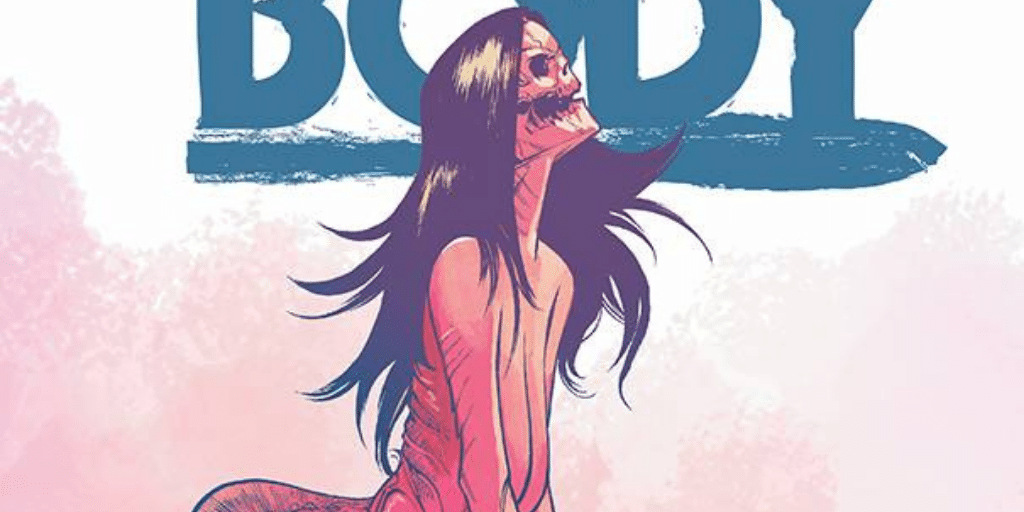

The cult of Mylo grows, but the mystical mushroom secret has roots in the much deeper, darker world of I Breathed a Body #4 by Zac Thompson, Andy MacDonald, Triona Farrell and Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou.

CW: I Breathed a Body #4 features images of suicide and self-harm, and this article will be discussing those images.

Zachary Jenkins: We really, truly thought we knew where this was going. Mushroom-powered internet was actually connected to the fae. OK, I can get behind that. But Rob, my friend, were you ready for the revelations we learned in this issue?

Robert Secundus: I was not. Not at all. We began this series with “isn’t Logan Paul problematic?” Last issue it was “the internet is powered by dark magic.” But now? I’m trying to figure out how I’d describe the series. It’s tempting to say I Breathed A Body is The Social Network meets A Dark Song, but the parasocial fungal fae apocalypse that Thompson, MacDonald, Farrell, and Otsmane-Elhaou have created is so much more. Boy, howdy, is it a lot more.

Neon Suns Above, Dark Bridges Below

RS: I really want to take a moment to just dive into this art, because in this issue it’s like — you know In anime when some Fighty Person has been doing a Big Fight, and they’re already extremely powerful — but then things escalate, and they say something like, “Oh yeah, I’ve been fighting with 700 pound weights holding me down this entire time. It’s TIME TO TAKE THEM OFF.” That’s what this issue feels like for MacDonald, Farrell and Otsmane-Elhaou. As the reality drifts into something that transcends this world, and as holes open up to the reality below this world, they all just go for it.

ZJ: Just, damn son. MacDonald and Farrell just go all out here. It’s beautiful and grotesque and mesmerizing and disturbing and everything you wanted in this book. When the impressionable teens begin injecting themselves with Mylo’s blood and commiting group suicide, it’s haunting. And that’s immediately offset by their awe-inspiring transformation into fungal beasts. I’m not a big gore guy, the Saw franchise is pretty much exactly what I don’t want as entertainment. I quit watching Invincible because it was too much for me. But this? Something about this speaks to me.

Farrell pushes the tone of these scenes. From the sterile, realistic shades at the start of the issue, she transitions into something surreal, impressionistic, other. It’s a tour-de-force for a team that has been stepping up their game in every issue.

