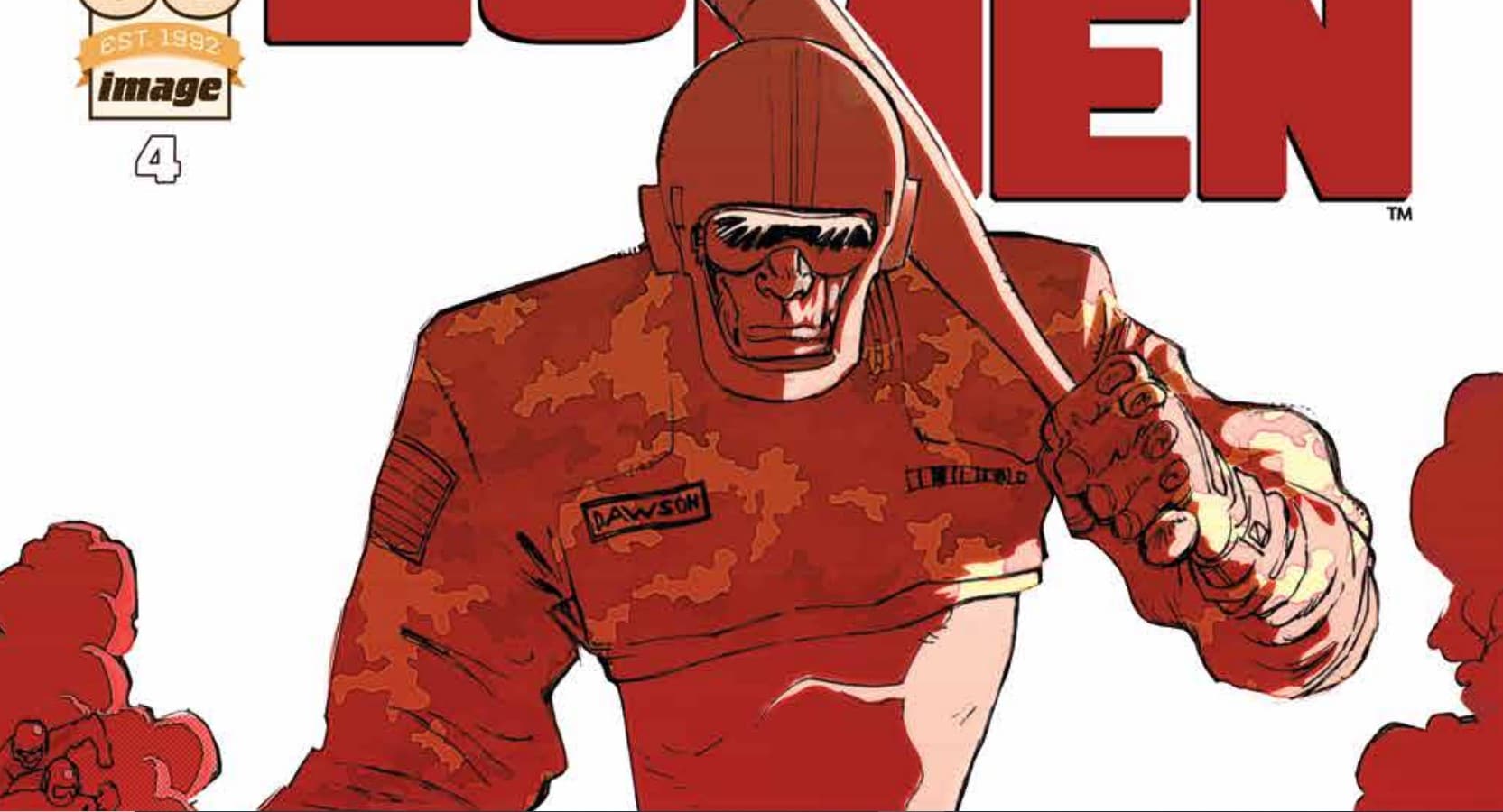

The Battle of Beaux Arts has begun. The American super-force the Suicide Cowboys launches an all-out assault on the Iron Star, hoping to decapitate the Soviet forces in one decisive action. Meanwhile, back in the states, we learn about President Goode’s plans for the monster known as 6Bill. It’s all in Image’s 20th Century Men #4, written by Deniz Camp, drawn by S. Morian and lettered by Aditya Bidikar.

