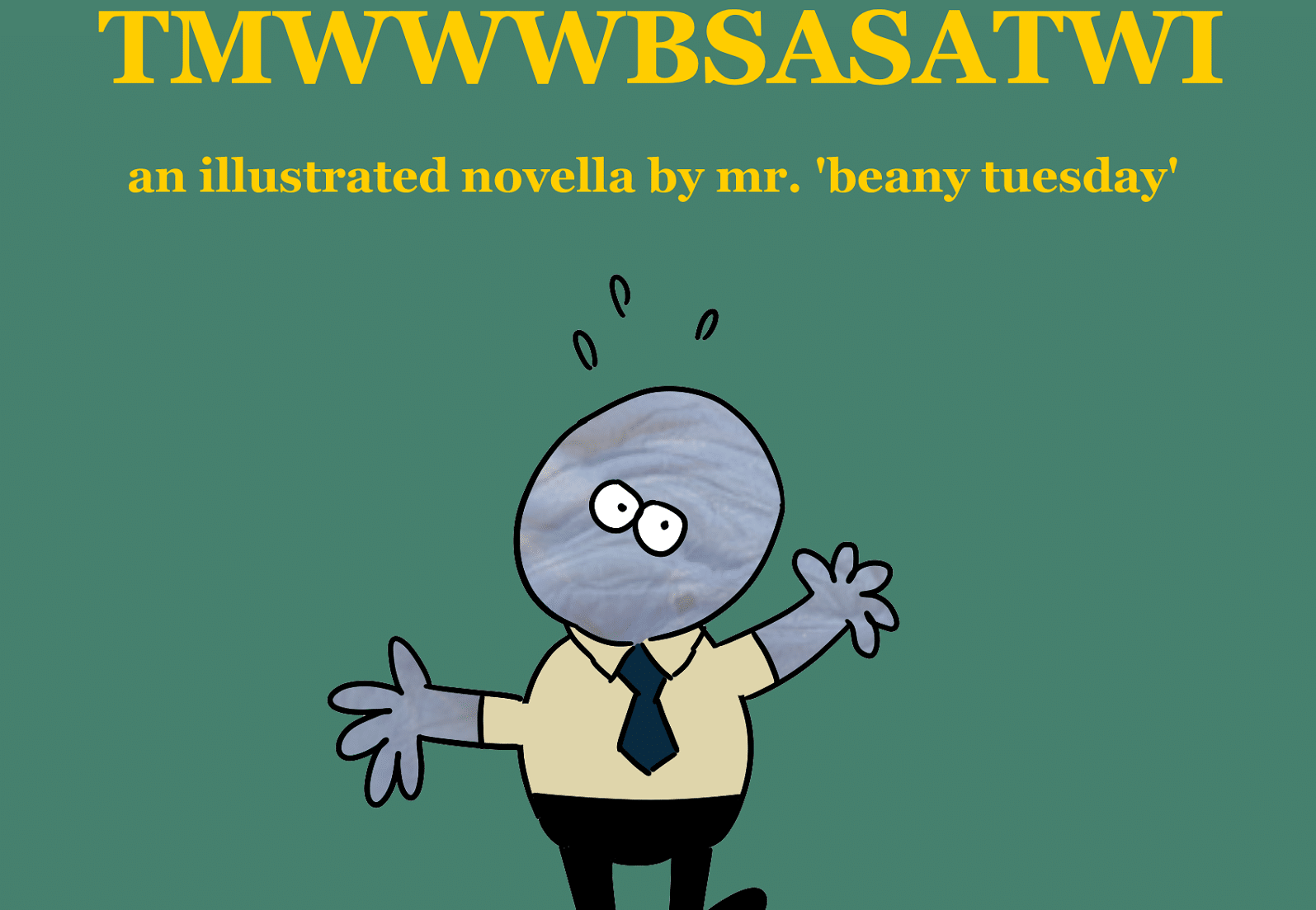

Popular across Instagram and Twitter, you may have already seen Beany Tuesday’s work without realizing it. If you’ve ever seen a meme asking “Why am I laughing?” you’ve stumbled into a Beany Tuesday classic. Known mainly as a leftist cartoonist, Beany Tuesday’s popularity stems from the way he captures the experience of being on the internet, or going to the store, or the continued existence of Harry Potter. In recent years, Beany Tuesday has expanded into longer narratives, including a manga-inspired serialized comic, Bad Enders, and a number of novellas, the most recent of which is titled TMWWWBSASATWI. This interview with Beany Tuesday talks about their transitions to long-form and print, as well as decision-making within the comics medium.

Comic Strips

Ian Gregory: Your first print comic came out last year. Did you have to make any adjustments for a comic meant to be viewed on paper, instead of on a screen?