RS: The purples, the greens, the reds — it’s all so widely beautiful, and somehow more haunting for that beauty. My first impulse is to compare it to movies like Midsommar that make great horrifying use of light and color, but I think, especially when I look at that second to last page, it reminds me of something older, of old Vertigo horror comics and similar stuff from that era. A lot of that stuff has been lost, because DC absurdly recolors their classics in the blandest ways possible, but if you look at a scan of the original coloring of Swamp Thing, or even something like the original coloring for The Killing Joke, you’ll see what great use colorists got out of things like strange red skies.This is all especially important for this issue, in order to provide stark contrast for the final page’s reveal — what looks to me to be a dark Brooklyn Bridge in some reality beneath the Earth, in a place that seems mostly sapped of color.

I’m reminded of Hart Crane, about that bridge, composed in his mind of “orphic strings, Sidereal phalanxes, [which] leap and converge” (The Bridge 7. 91-92). Consider how he opens his epic poem to that structure that became a symbol for America:

Under thy shadow by the piers I waited;

Only in darkness is thy shadow clear.

The City’s fiery parcels all undone,

Already snow submerges an iron year . . .

O Sleepless as the river under thee,

Vaulting the sea, the prairies’ dreaming sod,

Unto us lowliest sometime sweep, descend

And of the curveship lend a myth to God. (The Bridge 1. 37-44)

Anyway. That’s at least what it looks like to me. It might just be some bridge.

The Internet of Ghosts

ZJ: Reading this, Rob, you DM’d me asking “IS THE MUSHROOM INTERNET MADE IN PART OUT OF GHOSTS?” which, for this book that started with us talking about influencer culture, is a pretty wild turn. Wilder still was the truth that “the magic mushrooms internet is powered by ghosts from mushroom hell.” We talked about swerves last issue, as this went from Cronenburg to Clive Barker, were you expecting it to swerve this hard?

RS: I very much was not. I thought, “Oh, OK, last issue was the Big Swerve, and things will carry on now until we hit the end.” I was not expecting things to escalate further like this. Every technological advancement is a sacrifice; every act of creation here is also some kind of slaughter. It’s a striking reveal, but it doesn’t seem a very hyperbolic depiction of our tech-lords; we know that the vast, vast majority of internet products advertised to us act like we’re users but effectively treat us as the products. A technological advancement built out of souls isn’t that much of an escalation from a technological advancement that relies on our data, that sells our personalities, histories, memories, preferences, choices to the highest bidder that that bidder might better prey on us.

At one point Bramwell quotes scripture when describing the Gelbacut, the ritual enacted here; expanding the quotation, Isaiah 40: 6-8 reads as follows: “All flesh is grass, and all the goodliness thereof is as the flower of the field:/ The grass withereth, the flower fadeth: because the spirit of the Lord bloweth upon it: surely the people is grass./ The grass withereth, the flower fadeth: but the word of our God shall stand for ever.” In the original quotation, flesh, standing in for human lives, is compared to grass as both wither, in contrast to divine things that remain eternal. “All flesh is grass” has come to function as a kind of memento mori, removed from this context; you’ll see it often in older graveyards, and I think the standard meaning has shifted a bit from these origins; it’s a reminder that all flesh will, at some point, be plotted in dirt. All flesh will feed grass and become grass. Bramwell says that “the Gelbacut see all flesh as grass. Lifeforms are processes, not things.” So from our point of view, this ritual (and, again, every technological advancement Bramwell has made) involves slaughter in exchange for something else. But this isn’t at all the case from the Gelbacut’s point of view; things aren’t killed and things aren’t created. A process is just shifted from one mode to another.

ZJ: It’s an appropriately nihilistic take on this. Bramwell doesn’t see himself as evil, he just doesn’t see morality as we do. Now, I’m going to take the bold stance and say we shouldn’t ritually sacrifice ourselves for the betterment of internet mushroom ghosts. This whole thing takes the “it’s just a prank” ethos of some corners of the web to the natural conclusion. It says the harm isn’t relevant because of the intent. It wasn’t serious. No one meant anything by it. In the end no one died. What if you don’t see death, human death, as a negative outcome?

It’s a trick this book, and Thompson’s work on the whole, has pulled frequently. Find something normal, push it one step toward the weird, one step beyond the bounds of human norms. Then take another, another, another. It’s boiling a frog in water. We, and the characters in the narrative, get used to each successive compromise until the process has shifted from one mode to another. This is in the morality, the technology and the actions of Thompson’s stories, and it’s why he is among my favorites working today.

