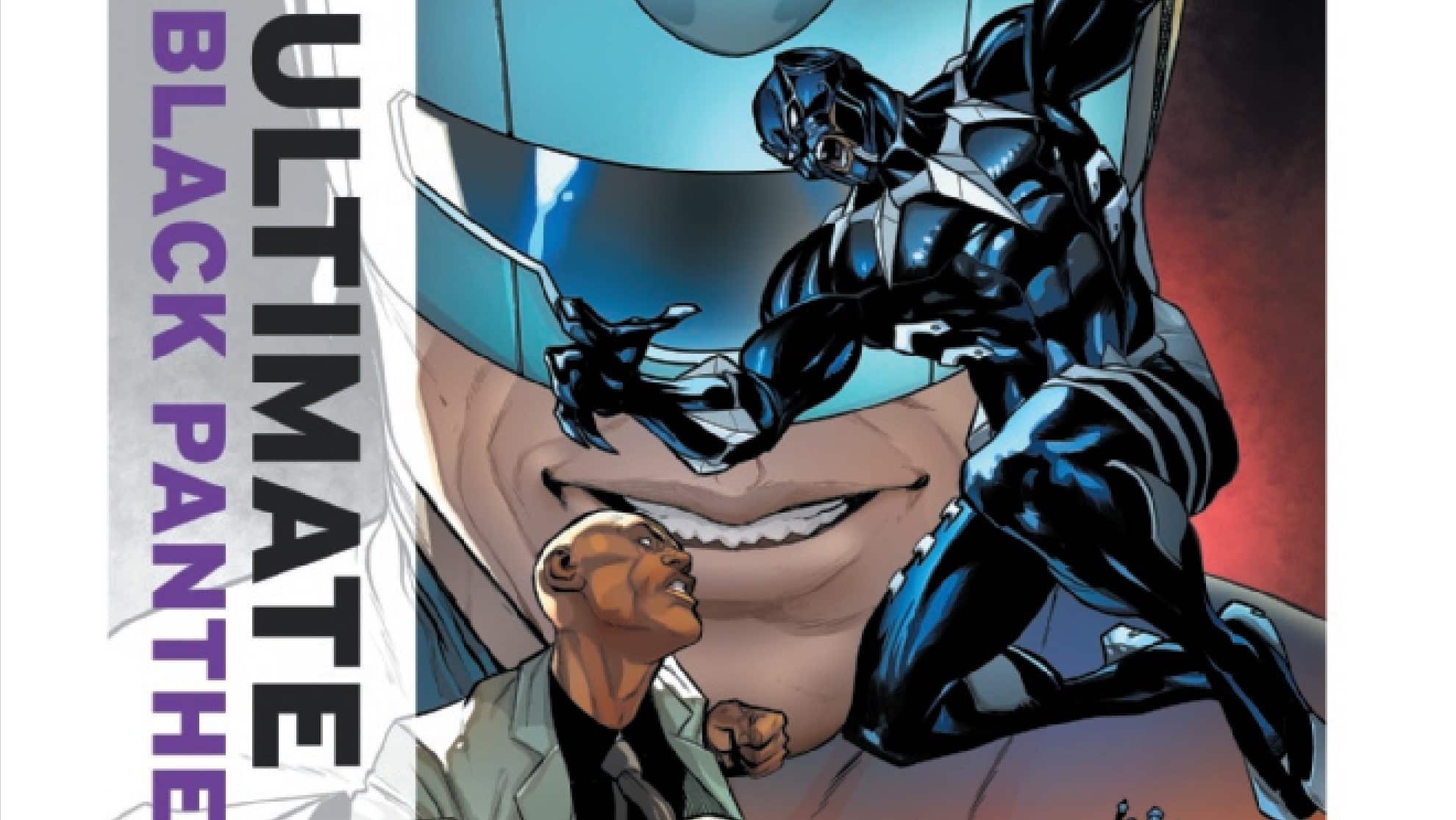

The five crime families that rule Birnin T’Chaka have heard the rumors that the Black Panther is lurking in the shadows, so they bring in a hired gun to help protect their interests: the cyborg assassin known as Deathlok. Black Panther #3 is written by Eve Ewing, drawn by Chris Allen and Mack Chater, inked by Craig Yeung and Chater, colored by Jesus Aburtov and lettered by Joe Sabino.

Escúchela, la ciudad respirando.

The main character of Black Panther #3 is not, well, the Black Panther. Not his King-in-Exile alter-ego, nor his gazelle-named nemesis.

Not his sister, nor his family, nor the ruling government.

The main character of Black Panther #3 is the city.

And the city, a living, breathing being in its own right, has a story to tell about itself: those who inhabit it, and those for whom the dream of Wakanda, much like the American Dream, is more projection than reality.

