Click here to read Part I. Click here to read Part II.

Sometimes a year’s worth of comic books feels like a day, and sometimes a day feels like a year. Our first two parts of this three-part look back at Grant Morrison’s New X-Men (2001-04) were written and edited before Fall of X (2023). This last part was written afterward, and it covers the issues where Morrison themself — so they’ve said in later interviews — felt frustrated, even thwarted by Marvel higher-ups. It’s hard not to see that frustration in Morrison’s last arcs. It’s hard not to see, too, the way these arcs speak to fans now: It’s a mess, they say, and you’ll never get just what you want from a world that wants to preserve the status quo. You can give up, if you want. But you can also choose to stay with it, loving these characters — as some of them love one another — not so much for who they are as for how far they’ve come, and for who they might be.

New X-Men #141 concluded by solving most of a mystery: Who killed Emma Frost? Beak took the blame to protect Angel Salvadore, who wasn’t at fault, because she was mind-controlled by Esmé Cuckoo, who ran away from the mansion, and from her sisters, promising she would show them all when the coming era of mutant supremacy arrived. Meanwhile, Jean brought Emma back from the dead, using her gathering Phoenix powers, and thus putting her husband, Scott, back in a position where he would have to choose between Jean — his wife of who knows how many years — and Emma, his recent partner in telepath sex.

New X-Men #142 involves just one of those characters, at odds with himself. It’s also at odds with familiar cape comics genres, because — as he’s done issue by issue before — Morrison picks a new genre to emulate: In this case it’s an “adult” comic, one with big panels, low light and sexy ladies, set in a place — a stripper bar! — where sex is on the menu. With its leather outfits, whole-body poses and burgundy-orange palette, the issue looks a lot like Sunstone, Stjepan Sejic’s high-quality NSFW comic about BDSM, launched in 2011. Scott, drowning his sorrows in alcohol, rejects a stripper (at the Hellfire Club, we later learn) who emulates Emma emulating Madelyne Pryor emulating Jean. “All our dancers are telepathic tonight,” explains a typically smug Sebastian Shaw.

As usual, Logan knows what to do when (and only when) nobody else does: The near-immortal mutant with the nearly unlimited healing factor gets his best friend to drink till he passes out. Mutants take care of other mutants, even when they’re bro’ing it up. It’s hard not to see triangular desire between Scott and Logan: Their way to be together involves rivalry over Jean. Having pulled out every deep red, burnt pink and orange digital shade in his digital palette, Chris Chuckry gets to remind us what’s really at stake (and how men look with no women around) with two pages of contrasting black and white and tan showing Sabretooth taunting Logan at the club’s urinals.

