What if it was actually the year 1724? Wouldn’t that be something? Vishal Gullapalli, Forrest Hollingsworth and Will Nevin team up to talk over Department of Truth #6 by James Tynion IV, Elsa Charretier, Matt Hollingsworth, Aditya Bidikar, Dylan Todd and Steve Foxe.

Will Nevin: Well that was a hell of a final page, wasn’t it?

Vishal Gullapalli: I was unsure how these interlude issues would work, but yeah. I’m already sold on the concept after just one. Fantastic worldbuilding, and a hell of a way to make a statement.

Forrest Hollingsworth: I’m certainly feeling … enlightened.

WN: Let’s cook.

The Bones of It All

WN: Let’s talk about the structure here: five issues of the main storyline followed by the first of two “deviations” with guest artists. Other series have tried this before (Letter 44 comes to mind), but I think — and this is maybe some recency bias at play — this seems to do a better job at both exploring lore and continuing to forward the main story. I also liked the Oswald framing device. Like everything else with this book, I’m eager for what’s next — both in #7 and with the start of the second arc in #8.

VG: You mentioned Letter 44, Will, but my immediate comparison was The Wicked + The Divine, which I thought handled its special issues really well. That being said, I’m immediately more drawn to Department of Truth’s way of handling this, which might just be recency bias. It’s very possible every one of these issues is going to be Oswald’s journey reading through the archives, learning more and more about the sinister truth of the world. And if that’s the case, I don’t think it’s possible for me to complain.

Tynion’s come up with an ingenious way to deliver an infodump to his readers; he’s embedded an actual exposition device into the fabric of his world. What could easily feel like a filler issue or a roadblock instead feels like one of the most substantive issues we’ve gotten to date. I feel like I’m singing way too many praises here, but I legitimately cannot think of any other way to talk about this series.

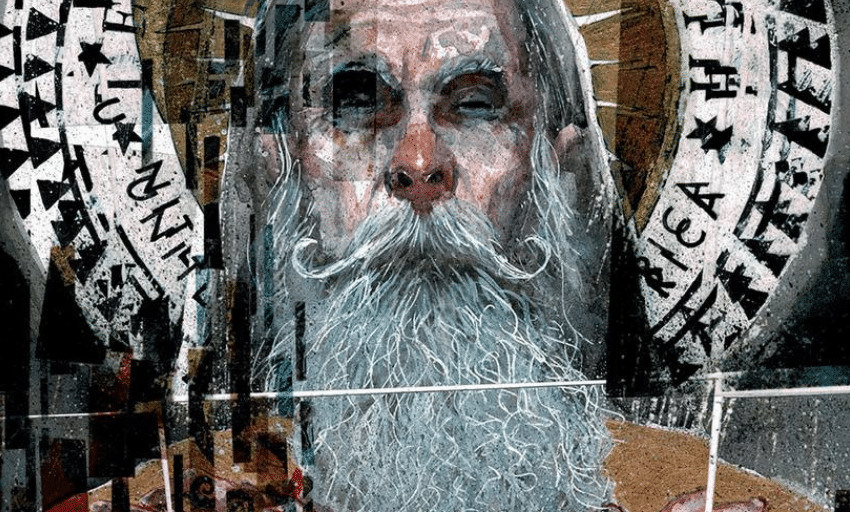

FH: While I imagine the intention is to give Martin Simmonds a (much deserved) break, I also love how well the deviation structure works in tandem with the book’s thematic presentation of perception. We’re following a different protagonist here, and so we literally have different art, a different view. It’s simple but effective and implies a breadth of scope and history that I think complements the narrative exceptionally well.

WN: Not that Simmonds wouldn’t be welcome here, but Charretier’s art nails the medieval storybook feel. This didn’t look or feel at all like a fill-in as this series once again sees your expectations and beats the snot out of them.

The Meat, the Substance of the Thing

WN: The story — a church official is dispatched at the turn of the first millennium to talk to an old woman about some … interesting rumors about her — is surprisingly tense, especially after the characters begin to lay out what they really know. I thought it was really compelling stuff.

VG: Yeah, while the issue’s really just a conversation framed in a sequence of Lee Harvey Oswald reading a book, the conversation itself is so compelling, so constantly adding to the world, that I didn’t even realize there was nothing else happening until I reread the issue. Issues focused around singular conversations are nothing new — Brian Michael Bendis has famously used these to controversial effect — but very rarely does a conversational issue feel compressed. Yet this one does it. I felt like there was as much substance to this issue as there was to the whole first arc of the series.