As important as character design is in a comic — making sure the heroes readers idolize look idolization worthy — is the design of the worlds those characters inhabit. Those details matter, and to great effect, the art team of Chris Allen and Craig Yuen and colorist Jesus Aburtov have done a masterful job of creating a hustling, bustling but decidedly non-decadent metropolis.

The city of Birnin T’Chaka — its character, its personality — dominates every page, from its claustrophobic and light-strobing cityscape, to its cramped, overstuffed apartments. Its imperfections in the story give reason to T’Challa’s presence, and its manifestation on page continually reminds you that his presence is needed.

Take, for instance, Beisa’s (or, since we now know her given name, Natima’s) apartment. We were told earlier in the series that Wakanda’s people do not need the basics: Food, clothing, shelter are provided for all. Life, of course, is much more than the basics. Thus we see a simple, small apartment, lit by the bustling amber streetlights of the city outside. We see books upon books (She is well read); we see art and artifacts (Things she appreciates? Things she’s stolen?) We learn from her mouth (and T’Challa’s research) that she takes from the city’s crime lords, using expertly crafted vibranium weapons to aid her Robin Hood-like cause.

She is not educated, but she is intelligent, and her intelligence is tangible in her space. Thus, when she throws one of her expertly crafted artifacts at T’Challa, proving he’s not some imposter in a suit, we wonder: Was her act a wild provocation or preplanned test?

Or take the Kitu Market, where T’Challa’s image inducer allows him the freedom to walk among the people as a laborer with prosthetic legs. Our image of Wakanda, from movies, other comics — from our hopes, our minds’ eyes — is a place of gleaming plenty, of Afrofuturism and abundance.

Not a place where wires hang and trees are scarce and manual labor is necessitated. And yet, that’s what readers are greeted with as they’re introduced to T’Challa’s day job. There is no opulence or abundance as he listens in on rumors of an arranged wedding between the formerly rich Aliya family and the crime-funded Nkisu. The streetscapes and skylines are reminiscent of marketplaces in South Asia, or the weathered futures of Blade Runner or Cowboy Bebop — places filled with people, but not necessarily much capital, or hope.

And of the people? A city is nothing without citizenry, and the dress of the citizens says just as much about the city as its landscape. None of the people have anything ornate on them — no jewels or fancy watches, but also no exuberant colors or styles. Form follows function, and the people, like the cityscape, are built for maintenance, not exuberance. Even the lackeys, sent from the Nkisu family, to (impolitely) request a last-minute meal from the restaurant that serves as T’Challa’s cover, look decidedly plain. T’Challa’s reflexes (misinterpreting a reach into a coat pocket as a threat) earn him an audience at the wedding, where he and his now partner in crime (or crime fighting!) plan to infiltrate the affair to learn more about the consolidation of crime-lord power.

Even in this setting, in what must be the most opulent of places and spaces in Birnin T’Chaka, note how *close* all the buildings still are. Not how *close* all the people are in what must be a grand meeting space. The intimacy of the venue, of course, allows for more opportunities for action and expression, but also subtly points to another truth: Even the most extravagant of structures in this place operates under the constraints of humility and lack.

The initial plot point of Tochi Onyebuchi’s just-wrapped Captain America: Symbol of Truth (Cap with wings, not the defrosted Cap) focuses on a group of Harlemites seeking asylum and acceptance in Wakanda under the purposefully enticing mantra “Wakandan Forever.” Alluded to but not explicitly said, Black Americans, looking for a better life than America has ever promised or provided, tried to emigrate to a promise of abundance and admiration.

And while this plot point was wrapped up too quickly and cleanly (Sam Wilson goes to Wakanda without permission, gets in a fight, gets kicked out along with every other Black American trying to get in — a premise that deserved a series in itself, as opposed to the single panel of resolution that wrapped the plot), the implications — that the promised land exists — still hold strong resonance.

This comic, then, breaks that resonance down into startlingly familiar reality. Even Wakandans dress humbly. Even they have crime lords, acting as an interim government in a place that’s felt all too ignored since it’s no longer prosperous.

Even Wakanda can get infiltrated by a Deathlok, killing attendants and requiring an appearance from a fully clothed (and God, what wonderful clothes!) Black Panther.

Writer Eve Ewing made clear she wanted to create a rust-belt like analogue, a place where people struggle to get by and feel unseen by their more opulent betters.

She’s succeeded, in so many ways, which not only makes this iteration and issue of Black Panther an engaging read, but a (sadly) familiar, relatable one as well.

Disclaimer: As an Amazon Associate, ComicsXF may earn from qualifying purchases.

A proud New Orleanian living in the District of Columbia, Jude Jones is a professional thinker, amateur photographer, burgeoning runner and lover of Black culture, love and life. Magneto and Cyclops (and Killmonger) were right.

Find more of Jude’s writing here.