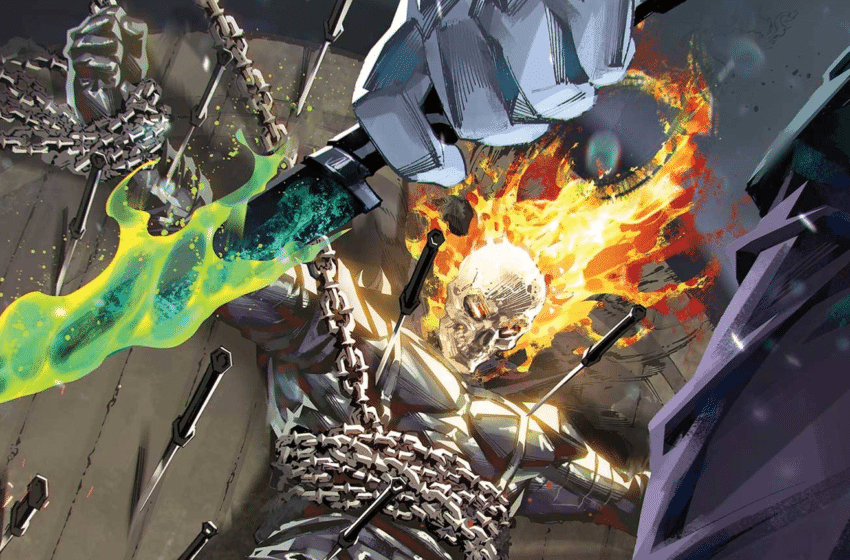

Ghost Rider #1 by Benjamin Percy, Cory Smith, Bryan Valenza, and Travis Lanham

For the double-sized first issue of the new volume of Ghost Rider, I present a reflection in two parts:

Part 1: The Pieces

I want to highlight for you just a few things that happen in this comic:

- A mean goth lady casually tosses a tarantula at a secretary. She works for the FBI.

- A man has had something metaphorically locked up inside of his head, but also literally trapped inside of his head, and so when it begins to break free, his stitched up head-wound opens up as an eye.

- A magician says “here’s my card” and hand’s someone the tarot card The Magician.

- A cenobite pretending to be a therapist breaks character because she just can’t stop talking about how much she loves pain.

- The magician gets the town unraveling by convincing a little demon boy to go beat up another demon boy. We see glimpses of the mounting chaos as one demon runs over a bunch of other demons with a lawnmower. The magician later turns into a big ol’ bird.

- Ghost Rider punches a guy so hard his fist goes right through his chest.

All of that is to say, this comic is a hoot. It’s also grotesque, it’s horrifying— my favorite piece of hell is the painting in the therapist’s office— but above all it’s fun in the way a horror-action comic about a biker with a flaming skull should be.

We don’t have the space to get into the Theory of it all here, but comedy and horror are extremely similar genres with extremely similar foundations and structures. They’re both built on incongruity, and they both rely on timing in their execution. It’s easy to imagine a sloppier version of this comic, where Smith’s art might have been just as striking, just as grotesque, grotesque, and the incidents depicted just as delightfully wild, but without attention to timing, and so the effect would have been lost. Both his layouts and his focus deserve particular praise here. Look to the setup/ punchline of the opening eye; look to the painting sequence, and see how the camera shifts, turns away, turns back, how at times the painting dominates the panel, and other times remains in the background. This comic isn’t just loaded with wonderful moments; they each land because they’re each approached thoughtfully, with precision.

Again, it’s fun. It’s the kind of comic that sticks in your head, where you’ll turn to a friend years down the line and ask, hey, remember that time Johnny Blaze was in Hell, and he stuffed a hellhound’s corpse into a demon grandma’s infernal mailbox?

Part 2: The Picture

My second angle on this comic is, to extend the metaphor, obtuse rather than acute; we’ve talked about individual moments, but now I want to talk about the kind of story we see. The premise: Johnny Blaze is either a superhero trapped in Hell or an ordinary person suffering from episodes of paranoia, hallucinations, derealization, and other signs of psychosis. I’m sorry to turn to the following resource, but it’s the easiest way to get some useful terms here; TVTropes calls this kind of story a Lotus-Eater Machine (if it involves the personal desires of the individual) or, confusingly, a Cuckoo Nest (if it involves mental illness, though the plot doesn’t actually apply to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest), and Ghost Rider #1 plays with both.