RS: I think there’s also something interesting in equating all the tech advances with the influencer stuff here; both are being controlled by the same guy, and both are relying on the same sacrifices. We oftentimes look at the assholes who abuse a platform as distinct from the platform itself; we see YouTube as some neutral entity, and we see youtubers as people who create helpful or harmful content. But the truth is that the company of YouTube (and each individual human being who runs it) makes the same kind of calculations as its worst users. The Paul Brothers, the Rubins, the Crowders, they all do some harm and receive compensation for it — but by profiting off them, so does YouTube. So does Facebook, and Twitter, and even websites that aren’t marketed as social media platforms, like Medium or Substack.

We normally don’t pay attention to those moral compromises quite as much; they’re too abstract. So I think it’s interesting that the series is structured, as you say, in a boiling-the-frog way, where each issue raises the moral stakes — but it also with each issue gives us more information about the tech company itself here, while it began focused on the far more personal influencer related to that company. It doesn’t just heighten the questions of morality every issue, but more clearly builds to a moral confrontation with that abstract, corporate, tech stuff after grounding it all in a moral confrontation with one specific problematic guy and his harmful content.

Digital Rituals of Self-Harm

RS: This issue gets way more abstract as it outlines the history of a tech company, the functions of its technology, the details of the ritual in play — but it also returns to something personal, as we witness individual members of Milo’s audience tune in, watch the videos, engage in self-harm and become warped by the ritual. And these aren’t all nameless people — Bramwell makes clear a connection between at least a viewer and Anne herself. Last issue I talked about how surprised I was that we haven’t yet had a major incident like this, an influencer attempting to learn from the story of Cobain and other celebrity deaths and lead his followers into self-harm. But this issue, I couldn’t help but see it from the other direction, from the perspective of the audience. And I was reminded that we engage in self-harm in the content we consume all the time. We look for things that will make us angry. We follow evil politicians and empty-headed pundits. We follow subreddits or forums or novelty social media accounts that even curate content designed to frustrate us. And we seek stuff out that will hurt us given our own niches — bad reviews of movies or comics that clearly should have never made it through editorial. Comments on our own articles or videos. We are routinely told “never read the comments” but we always read the comments. And I’ve been using “we” here generally, but uh, this is also a specific “we” because I know the two of us here both do this.

ZJ: I like to tell myself that I’m doing comparative analysis or benchmarking my work against the competition, but really I’m nosey and for some reason continue to search out things that will cause me harm. As a, and I’m about to be insufferable here, niche micro influencer who spent years building himself as a brand, I needed to know if there were conversations going on about me. I got to read incredibly hurtful comments, snide jokes, dehumanizing remarks. And yet? I kept going back, rereading that hate. I customized algorithms and search queries to more efficiently deliver pain. It was deeply unhealthy and a large part of why I wanted to rebrand the website last year; it was tainted as an extension of me.

RS: It’s easy, on the one hand, to separate myself from the kinds of online audience that we see in this issue — I’m very wary of parasocial relationships, and I don’t think that I have any celebrity figure in my life that could lead me to harm — but on the other hand, it’s all too easy to imagine the internet leading myself to engage in a kind of self-harm, because I already engage in a different kind of self-harm on the internet, and I know that this is a common thing. And I think that indicates that the central problem here is bigger than influencers, and it’s bigger than bad platforms and bad algorithms, and it’s bigger even than the internet itself. I think if the internet winked out of existence tomorrow, we’d still be living in a culture where a lot of people seek out stuff that is only going to hurt them, and do so intentionally.

ZJ: Bringing it back to I Breathed A Body directly, what Bramwell does to get Anne to comply is one of the most sickening things I’ve seen as a parent. He directly targets her erstwhile daughter, making sure she is hooked on Mylo, a washed-in-the-blood believer. We’ve talked previously of my fears regarding my children stumbling on harmful content on the internet; the team takes it to the next level here by having Bramwell use his resources to ensure the content gets to his target audience. Anne saying “screw this” and putting the world at risk makes plenty of sense in that context.

RS: The First American tells her, “Your daughter lies beneath the Taustus grooves” — and it’s not clear to me what she means yet. Is her daughter already dead? Did she harm herself like the others? Or does she mean that the way to her daughter is through that underworld? Or something else? I’m excited but also dreading to learn more about that underworld, and about what Anne will find there, in the final issue.

Stray Thoughts

- Even if I still don’t love the highlighter effects, I get what Otsmane-Elhaou was going for, and the team uses it to their advantage here.

- Can’t believe he did this: