Tonight’s Double Feature in Immortal Hulk: Time of Monsters. First— “Time of Monsters”, a tale of the first Hulk, a tragedy of unyielding philosophy written by Al Ewing and Alex Paknadel, art by Juan Ferreyra, and letters by Cory Petit. Second, a trip to the cinema with the sinister Scarecrow in “A Little Fire” written by David Vaughn, and art and letters by Kevin Nowlan.

Chris Eddleman: Wait, I think I got a little lost. Here I was usually editing this column, one of our longest-running, widely beloved, with a cast of talented writers rotating as we swirl the drain towards the inevitable conclusion of Immortal Hulk. But now I find myself drawn to emerald, the shining green door just within reach. I feel its primal call, I need to enter an era of eternal life, some kind of time…immortal.

Zach Rabiroff: Like the gods of Olympus descending from the machine at the end of a Greek drama, our editor from on high hath entered the Times Immortal. And Chris, I couldn’t be more honored and delighted to join you on this special edition of our column, to discuss a prehistoric encounter with a Hulk Before Time. Let’s get this show on the road.

Enkidu’s and Don’ts

ZR: Every Immortal Hulk comic begins with a literary quotation, and since one-shots are allowed no exception, this one starts with a passage from The Epic of Gilgamesh, the Babylonian epic poem that is one of the oldest extant works of literature from anywhere on earth. Actually, Gilgamesh is a collective term used for two different poems, the elder of which was written in the Old Babylonian tongue around 1,000 B.C. – which, as it happens, is substantially later than when this issue takes place in the year 9500. The quote reads as follows:

“I behold thee Enkidu; like a god thou art. Why with the animals wanderest thou on the plain?” – The Epic of Gilgamesh, translated by Stephen Herbert Langdon

So, okay, some context here for folks who were never assigned this banger of a buddy-comedy adventure when they were in middle school. Enkidu is a wild man, created by the gods as a tough, savage nomad, happy to roam with the beasts of the fields and totally ignorant of more civilized ways. Over the course of the poem, he’ll become Gilgamesh’s inseparable buddy, and ultimately the world’s first example of the Best Friend Who Dies to Give Our Hero Important Motivation. But first, he has to be purged of his primitivism (through a close encounter with a friendly sex worker) and brought into the knowledgeable ways of settled society. And while the poem assures us that this is necessary – after all, we wouldn’t have a Gilgamesh/Enkidu team-up without it – it also makes sure we know that it’s not just an unalloyed good. Because to gain knowledge of the settled, agricultural world is also to lose a kind of freedom and innocence that preceded it. It’s the same ambivalent, melancholy bargain that happens in the Garden of Eden story: the understanding that knowledge and self-awareness require us to surrender the purer selves we had before.

And that’s important because while this comic isn’t a buddy adventure and doesn’t involve helpful Babylonian ladies, it is a story about the movement from a nomadic to a settled way of life; about the birth of civilization and authority; and about how those changes never come without a sacrifice. But I’ve gone on more than long enough: Chris, what did you think of the opening of this issue?

CE: So I’ve been rather fascinated (particularly lately, but I wouldn’t say I’m not always thinking about it a little bit) with prehistory. The time before time, the vast majority of humanity’s experiences on our gently rotating verdant marble, as unknown to us as the cosmos at large. Why? It’s nearly impossible to really fully grasp it. To say we can understand prehistory is to say we can understand that which has largely left a bare trace. We aren’t even witnessing the shadows of civilizations long past so much as a charcoal drawing of the shadow, leaving much up to interpretation and little known for certain. It’s a story in pottery and DNA, in mounds and stone. And that’s why it’s incredible. Anyway, I was pretty thrilled to learn we were getting a prehistory story for Immortal Hulk. I think these one-shots have been largely hit or miss, but I’m a pretty large mark for Alex Paknadel and caveman tales so I was ready to roll.

I love that the earliest tale in human history (extant, of course. I think stories were probably invented by humanity roughly the same time there was a fire to sit around and use for the telling) was our quote. That humanity was already talking about the sacrifices necessary for urban civilization is fascinating to me, as Enkidu represents the shift to a more sedentary society from a nomadic one.

Upon doing some prehistory research, I’ve found archaeologists and biologists who puzzle with the shift towards agrarianism. If you think about it, hunter-gathering societies had a much more varied diet, higher protein and caloric density, generally better nutrition. And yet farming allowed for what is the key to large civilizations, it allowed for higher populations. Some researchers consider the dawn of farming to be kind of a great mistake in civilization, giving up a more modest but happier, easier life for large-scale communities. A devil’s bargain, perhaps? I mean, assigning a moral quality to it seems silly, but I wonder if this story is touching on that.