“The mere fact of the abandonment of regular warfare proves the disappearance of the national before the local centers of Government. When the disasters of the standing army became regular, the rising of the guerrillas became general, and the body of the people, hardly thinking of the national defeats, exulted in the local successes of their heroes.”

— Karl Marx, 1854

Sean: I want to begin by asking you a question: Have you read Kyle Baker’s Nat Turner?

Ritesh: I have, yes!

Sean: OK, good. I’m thinking about the book in part due to the nature of the narration in this issue. (That, and the scenes with President Goode are extremely Baker-esque.) For those of you who haven’t read Nat Turner, it uses found documentation to tell the story of the titular historical figure, a slave who led a revolt that failed. More specifically, it used the narration as a kind of contrast between the visuals. How the historical record wasn’t necessarily one to be trusted and that the act of reading isn’t simply passively engaging with a text, but rather reading between the lines.

I feel like the fourth issue of 20th Century Men is doing something similar with its use of historical documentation.

Ritesh: It’s important that we note its usage of constructed historical documentation. The work is very clearly and evidently rooted in real history, research and study of imperialism, but the way it is deployed in this alternate-history genre story featuring super-soldiers? It’s using reality as a resource to inform and to augment a fictional context that once again loops right back to speaking to reality, just through that powerful genre lens and language.

Alan Moore and Warren Ellis’ works in this genre terrain were very much obsessed with alternate histories of the 20th century — Watchmen and Wildstorm. The geo-political impact and outcome of what would happen if such horrifically powerful people did exist. It’s very much rooted in and an outgrowth of the British Angry Comics that Pat Mills was the godfather of, that 2000AD became the bedrock for with its various Future Shocks and strips, wherein Moore honed his skill and Ellis’ sensibilities were forged. This feels like it’s an evolution of that. It goes far beyond that and the constraints of those texts and their “superhero” constructions and genre-response nature to be something else.

This is not a “superhero” book.

This has no interest in being one.

And if those two’s works, as well as the rest of the British Invasion movement, were very much America and Britain/Europe centric, this gets beyond that narrow framing. Watchmen was only ever the American perspective. The Russians are equally as vital as players, and the work is much, much more smart about condemning both the Americans (and the British, who are crucial pieces of shit) and the Russians.

This to me is an evolution of that school of comics that no icon of that school of comics could write. This is something only Deniz Camp could write. He has a perspective they did not. He’s not a white guy in Northampton or London raised adjacent to Christianity. He’s a creator of MENA and Asian descent raised Muslim, and a guy who’s lived in Istanbul for a good while doing vital work. He’s seen and experienced some shit those dudes have not. There is an informed rage here, for me.

Sean: Perhaps most telling is who’s included in the documentation. Since you brought in the superhero element and Alan Moore specifically, let’s talk about Watchmen. As many who have read the book will tell you, Watchmen includes 11 prose sections at the end of each of its chapters. They document various elements of the superhero throughout history, including interviews, scrapbooks, therapist notes and other such things.

Likewise, 20th Century Men’s documentation includes interviews with generals, scientists and other propagandistic pieces. But it also includes a perspective that, much like the visual element of Nat Turner, counteracts the story being presented to us. We are seeing the events from the perspective of the soldiers on the ground, the people in the halls of power. We are receiving their perspectives visually.

But we’re also seeing things from the perspective of one of the people being “liberated” by the Russians and Americans: Farzana Joya. Joya’s perspective, more than anyone else’s, is key to understanding the story being told. Moreover, it is one that is conspicuously missing from the various tales of alternate histories told by the likes of Moore and Ellis. Not that of those with power, those who can change the world for their own prerogative. But rather, the perspective of someone powerless to stop any of this. The child of a nation being overturn by bombs and superheroic football players and mech-suited scientists. It’s not framed as the absurdity of Marshall Law or the perverse glee of The Authority. It’s just horrific.

Ritesh: There’s no straight up ill-considered Fu Manchu-recreation like in The Authority or League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, no. There is a lot of deliberate racism in the book, reflecting the nature of these monstrous characters, but you can tell it’s not done as indulgence of any sort. The framing has been considered a lot more. The Orientalism of these bastards, that’s what Joya’s perspective is there to dismantle. Her words cut so clearly through all the bullshit of these dudes. They’re all just talking about themselves. It’s all me, me, me, us, us, us. There is never a word said about the people of Afghanistan they’re inflicting all this horror upon.

