SPOILER WARNING: The following article contains major spoilers for Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse and Amazing Spider-Man #26.

On May 31, Marvel released Amazing Spider-Man #26, controversially killing Marvel’s most prominent South Asian character, Kamala Khan. She becomes one more of a long line of characters whose deaths happen to fuel Peter Parker’s ever-flowing fountain of guilt. In fact, the issue is a bizarre celebration of the anniversary of the death of Gwen Stacy — a pattern repeated right down to the cover, with its “one of these people will DIE” theme.

The next day, June 1, Marvel, via Sony Pictures Animation, released Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, in which Miles Morales saves a South Asian character who would have otherwise also become nothing more than a tragedy meant to fuel another Spider-Man’s ever-flowing sense of guilt.

There are many themes present in Across the Spider-Verse, but the main conflict in the movie is this: Miles fights, with everything he has, against the belief that a Spider-Man story must include tragic deaths whose only purpose is to heroically inspire the protagonist. Miles fights for a better Spider-Man story.

On multiple fronts, Amazing Spider-Man #26 is a disappointment. Tony Thornley and I have gone into length about that, and we’re not the only ones. The thing that’s perhaps the most exhausting about it, however, is seeing a longtime comics writer dip into the same old, tired tropes like fridging. Some inherent belief, and failure of imagination, led current Amazing Spider-Man writer Zeb Wells to veer away from new stories, and instead just spin out tired repeats of the old ones. June 1, 2023, is also the 50-year anniversary of The Amazing Spider-Man #121 — “The Night Gwen Stacy Died.” Kamala Khan died as part of a celebration of that anniversary.

Both the deaths of Gwen Stacy and Kamala Khan came about from writers who believed that personal tragedy is an essential part of not just Spider-Man’s origin, but his ongoing story. A belief that Peter Parker can never be too happy, or it ceases to really be a Spider-Man story, as if Great Tragedy is the only thing that could possibly inspire Great Responsibility. Greg Conway, the writer behind “The Night Gwen Stacy Died,” has said as much. Talking about how happy Gwen and Peter were together, he says, “But that’s not what Spider-Man is about. It’s about pain and power and the responsibility that comes with it. There’s nowhere to take the relationship without betraying what Spider-Man is all about.”

This is a concept that Across the Spider-Verse grapples with directly. While in Spider-Man India’s universe, Miles directly interferes with something the movie calls a “canon event” by saving the life of a police captain with personal ties to that Spider-Man’s alter-ego, Pavitr Prabhakar. Later, Miguel O’Hara, the head of the multiversal conglomeration of Spider-folk (also known as Spider-Man 2099) explains the situation to a confused Miles: Every Spider-person, in every universe, has had to come to grips with a personal tragedy that defines their heroism. The same story plays out, again and again, across the multiverse, thousands of times over. Without that tragedy, not only are the Spider-heroes not truly Spider-heroes, but their entire universe destabilizes, swallowed up by the darkness into nonexistence.

Whether that’s a metaphor for editorial fiat or a respawning belief in comics creators, the meta-metaphor is clear. The belief that with Great Spider-Man Stories there must come Great Tragedy is a powerful force that may seem impossible to resist. The belief is that bringing happiness to a Spider-Man — or even superheroes in general — summons a kind of entropy. In the real world, the belief seems to go, this manifests as a decreased interest in a comic book, leading to waning sales, leading to cancellations. And once a character’s story is no longer being told, can that character truly be said to exist? Once that belief takes root, there’s only one clear way to keep Spider-Man, and the universe he resides in, alive: pour on the tragedy. No matter how poorly it is written.

And it’s been written very poorly indeed. Comics have gone to elaborate lengths to keep Peter Parker unhappy, each one more ridiculous and less interesting than the last. Actors hired to simulate his wife’s death, a deal with the devil to undo his marriage, a forgotten extradimensional god in a chronologically unstable universe both ending his chances for love and killing Kamala Khan in one go. It doesn’t seem to matter so much how these tragedies must happen, so long as they do. The same story, over and over again, with just enough variance for creative teams to believe they’ve kept things interesting.

