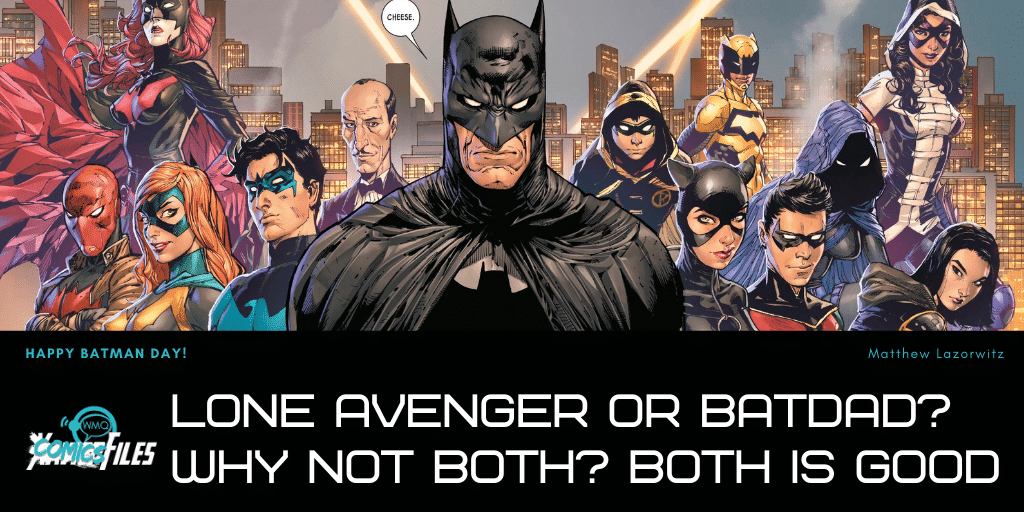

He is the lone avenger of the night. He sits atop gargoyles in Gotham City, eternally alone in his quest for justice. He is Batman.

He is the father figure to a group of young people who fight in his endless war against crime. He works with them to make them better, stronger and frankly better adjusted than he will ever be. He is Batman.

These sound like contradictory visions of a character who has existed for more than 80 years and has had more versions than you can shake a Batarang at. And maybe they are, but just because they are contradictory doesn’t mean they don’t coexist. The Lone Avenger and the BatDad are the extremes of the pendulum from which Batman swings.

I want to start out by dispelling a myth, or at least putting in context a talking point that is often brought up by defenders of The Lone Avenger. Yes, Batman started out, in the first stories by Bill Finger and Bob Kane, as a gun-toting, homicidal, Shadow-esque vigilante. But that was for less than a year. The cover date on “Detective Comics” #27 was May 1939. The cover date for “Detective Comics” #38, the first appearance of Robin, with a smiling Batman on the cover, was April 1940. Citing those early issues as a definitive, not alternative take on Batman is like citing the pilot episode of a TV series as the way the entire series should play out, and I think the track record of changes in TV shows would indicate those changes often work for the best.

Over the course of the ’40s and ’50s, and into the ’60s, Batman’s family would evolve and grow. Robin was consistent, but soon there was Batwoman (Kathy Kane) and Bat-Girl (Bette Kane), Ace the Bathound and Bat-Mite. That is leaving supporting characters like Jim Gordon, who was introduced in the same issue as Batman himself, and Alfred, who would be dead for a period in there (Don’t worry, he got better). Excepting a few love interests, the last major addition to Batman’s supporting cast for most of the next 15 or so years would be Batgirl, Barbara Gordon, in 1967.

Batman operated solo on and off from 1969, when Dick Grayson left for college, until 1983, when Jason Todd was introduced. During that period, Dick would come back, and the “Batman Family” title featured not team-ups with Batman but stories of the characters surrounding him in their own solo adventures.

The death of Jason Todd in 1988’s “A Death in the Family” is the turning point, where Batman’s psychological drive begins to split. Stories like “Man of Steel” #3, the first post-Crisis meeting of Batman and Superman, lay some of this groundwork, establishing that a post-Crisis Batman doesn’t play well with others, and the work of Frank Miller became something of the standard upon which Batman stories were built, meaning you had a Batman who was colder and more remote. I would point out that Miller has a Batman family in “Dark Knight Returns,” but that particular story is a deeper well than I wish to get stuck in here.

But with the response to “A Death in the Family,” the Marv Wolfman-penned Batman/New Titans crossover “A Lonely Place of Dying,” the importance of Robin and the Bat-family was pulled to the fore. The introduction of Tim Drake made it clear that Robin was a balancing force for Batman, the thing that keeps him from going down a dark path. Tim joins Batman, becomes his new surrogate son, and everything is right with the world.

Until it isn’t. Creators seem to have decided that it’s Batman’s drive to stop crime and his drive for perfection that is the thing that keeps him at arm’s length from everyone else. His inability to connect with others is what makes him not go to Dick Grayson after that drive pushes him to the edge and allows Bane to wound him grievously in “Knightfall,” leaving the unstable Azrael in the role of Batman. That drive pushes even Alfred away during “Knightquest: The Search,” where Bruce pushes himself to save his kidnapped doctor and love interest, Shondra Kinsolving.

But, as we will see as we trace this cycle, the response is always the revelation that Batman needs help. In “KnightsEnd,” Nightwing returns, and this is the beginning of Dick Grayson becoming a fixture in the Bat titles again, after being principally a Titans character for about a decade. And when Bruce left Dick in the role of Batman in “Prodigal,” and the two finally hashed out their differences at the end of that story, it put Batman well back on the BatDad path.

Over the next four years, Batman would be the leader of his little family. Robin and Nightwing would be principal supporting characters, and Azrael, Huntress and Oracle would become featured players in events and ongoings. Catwoman, who had been a supporting player and love interest during the latter part of the Jason Todd years, would return as a regular player as well. And with the regular writing trio of Doug Moench, Chuck Dixon and Alan Grant writing the three main Bat books for that time, they maintained a Batman who was, while not the friendliest guy, a capable mentor who cared about his proteges.

The cycle’s next repeat was during the yearlong “No Man’s Land” mega-crossover. After leaving Gotham for three months to center himself, Batman returns and attempts to reclaim the city on his own, with a little help from Oracle and a mysterious new Batgirl, only to fail and lose all his territory to Two-Face. After this defeat, he realizes he needs help and calls his allies back to Gotham, in the process giving the Batgirl identity to Cassandra Cain. Huntress, who had been using the identity, returns to her old one, and by story’s end finally is made a full member of the Bat-family.

The pattern repeats over the next 20 years:

- “Bruce Wayne: Murderer?” and “Bruce Wayne: Fugitive”: Bruce is framed for the murder of radio personality Vesper Fairchild. He drives off his family, only to call them back to aid him in the final confrontation with the person hired to frame him, David Cain.

- “Identity Crisis” and “Infinite Crisis”: When Batman remembers that the Justice League removed his memories of their tampering with the minds of villains, he not only distances himself from his immediate family, but the DC pantheon of heroes in general. It is revealed he built the Brother Eye satellite to spy on heroes, and must face his demons and his actions. This spins into his yearlong walkabout with Dick Grayson and Tim Drake, before returning to Gotham for the Grant Morrison run, where he adds Damian Wayne to his retinue. The more family-oriented Batman continues even after his return from death, with his building of Batman Inc.

- Tom King’s run through “Joker War”: Catching us up to the present, while Batman played the part of the Lone Avenger at the end of Tom King’s 85-issue run, it was revealed that he had a code for punching his allies (?) that allowed him to tell them to trust him. But the death of Alfred again caused him to shut out most of his allies, and only at the end of the current “Joker War” story has he again called them home to aid him.

Those are the biggest cases of Batman pushing and pulling his family away from him and back to him, the major swings of the pendulum. Within the eras between them, the Bat-family would balloon to different sizes. The New 52 era focused mostly on Batman as a solo character, although added Duke Thomas and Harper Row to the family, and had a title focused on Bruce Wayne’s relationship with his son, Damian. For an era with a much darker Batman, he would often show how much he cared about his allies, and while “Death of the Family” showed some fraying around the edges, with the family wondering why Batman didn’t tell them Joker might know his identity, it was not delved into deeply enough to be a major change to the status quo.

I’ve given a lot of information here, without a lot of analysis. I think you need the facts before you can analyze why a character can work on these two very different fronts and still be the same character. And I think that comes down to creators having a different understanding of who Batman is.

There are definitely creators who want the Lone Avenger Batman to be the model, and I think those stories absolutely work in isolation. But creators who work on an extended run of Batman come to realize the borderline psychotic Batman doesn’t work because there’s no dynamism in that character. To use a similar character as an example, the best Punisher stories aren’t stories about the Punisher because he is an unstoppable force who will not stop until he dies. The best Punisher stories are stories about the people around the Punisher and how they react. And so, to keep Batman interesting, creators move him from one extreme to the other to allow for the feeling of movement, even though things always wind up in one of two predetermined places. That’s the trick of corporate superhero storytelling: the illusion of motion.

The thing about the BatDad archetype is you can tell stories with Batman on his own and not have the others around him, and they still work. Lone Avenger-type stories still work when Batman has a supporting cast, as he’s still a brilliant detective and hero, and he has someone other than a remote Alfred to converse with, if that.

But the Lone Avenger has to keep everyone else at such arm’s length that he becomes an agent of the story, a narrative device, more than a character. Which is great for some stories. “Batman: The Animated Series” had episodes like “It’s Never Too Late,” “P.O.V.” and “The Man Who Killed Batman” where he is exactly that, and that makes for a great story. What it doesn’t do is give you a character who is all that interesting on his own.

I also find the BatDad more interesting because it adds a sympathetic side to a character who all too easily exists in a dark place. At his lightest, the modern Batman is the slightly stuffy straight man in a weird world, as in “Batman: The Brave and the Bold.” The most BatDad Batman in modern comics was James Tynion IV’s Batman during his run on “Detective Comics,” where he assembled a whole team of apprentice heroes to train alongside the current Batwoman and Red Robin, and even there, he had a hard time dealing with the emotions brought on by the seeming death of Tim Drake, even though he pushed to keep the team together.

With all his harshness and his sometimes inability to deal with his emotions, one wonders why Batman seeks such a big family. He has more sidekicks and associates than pretty much any other hero. It could be assumed his reasons are selfish. He could be doing it to help maintain his own precarious mental balance, or to build his own army of soldiers to continue his war on crime after he is gone. But I think it’s for something far more altruistic. I’m going to end with a quote from the 20th episode of “Young Justice,” where Wonder Woman confronts Batman about his training of young heroes. I think this quote sums up why heroes need their BatDad.

Wonder Woman: You indoctrinated Robin into crime-fighting at the ripe-old age of 9.

Batman: Robin needed help to bring the man who murdered his family to justice.

Wonder Woman: So he could turn out like you?

Batman: So that he wouldn’t.

In each of his proteges, in some respect or another, Batman sees himself, cold and alone, The Lone Avenger he pictures himself as. And he does everything he can to make sure they wind up as something better. Isn’t that what every father wants for his children, to be in a better place than he was?

Matt Lazorwitz read his first comic at the age of five. It was Who's Who in the DC Universe #2, featuring characters whose names begin with B, which explains so much about his Batman obsession. He writes about comics he loves, and co-hosts the creator interview podcast WMQ&A with Dan Grote.