It’s such a common plot in serialized genre fiction that you’ve almost certainly encountered it before; the most well known, I think, is Buffy the Vampire Slayer episode 617, “Normal Again,” whose ending is sufficiently ambiguous that one can choose to interpret the entirety of the Buffyverse as the fiction of a severely mentally ill teenager who wishes she was a superhero. In comics, the plot pops up (of course) in Moon Knight, but also in JLA, Doom Patrol, Final Crisis, The Invisibles, The Filth (Morrison is clearly a big fan), Miracleman, For the Man Who Has Everything (Moore also being a fan, I guess), Tom Strong (in an issue by Brubaker, not Moore!), etc etc. In some ways the trope is the reverse of what TVTropes calls the “Broken Masquerade,” which we see in The Matrix or, more appropriately for this story, Jacob’s Ladder. In a “Broken Masquerade,” a character confronts the possibility that their mundane life is false, which in turn shifts the story into another genre. Neo and the audience have to grapple with the possibility that he’s not really an office worker; in a “Normal Again” episode, a character confronts the possibility that their unusual life is false, which dangles the possibility of the narrative shifting from science-fiction, fantasy, superheroes, action, etc into psychological horror or even more simply psychological drama.

I’m telling you all this because even though I love The Matrix and Jacob’s Ladder (and Dark City), I absolutely despise “Normal Again.” And I tend to despise the “Normal Again” plot in serials generally, not for any CinemaSinsy “Tropes= Bad,” reason, but on more specific aesthetic and narrative grounds. In Jacob’s Ladder, the tension for the audience is between whether the main character has some pretty bad PTSD or whether he is literally dead and in Hell. It could go either way, and as the mystery unfolds, the movie at times not only makes the case for either solution, but also makes either solution seem compelling.

Now, consider tuning in in the middle of the sixth season of Buffy. It’s 1997, your favorite tv show is Angel, you love walking by the still-standing Twin Towers, playing Goldeneye with your friends, and logging into America Online’s Instant Messenger. You’ve got a “Joss Whedon is My Master” t-shirt that you will absolutely, unfortunately remember in 2022. But anyway you tune into Buffy and this episode presents you with this tension: Buffy Summers might not be a superhero after all. Buffy Summers might be hallucinating all of this in a psych ward. How will the episode resolve??

In a movie, “it was all A HALLUCINATION” can be an interesting twist that complicates the narrative. In a superhero serial, however, it’s not easily possible for this twist to be compelling; if there is such a twist, the audience learns that the reality of the comic is, in fact, the more boring one, not the exciting escapist genre that led them to pick up the book. “Perhaps this ongoing story is actually mundane” is rarely an exciting tease. Buffy, in 1997, is also not only a superhero serial, but a tv show in the middle of a season. The episode not only asks you to consider the possibility that the exciting things you like might, in fact, actually be boring things, but also that the show might not continue on, when you know it will. I know that Marvel Comics is going to continue publishing Ghost Rider comics, and I know that I would not be interested in reading the ongoing adventures of Johnny Blaze, Guy Who Works On Cars with His Buddy and with His Therapist Works on…. HIMSELF.

And if I’m being honest, I despise a lot of these stories on personal grounds, because my brain is not great at warding off episodes of derealization; I find Jacob’s Ladder at times troubling and at times cathartic, but there’s not much for me to latch onto in “Normal Again.” It toys with mental illness in order to, by means of an ambiguous ending, make the episode seem smart or deep, but all it really manages to do is remind the viewer of the better things it’s imitating. That’s not worth the kind of day I’ll have after watching.

And yet, Ghost Rider #1 works.

In part it works because of the ending; John Blaze’s narration indicates that he still doesn’t fully have a complete handle on what’s real and what’s not. This is something he has to work through. I’d probably have a fonder memory of “Normal Again” if the show had gone on to treat a psychotic break with the gravity it did near death experiences, the death of parents, or even bad breakups; things that weren’t just premises for an episode, but traumas that characters grappled with over time. Make the “Lotus-Eater Machine” plot the impetus for a character arc rather than a one-off gimmick, and it’s far easier to justify its use.

More importantly, the comic rejects ambiguity fairly early on; we know that Johnny Blaze can’t actually be just some normal guy, but so does the magician. By introducing a character who is neither a participant in the masquerade nor the object of the deception, by introducing a point of view not restricted to Blaze’s subjectivity, the comic ensures that there no tension is attempted between what is real and what isn’t, nor between whether or not Blaze will break free. Instead, the issue builds anticipation for the moment he breaks free. Rather than try to interest the viewer in the possibility of Johnny Blaze: Sad Dad, it stokes desire for the moment when the facade will be brought crumbling down.

Miscellaneous Thoughts

- The Magician is the kind of character a kid would create after reading a couple hundred old Vertigo comics in a weekend, and I mean that as a compliment

- It’s really disappointing that it seems all the pre-COVID political-drama-in-hell Ghost Rider stuff is going to remain shelved. This comic is going to be fun, but I’m going to wonder about what other fun might have been had

Robert Secundus is an amateur-angelologist-for-hire.