Beany Tuesday: The main difference was that I had a lot more space to work with. I got my start posting comics on Instagram, so I got used to making my pages all square. Plus, posting anything online you have to be kind of aware of like, will this read clearly on someone’s phone? Will it catch their attention? If someone is mindlessly scrolling through Twitter, they’re way less likely to bother reading a comic which has like 8 different panels, each with their own speech bubbles, all crammed onto one page on a 6-inch screen, versus one which has like one “panel” per page, and is organized for easy readability. But if they’ve already made the commitment to read something, print or not, then you can, you know, actually lay the page out like a human being, instead of like some sort of debased engagement-chasing morlock. Which is a nice change of pace.

Gregory: A lot of your most popular comics are political – some of your recurring themes include “how the right uses the internet” and “the impending ecological catastrophe.” What’s your relationship to your political audience – and your status as a “leftist cartoonist?”

Tuesday: I think I try to be a little less heavy-handed about it than I used to— which definitely isn’t to say that I’m trying to hide my beliefs, or make my comics more apolitical for mass appeal or something. But there are so many cartoonists out there, and even comedians more broadly, where their whole “joke” is just them saying something the audience already agrees with or knows to be obviously true. I’m not one of those comedians who styles themselves as some kind of “brave truth-teller” or whatever, nor do I think I’m any smarter than my audience. So I have no business trying to lecture them about anything. What I CAN do is take those shared truths and experiences, those political axioms, and use them as a jumping off point. Like, oh, the republicans and democrats are both bad? Wow, shocker. I’m going to give my audience the respect of assuming they already know that fact intimately, by virtue of being alive and having a brain. Rather than just parrot that notion back to them, I’m going to expand it into something weird or absurd, use it as a setup rather than a punchline. I think jokes like that do the audience the service of empathizing with their personal experiences, without coming off like a huge circle jerk. And I say that in the least glamorous, least heroically back-patting way possible. As for the online right wingers, the jokes pretty much write themselves— there’s something about the combination of reactionary politics and insular internet brain-fry that just creates some real bizarre specimens, like characters in a sci-fi movie who’ve had their DNA spliced too much. People who are vehemently homophobic, but who also believe that eating their own cum will grant them superhuman abilities— that type of thing.

Gregory: Some of your recurring topics include animals and religion – especially in your “Two Friends Talk” series. How much would you say your background in zoology and philosophy informs your subject material?

Tuesday: I have a passing interest in animals, I think they’re really neat. That’s more or less the extent of that. As for philosophy, I think it pretty much involves itself into every part of your life, as cliche as it sounds. I don’t read a lot of proper philosophy anymore, but I definitely think studying it heavily in college rewired my brain for the better, and I think you can glimpse that in a lot of my work.

Gregory: I’m a big fan of your character design comics – fictional presidential candidates, TV show characters, or “types of guys.” How do you approach this kind of comic, and what kind of relationship does it have to the character designs in your narrative works?

Tuesday: Character design is probably my number two creative passion, after comedy. Brevity is the soul of wit, as they say, and so in my one-off comics I typically try to have the characters be immediately identifiable by their appearance (this guy’s a scumbag, this guy’s a nerd, etc). And in cases where the character’s appearance itself is part of the humor, they should also be kind of weird and novel in an interesting or memorable way, too. I think training myself to create these types of bold characters has helped improve my character design sensibilities overall. I know I’ve made a really good design when I can just look at it, and based on appearance alone my brain will start effortlessly spitting out the character’s personality traits, backstory, and comedic details. My best comics are written this way, too— if the core idea is strong enough, the details just spill out.

Bad Enders

Gregory: How do you balance long-form works like Bad Enders and TMWWWBSASATWI with the immediate popularity of your short strips?

Tuesday: There’s no balance, I basically just suffer. When I get an idea for something long form that I think is really solid, the idea will usually possess my mind so strongly that I basically just have to stop what I’m doing and make it. Which makes me anxious because I know that my short form stuff is not only the moneymaker, but what the vast majority of people come to me for. I feel like one of those popular indie rockers who decides that his next album is going to be a foray into like, ambient music or something. And of course the audience is like “Dude, what are you doing? Just stick to what you were doing before— you were good at it, and we liked it, it was a perfect arrangement.” I can empathize, I’ve been in that audience before, we all have. But if you’re that artist, you gotta follow where your inspiration is at the moment, gotta grow creatively in a direction that feels good to you, even if everyone else hates it. I mean, what else can you do? Anyway, I basically just dwell on that and feel like crap.

Gregory: Bad Enders is a “manga style” Western comic – and in the first issue you express a lot of concern about what that means. What were the manga elements you tried to incorporate into the story, and what were you trying to avoid?

Tuesday: Manga has been a part of my life literally as long as I can remember. I was born in Indonesia, and moved to the U.S when I was very young. My parents had a big collection of manga, Dragon Ball and Doraemon and Astro Boy, that my mom would translate to me in english. I’ve been reading it ever since. I don’t read superhero comics. I don’t read all that many indie comics, either. Manga are the reason I love comic books, plain and simple. The aesthetics of manga— art, story, worldbuilding— have had a massive influence on me. How could they not? That stuff rules! And I didn’t want to shy away from that influence just because I’m some white American dude.