ZR: There is a concept, pioneered by the anthropologist Ronald Wright, called the “progress trap.” The general notion is that societies, in seeking short-term solutions to immediate problems, develop technologies or social systems that cause a domino effect of further and further challenges, until the only outcome is eventual collapse. In this view, the development of agriculture is a classic example of a trap waiting to be sprung. Hunter-gatherer societies, as you point out, have a lot of advantages going for them: varied diets, better nutrition, and far more flexible and easygoing lifestyles (one famous, though highly-debated, 1960’s study found that modern hunter-gatherer societies spent roughly half the time at “work” each week as their industrial counterparts).

So why give it up? Because, according to many ancient historians, they had to. Right around the time this story is set, the earth was undergoing a major period of climate change, and the old modes of finding food were starting to get more difficult. Growing crops began as a kind of backup method for survival, which turned out to be surprisingly productive. The trouble was that the more crops you grow, the more people you need to farm them each year. Which means, in turn, that you need even more crops to feed the new people – not to mention more organized societies to manage all the farming, to say nothing of armies and physical structures to protect the land, which you now can’t even leave lest somebody else take it…and, well, before you know it, you’re stuck in something we call civilization and there’s no way to get out.

And there’s one more thing I want to bring up before we get into the story itself. Farming is unpredictable. It’s dependent on rainfall and temperature in a way that must feel, for lack of any better explanation, like the whim of cruel and arbitrary gods. So alongside the first agricultural societies, archeologists have also found, with chillingly universal regularity, the unmistakable evidence of human sacrifice: food given to the gods for the return of bounty, just like seeds are given to the earth for the next year’s wheat. And it’s on that terrifying note that our story begins.

What Would You Do To Stop Being Puny?

CE: So this tale was solicited as the First Hulk, the original Hulk, as we’ve delved into a little earlier, the Hulk of the distant past. While I kind of have a soft spot for pitches like this, they often seem more subtractive than additive, making the world seem a little bit smaller while making what we formally thought as special to simply be another in a long line. I feel like this iteration was wonderful though. It has familiar motifs but manages to tell its own story. It’s very Hulk-origin, in that a person ends up making a terrible sacrifice. In our modern Hulk’s origin, Bruce Banner sacrifices himself to save the erstwhile Rick Jones, while Tammuz makes an unknowing sacrifice to the goddess of the Green Eye. In our ancient tale, a meteor seems to have fallen to Earth, laced with some ore that radiates gamma energy. The tribe that Tammuz and the elder Adad came from worship a goddess and see this stone as her eye, and Adad is sacrificing Tammuz to appease her. The gamma radiation has destroyed all their crops and animals, and instead of simply leaving, they are stubbornly staying, as Adad thinks this is divine retribution. I enjoyed that motif as well, as Adad is the stubborn, angry elder, much like the present’s Thunderbolt Ross. What’s your read on this, Zach?

ZR: I’m glad you brought up the Thunderbolt Ross parallel with Adad because the two characters are so clearly echoes of one another. If we hadn’t cottoned to it during the opening sequence of the elder man’s deception and murder of poor Tammuz, it’s spelled out for us in capital letters during the later sequence when, while bullying young Shelim into submission and silence, Adad orders him to “Look at me, milksop!”: a distinctly mid-20th century insult that has ever been a favored term of abuse by Banner’s nemesis. The implication here is that, just as Hulks – all Hulks – exist in perpetual cycles of resurrection, so too do the generation of Hulk’s play out the same infernal drama with the same cast of archetypes.

And writers Ewing and Paknadel are cleverly conveying this, in part, through the characters’ names. Adad and Tammuz, as it happens, are both the names of Mesopotamian deities. Adad, specifically was a storm god (Thunderbolt, indeed) and a king, a Fertile Crescent equivalent of Zeus or Jupiter – the very mythological model of the abusive, bullheaded authority figure. As for Tammuz, he was a god of fertility and farming, whose seasonal reappearance in the form of crops was symbolized by a yearly cycle of death, descent into the underworld, and rebirth. I think this is a fantastically interesting notion, that brings the very Marvel Comics concept of a resurrected Hulk into the literal realm of symbolic myth and religion. There’s a liminal sense in which this story we’re reading might not just evoke gods and devils, it might really be a fable about gods and devils. And if that’s true here, so too might it be true in stories about Bruce Banner and his crew of the damned. And that’s before we even get into Juan Ferreyra’s art…