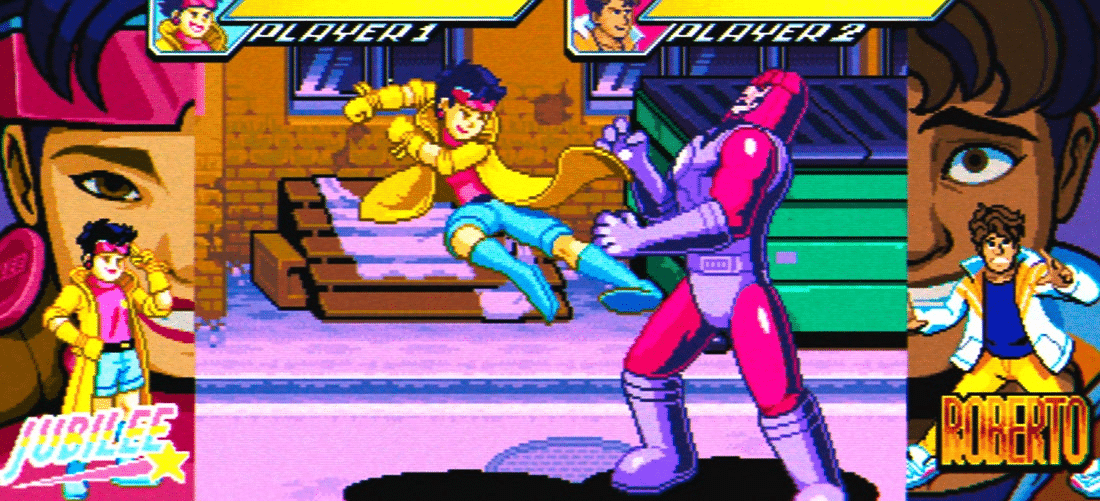

Miles Morales rejects this idea (So does Hobie Brown, Spider-Punk, but to be fair, he rejects everything). He’s rather unique in the Spider-Verse, as a Spider-Man with two living, deeply loving, parents. He has a future ahead of him, and more excitingly, the promise of new stories, and new ways to tell them. He fights with everything he has, against every kind of Spider-person imaginable, for a chance to tell those stories.

Let’s move away from the comics, and take a quick look at other Spider-Man stories that have captured people’s imaginations over the past several years and revitalized the fandom in a way the comics haven’t even come close to doing. We have the Spider-Man video games, of which Miles Morales is an important part. The Tom Holland MCU movies, which themselves borrowed many elements from Miles Morales’ story that were essential to their success. Lastly, of course, there are the Spider-Verse movies, placing Miles front and center and setting new benchmarks for storytelling in both comics universes and animation in an entertainment landscape desperate to play it safe and tell the same stories over and over again for the sake of their bottom line.

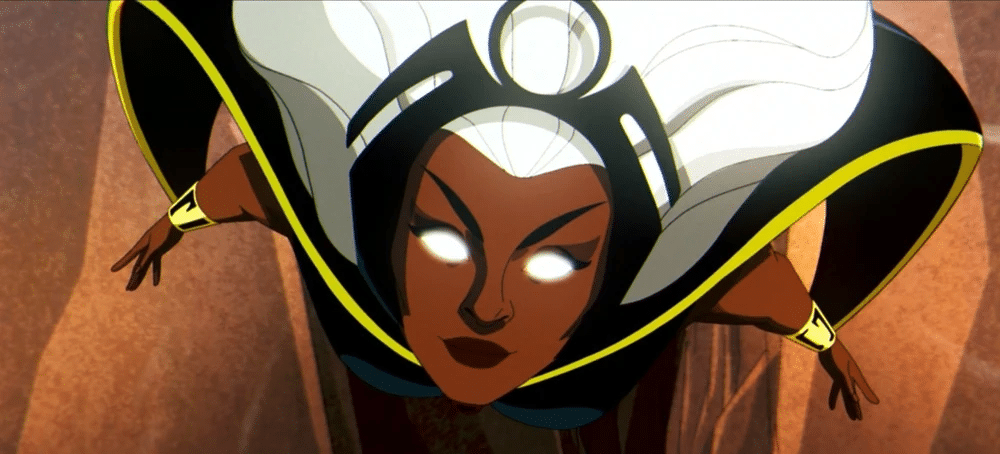

It’s clear that the Spider-Verse movies have a lot of love for their source material, acknowledging their comic-book origins like nothing before. The latest movie takes this to a new level: crossovers with multiple art styles and coloring choices, distinctive lettering for individual heroes, thoughts appearing as captions, playing with panel layouts, heck, even the odd editorial note or two. It takes the best of what comics can do to tell a story, acknowledges the variety of ways they have done so, and does something new with them. It acknowledges comics’ darker side, too — the unwritten rules that shape their repetitive stories — but it refuses to be bound by them. Miles Morales, and the movies themselves, accept the legacy they’re taking on, but they refuse to let that legacy dictate what kind of story they can tell.

Into the Spider-Verse and Across the Spider-Verse, in short, prove that new Spider-Man stories can be told — and that they can be told spectacularly. Where the first film revolved around the simple concept that accepting a legacy doesn’t mean you can’t wear it your own, unique way, the second film takes that concept and lets it grow. Miles struggles with the loneliness of an unconventional path, of being an anomaly, of not quite fitting in even with the people who share his abilities, and his unique view of the world. He is an anomaly — but no matter how much that destabilizes things, it’s something he holds onto with everything he has.

Comics characters are rarely allowed to grow, and no matter how many new takes by inventive creative teams happen, they’re barred from true change, dragged back to familiar patterns in the mistaken belief that that’s the only way to keep their stories alive. Look no further than Marvel’s upcoming Fall of X storyline, which threatens to undo the biggest change that’s ever happened to the X-Men, that’s made their comics more exciting to read than they have been in decades.

What Miles Morales represents is the possibility of growth. Not just change for change’s sake, but taking everything that has come before and doing something new and exciting with it. A belief that stories don’t need to be beholden to a certain pattern, that they can evolve into something worth following along.

The end of Across the Spider-Verse leaves many things unresolved, and one of the biggest questions is how Miles will find a way to thread the needle — to be Spider-Man and keep tragedy from entering his story. Beyond the Spider-Verse will center on Miles’ fight for a better story, and a belief that there can be a better story is vital if superhero stories are to mean anything at all in the long run.

Without that belief, Kamala Khan will keep dying, over and over again, to uphold a story that nobody’s happy with — and she won’t be the only one.