Remember in the mid 2000s? When manga was just becoming popular, and every American comic franchise was hopping on board to do like, the Sabrina the Teenage Witch ‘manga’, the X-Men ‘manga’, the Funky Winkerbean ‘manga’?

That’s what I was trying to avoid.

Gregory: Bad Enders takes place in a battle shonen setting, but stars characters who would normally exist in the background. What kind of planning did you put into the setting and how characters would interact with it?

Tuesday: Shonen, as a genre, is about youth. It’s about being an age where your future feels limitless. The stories are marketed to young people, sure, but are also usually about young people, who go on grand, fantastical adventures, and most importantly, grow. Superhero comics are similar in a lot of ways; they’re stories aimed at young men, about ordinary people who have greatness thrust upon them, which feature simplistic good vs evil narratives. But superhero comics are usually rooted in sameness, status quo. A hero has a moment of growth, receives his powers, and then stays more or less the same as he fights to keep the world more or less the same, with major shakeups almost always being brief and temporary. In most Shonen series, the characters will never stop growing, getting stronger, venturing further and further out into the unknown, facing greater and greater challenges as they do so. Everything is new, the world is limitless, and your journey never has to end. In an idealized sense, this is what it means to be young. And so when you’re young, these sorts of stories are nothing short of magical.

Then you get to adulthood, and everything is just… stagnant.

When I got older, the types of manga that began to appeal to me more were ones like Kaiji, Real, or Saikyo Densetsu Kurosawa. In these stories the ultimate antagonistic force was no longer some fantastical villain, or a terrifying monster, or an apocalyptic prophecy which could only be thwarted by one special little boy— it was life. The harsh mundanity of being someone of no great significance, struggling to scrape meaning out of an existence that has utterly flatlined. Disappointment, mediocrity, a world which is, in fact, limited in every conceivable way. This is what it means to be an adult.

Bad Enders is about a young person who becomes an adult.

Gregory: What would you say is the most valuable thing you learned while working on Bad Enders?

Tuesday: That making a non-serialized comic this long was an insane choice

Novella

Gregory: TMWWWBSASATWI is the third story you’ve put out, and the longest. What made you want to start working in prose?

Tuesday: (Fourth, if you count Guide To Fashion.)

A lot of my comics are super wordy, and I think the more I made them the more I realized how much I loved writing. I think really good descriptive prose can be funnier, more visceral, and more poignant than even the greatest of illustrations; it has a storytelling power which simply can’t be replicated by other mediums. Once I got a taste of that power, I just couldn’t help myself.

Gregory: A lot of your works start with a disclaimer that they’re “outsider art” – what draws you to that label?

Tuesday: It’s completely just a joke. As a kid, I remember going into an art museum and seeing my parents gazing ponderously into this awful, completely amateurish painting. And when I asked why it was in here, my mom told me it was “outsider art”— it was painted by like, some dude in a barn or something. And it’s like— okay? It still sucks. If we get to be graded on an arbitrary curve here, I want in.

A lot of outsider art is great, of course, but the value isn’t intrinsic to the title.

Gregory: Both Bad Enders and TMWWWBSASATWI take place in the office, and deal with the mundanity and bizarreness of the workplace. What is compelling to you about the office as a setting?

Tuesday: I think the professional setting of the office is kind of an emblem of human misery; specifically, the misery of having to exist in modern society. You could say capitalist, but I think it goes even deeper than that; can we realistically imagine a socialist society existing without any sort of white-collar drudgery? In any case, at an office job you’re so divorced from everything you’re actually doing in the world that it’s kind of surreal; it’s like existing in another dimension entirely. However, there’s also a glimmer of hope; the camaraderie of your coworkers, who are made to exist in the same hell that you are, and who you therefore can— despite how totally weird or unlikable they might otherwise be— empathize with. The office is almost more like a symbol than a setting to me; a microcosm of our modern life. So it’s perfect for the kind of stories about ‘adulthood’ that I described above.

Gregory: What was your planning process for integrating illustrations into TMWWWBSASATWI?

Tuesday: Comedy is about delivering certain pieces of information in a specific order, with a specific timing. For the order and timing of certain jokes to work optimally, sometimes it was necessary to present that information visually. (As mentioned before, writing has certain descriptive powers that visual art doesn’t, and of course the opposite is also true.)

When a joke I envisioned required a visual component, I gave it one. Simple as that. Some things must be seen, not read.

Gregory: With TMWWWBSASATWI out, and Bad Enders completed, what are you planning next?

Tuesday: I’d like to continue making a character-based series, alongside my one-off comics. Learning from the mistakes I made in Bad Enders, I want to sit down and figure out something that will play to my strengths. And dear God, it will be serialized page by page this time.

Ian Gregory is a writer and co-host of giant robots podcast Mech Ado About Nothing.