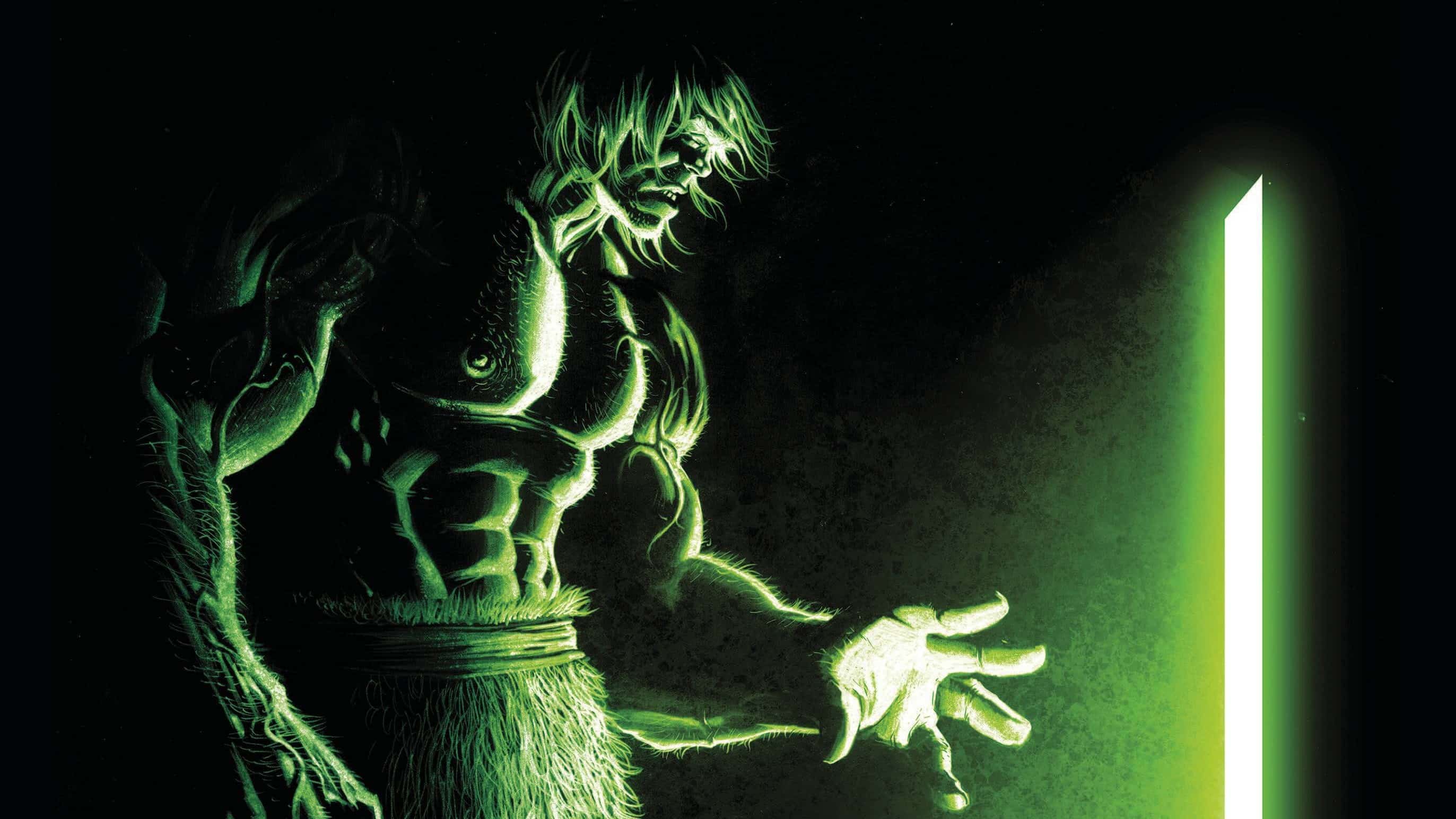

CE: Ferreyra is keeping in line with our Hulk origin motifs by making this comic incredibly horrifying. I think one of the early notes about Immortal Hulk was how it was evoking the original horror genre feel of the early Hulk comics back from the 60s. Ferreyra (who handles all aspects of the art in this issue) brings us that as well, I think noticed earliest in the scene where poor Tammuz is disintegrated by the Green Eye, viscerally being unmade as he wonders why it’s so cold. The portrayal of the people as well, especially Adad, also gives me those EC Comics vibes, with shadowed faces shot from below, as well as lots of shots of grotesque eating, portraying the man as a wanton thoughtless consumer.

And our Tammuz Hulk itself is large and horned, much like early mammals of the Holocene, a megafauna of an already huge creature. What a contrast between his desire to help, even as he’d been turned into something inhuman for the sole purpose of consumption.

