuva way to protect expression there, Other Former English Colony and Mother England Herself.

- The checkered Vans Melville wears on stage both capture how trapped he is in the past and bring back a flood of memories. How dare you, sir.

- Cows deserve more respect than they get in this issue.