And it’s because they’re The Other. They’re The Orient. They are Lesser People. In fact, they’re not “people” at all. The Russians and the Americans, they’re people. The Afghans? Not so much. They don’t care about them, not beyond them and their own purposes and needs. They don’t view them as human. They view them as a resource, a prize, an object, something to use or gain something from.

It’s all about them — the Russians and the Americans, the only true people and humans in all this, in their eyes — though it might be too crass to say. It’s why it’s easier to center them and their humanity, while making the Afghans an abstract negative space in their tellings.

Sean: Even the more critical appraisal of the war from Artyom “Krylov” Borovik emphasizes the death of the Russian soldiers over the devastation they are enacting upon a land that isn’t theirs in the first place. There’s no engagement with the wider culture they’re fighting a proxy war in. They’re just using it as a backdrop for their own bullshit.

Perhaps due to how recently I’ve seen it, I can’t help but think of James Gray’s Armageddon Time. (Gray also directed The Lost City of Z.) The film is one in a recent trend of filmmakers making movies about their childhood (including, but not limited to, Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood, The Fablemans and Belfast), and this one is very much the one made by someone often compared to Christopher Nolan. More specifically, it’s about a middle-class Jewish kid — Paul Graff — from New York who has to move from the public school environment to the private school one.

Among the reasons for Paul moving to a private school is his friendship with a Black kid, Johnny Davis. Johnny is a homeless kid who constantly gets into trouble with his teachers. The ending of the film involves Paul convincing Johnny to help him steal a computer. The two get arrested and Paul gets off scott free while Johnny goes to jail.

The problem here is how the film treats Johnny as an object lesson for Paul to learn about his own complicity in a racist system. Johnny’s life is sacrificed (in that he literally does what so many Black characters do in movies like this and takes the fall for the lighter-skinned hero) so Paul can learn something. We don’t get much of an interiority of Johnny’s life, and what we do get feels like a white person’s assumption of it. There’s no engagement with the life beyond the misery and the few popular strands of non-white culture that eked out into the “mainstream.” He does drugs, he listens to hip-hop, he’s poor and on the run. Other Black men who appear in the film (all two of them) are framed as threatening and hostile to both children. (Perhaps most tellingly, Johnny introduces himself to Paul by deriding disco as being an uncool white guy thing.)

To the western mind, the people not of the west matter. They are important. They are valuable. But they are important in the way that a work of art or a rare mineral is important. They are objects. And oftentimes, when given the choice between saving an object and a person, my culture emphasizes saving the latter.

Ritesh: Yeah. It’s a bloody, depressive issue of reflection upon the monstrosity of it all. And god … it hits hard. I said it when I first read it, and rereading it over and over, I still think it’s true:

This is one of the best issues of a comic I’ve ever read.

Sean: On a sheer craft level, this is some of the most horrific, brilliant stuff I’ve read all year. The kind of work that gets an entire spotlight dedicated to it. From small stuff like Bidikar’s lettering being different for each of the various writers engaging with the events of the issue to the way Morian draws and colors people dying all the way to Camp’s brilliant narrative and formal conceits.

I mean, this is an issue about the horrors of war where one of the sides is dressed like goddamn football players! There’s a background gag where Elvis’ name is spelled EVILS! “No, Mr. President. He hired us a law firm.” Just so many things this issue does and does amazingly well.

Ritesh: That initial spread of the Suicide Cowboys charing the reader, like, jesus. My god. Morian was tapping into some Kirby and Miller all at once while being totally himself. That image is now seared into my brain.

And yeah, Bidikar somehow takes the herculean task of lettering captions in various fonts that are all distinct but also don’t clash against one another or the page and “fit” … and he does it. It works. The reading takes a second for you to get used to, but once you do, it’s seamless. It all holds and has a special flavor.

To weave all of that together and make a cohesive whole like this? It’s incredible to me. This is what comics is all about for me. Pure, beautiful synthesis.

It’s like magic.

Sean: Also, and this is going to bother me if I don’t say it, Marx never said Man is Fluid. It was Engels.

Ritesh Babu is a comics history nut who spends far too much time writing about weird stuff and cosmic nonsense.