ZR: Ferreyra’s work is something unique to Marvel Comics. It’s painterly and evocative in a way that’s reminiscent of the most experimental independent titles, but it retains the kinetic storytelling of traditional superhero books, never becoming muddled in its illustrations or sacrificing clarity for mood and tone. It’s also utterly gorgeous and deliberately hideous in equal measure, and it works alongside Alex Paknadel’s script in a rare sort of chemistry.

Dense prose captions have largely fallen out of fashion in modern comics, and I’ve long felt that this is an unfortunate trend. A great advantage of the comics medium, after all, is its ability to combine the verbal acrobatics of prose novels or poetry with the visual momentum of graphics. And that’s exactly what this issue does, with Paknadel utilizing a third-person narration that nevertheless possesses an intimate knowledge of the thoughts and emotions of the characters it describes. The result is a narrative voice that takes us inside the minds and fears of the cast, even as it maintains a chillingly aloof distance from them. I think it’s a brilliant effect, one that I can’t remember seeing in a Marvel book since at least the days of the Wolfman/Colan/Palmer Tomb of Dracula. I only hope this won’t be the last Ferreyra/Paknadel collaboration because these two are making magic.

CE: The incarnation of the One-Below-All also really stuck with me. While the modern incarnation looks more sharp, like a bird of prey, I thought that this more shapeless primeval avatar fit our material more. It’s a formless green blob, looking as mysterious and primordial as this entire era.

And wow did that final scene get the true horror treatment.

ZR: It’s interesting because it implies that The One Below All, at least in his physical form, is evolving along with everything he touches over time. And evolution is an intriguing motif here, as it has been throughout the main Immortal Hulk series. I’ve mentioned before that the physical shape of the Green Door resembles the monoliths from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, and that comparison becomes even more stark against the semi-civilized background of this story. And just as the monoliths in that film prompted evolutionary leaps along the human family tree, so, too, does The One Below All bring knowledge alongside his twisted curse. As Tammuz slouches toward his village following his resurrection, the narration tells us:

“But his mind is dancing with foxfire. So many ideas. So many ways he can help…the gleaming rock is key. He will crush it. He will smash it. With fire, he will melt the gleam like tallow and shape it cunningly. The fire will make the tools. The tools will make the future.”

It takes us back to the theme we mentioned at the beginning of this piece: the notion that all wisdom brings with it the pain of sacrifice, and that no knowledge comes without its price.

Crowdown

ZR: From the terrifying final splash page of the main story, we move into a backup feature by writer David Vaughan and artist Kevin Nowlan. It’s a little fable, set in the modern day, about third-string Silver Age villain the Scarecrow taking over a movie theater in order to feed off the fears of a kidnapped audience, only to have the tables turned on him when faced by his own fears in the form of Banner’s Hulk. And I have to admit that, after the symphonic performance of the opening story, this little chamber piece left me a tiny bit underwhelmed.

It’s not that it’s bad by any stretch: Vaughan’s script has the neatness of a Stephen King short story, and it’s always a treat to see artwork by the great Kevin Nowlan, whose thick lines and bold colors present a starkly contemporary contrast to the expressionistic visuals of Ferreyra’s work. Maybe my complaint is just the Kuleshov effect at work: my mind couldn’t help but seek connections between this tale and the more substantive story that preceded it, and there frankly aren’t any to be found here. It’s just a little palette cleanser after the main course; some Banner sorbet after the Tammuz mignon. And I suppose there are worse things in the world to get for your extra buck. But what did you think of this second feature, Chris?

CE: I kind of felt similarly. It was certainly an enjoyable read, and still maintained that horror vibe that I’m personally quite fond of in Hulk stories, and I enjoyed the Hulk as sort of a primal punishment for the Scarecrow rather than a simple protagonist. There was one thing I dug into a little bit, which was how Hulk breaks the fourth wall of the movie to kind of break the fourth wall of superhero comics- in that often these bouts of supervillainy seemingly have no motivation other than to simply be mustache-twirly, and that Scarecrow simply doesn’t know what happens when the movie ends because in some ways he isn’t meant to. Kind of an eldritch horror by way of interacting with the meta nature of fiction I suppose. It’s a nice little feature that feels like an EC short by way of superheroes, and that’s at least a lovely finisher to a meaty main course.

Final Thoughts

- If there’s one lesson to be taken away from this comic book, I think it’s this: never, ever eat the glowing green liver.

- Marvel’s Scarecrow is cool and all, but whatever happened to the good old days when he had a gang of trained birds who helped him out when he was too lazy to pick up the phone?