FH: For my part, I have to say that I found the structure a little too expository. I think some additional art or scenery in the midst of the conversation would’ve helped as a kind of visual aid for the sheer scope of the conspiracy they’re discussing. Especially so, as I’m not as up to date on the particulars of this theory and additional context would’ve helped me keep my bearings (even though I’ll concede that getting lost is both of literal and figurative importance to the book).

WN: The conspiracy theory that underlies this issue — the phantom time hypothesis — is one that’s a little more obscure and proffers that the Catholic Church simply created a few hundred years of history. I wasn’t too familiar with it coming in, but Tynion is so able to argue the fictional case, he almost had me believing it by the time I was finished … which is kinda the point of the book, isn’t it?

VG: I’d heard of the phantom time hypothesis before, and I did like thinking about it as a thought experiment in high school and college, but I’d never really known much more about it than that it was the idea that the church lied about how long the Middle Ages were. I definitely hadn’t realized all that it implied, like Charlemagne’s lack of existence. What I really appreciate here, though, is that this issue blows the concept of the book wide open. No longer is this about fringe conspiracy theorists trying to alter the fabric of reality. The scope isn’t just America post-World War II. We’re looking at a manipulation of the entire world’s history that has already made it into common knowledge and would be impossible to reverse. We’re not trying to prevent the bad guys from winning — we’re living in a world where they already won.

WN: This expansion of sorts is the kind of thing that makes you giddy as you start to think of where this book could be in 10 or 20 issues. There’s really no shortage of conspiracy theories out there, and Tynion has proven he can weave even the most obscure ones into the core narrative he’s telling.

FH: I agree and want to compliment the absolute breadth of what Tynion is doing. Drawing a line from ancient times to present day is a task fraught with contextual hurdles and pitfalls, but I think the team is navigating it as well as can be expected. At times it feels like there’s a burden on the reader to be “in the loop” — obviously risky, and don’t get me started on comics continuity — but it’s an ultimately rewarding one. The idea that a fictional king of nations some thousands of years ago led to Q is as absurd as any on the face, but the pattern recognition element of it, the pervasive nature of passive acceptance … it’s inherently more engaging than trying to keep up on exactly who Xorn is, at least.

Is this how boomers felt about The Da Vinci Code?

The Ugly Spectre of Bigotry

WN: Finally, given the last page reveal, are you worried that the book might be going in a direction where it’s going to be hard to provide the necessary context? Forrest, you pointed out last time that lizard people are a thinly veiled anti-Semitic conspiracy theory. Is it fair to read the Illuminati the same way, or is there a distinction there? It’s certainly not overt bigotry as in when some kook references the Rothschilds or George Soros.

FH: Historically, and even more narrowly within modern conspiracy theory, there isn’t much of a distinction. I don’t think that’s to the book’s detriment, though. As I mentioned above, there’s a significant element of pattern recognition going on here. Tynion wants to forward the idea of a millennia-old cold war for information — to expose the patterns of the thing, the underlying socio-political currents that lead to iterative conspiracy theories, the direct line from Charlemagne to Q and their surprising similarities. To that end, lizard people/reptilians and the Illuminati serve the same purpose — that there’s always a secret group in control. Conspiracy theorists and the people who see their scapegoating for what it is (bigotry) will gravitate to them because they’re big, supposedly tangible things that explain away everything else. One would imagine that kind of monolithic imagery and ideology are of immense value to both the Department of Truth and Black Hat, and so maybe the name or the face changes over time, but the purpose doesn’t.

This is also why I think the upcoming movie adaptation will still be relevant whenever it finally comes out, too. Even if we’ve moved on from Q, anti-vaxxers and the rest by then, how different were they from the Tea Party’s talking points anyways?

VG: So, I wouldn’t dream of claiming that my ignorance prevents harm, but I would like to point out that anecdotally, the Illuminati as a concept were treated in my town growing up as the middle school version of the Boogeyman. We knew the name, we knew the concept, but we all agreed they weren’t real. I always saw “lizard people” as a separate, more harmful concept and belief than the Illuminati. The Illuminati have reached a level of cultural osmosis where it’s far, far more likely that people who’ve heard of them view them as a fairy tale instead of an actual belief.

It’s very possible that I’m wrong, and I really would not like to speak definitively about the harm this could cause as a direction, but I do believe that as long as there is a genuine and legitimate acknowledgement of the roots of the concept of the Illuminati, Tynion will be able to avoid that. I have a lot of faith in the direction this book will take, especially after six issues of a comic that I’ve only ever felt was incredibly thoughtful.

WN: I don’t think my town had any conspiracy theories. How boring.

An Eye for an Eye, A Truth for a Truth

- If millions of Americans believe Oswald is dead … doesn’t that put his actual life immediately in harm’s way?

- The Woman in Red makes another appearance with a neat lettering trick, speaking entirely in archaic banners. It gives her an air of divinity.