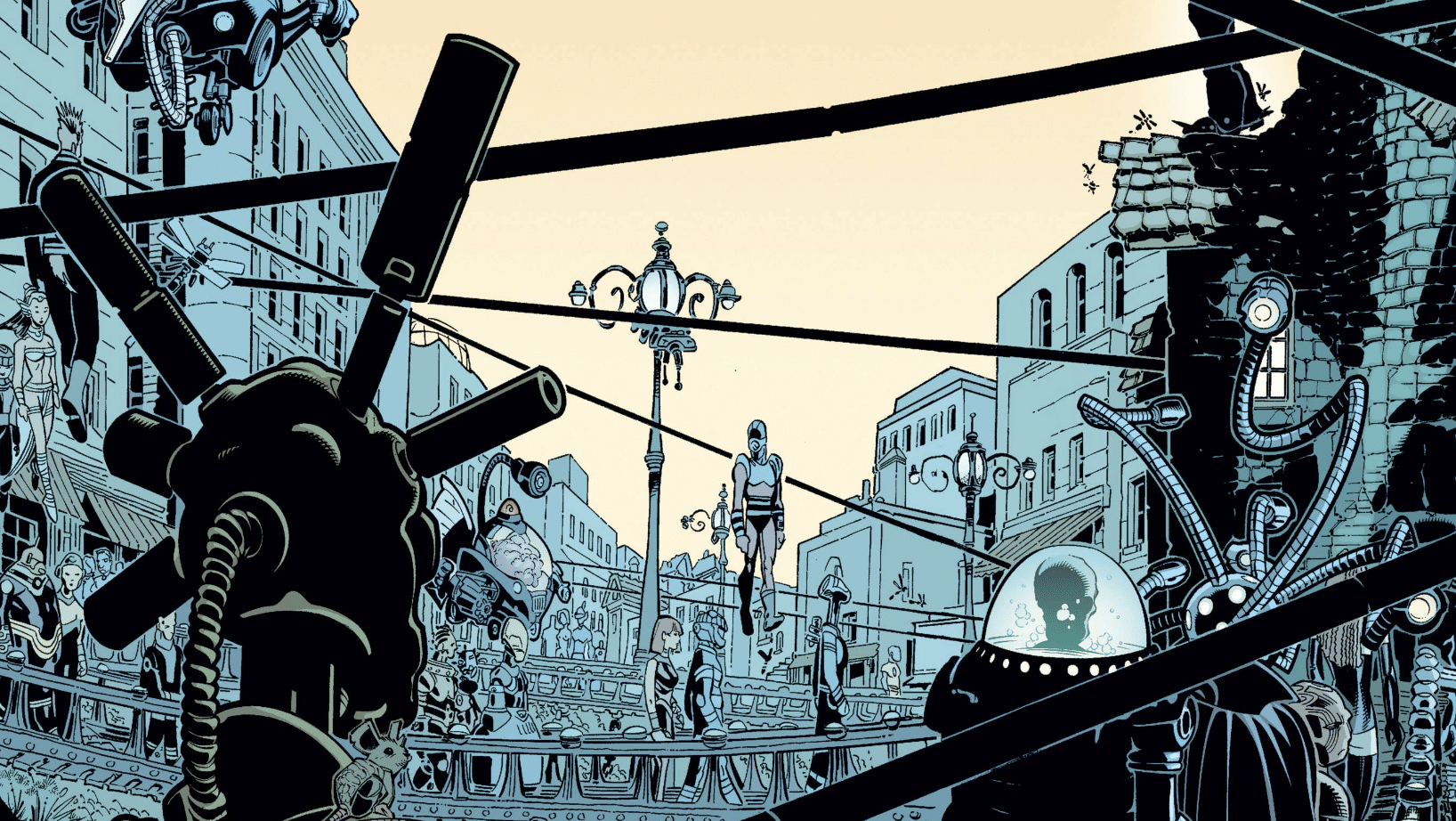

Then it’s time (See what I did there?) for New X-Men #143-145, mostly set in The World, birthplace of Fantomex and much else; here “time is completely under our control,” as one bad guy says — he might be describing the medium of comics, which famously turns time into space. The World is a “Petri dish” for experimental mutant bodies and powers, a “micro-reality” where new life forms can arise, and flourish, and fight, and die out. It’s also a showcase for Chris Bachalo, who gets multiple full-page canvases on which to draw weird machines, and weirder architecture, and horror-goo. Lightning forks over ruined futuristic cityscapes. A toothy flying cybernetic killer whale with one tentacular eye turns out to be a “car-cop. … Aim for the control chip!” Logan (aka Weapon X) gets the promise, but not the reality, of the truly true this-time-it’s-not-a-fake-memory truth about his early life. The point is the art, and the chance for Morrison to go all-out on J.G. Ballard-esque Weird Fiction worldbuilding before they have to land the big plot plane.

Or spaceship. New X-Men #145 finds Weapon XV with Wolverine in space, Scott and Fantomex in The World. It’s one last chance for Bachalo to draw full-page spreads, with asteroids and a partly built space station and loads of the De Luca Effect. And it’s the start of the full-on meta-comics. Scott complains that fighting this arc’s big bad felt “like running a fight program … like pro wrestling.” Maybe none of this is real! Maybe it’s propaganda, as Fantomex says, “disguised as a comic book fighting team,” based on market research, giving the viewers of Saturday morning cartoons “corn they can understand.” Maybe it’s time to blow the whole thing up.

That’s where Scott Summers comes in. As Beak gets less important — as Morrison’s New X-Men turns into a book about adults — Scott becomes the primary reader figure, the one who cares about the outcomes, whose powers (though groovy) can’t simply rewrite reality, who’s not de facto immortal, who can’t help taking everything seriously. He’s the one who’s most like you, reader, and most like Morrison, the writer. And he’s the one who’s going to have to decide whether he, and we, still care about the X-Men after his world’s been smashed to bits, again.

Not only does the series develop a moral center, it also goes hard on its major claim about morality: Don’t tell people what to believe, and don’t try to make them do what they won’t choose to do. Xorn, who’s about to reveal himself as Magneto, gives the game away when he tells Professor X that Dust “refused to renounce her religion,” and that’s why he trapped her in a jar. But Xorn also tells Professor X what’s wrong, in effect, with company-owned cape comics: They’re, at best, an endless chain of attempts to do something new followed by canon resets. “You’ve had it all to yourself for too long and nothing much has changed, has it, Charles?” He’s not wrong, and the space explosions that follow — underneath campy, exclamatory, bright red lettering (“MAGNETO SET US UP!”) — put a pin in his point.

Here comes the part people hate. Xorn was really Magneto, maddened back into Silver Age evildoer status after the earlier destruction of Genosha, a mutant supremacist once again, without regret or apology. “Magneto Superior.” He’s a straight-up jerk, and his Silver Age personality matches the impressively craftsmanlike — and more conventionally superheroic, as against Bachalo or Frank Quitely — pencils of Phil Jimenez. Having used Esmé Cuckoo and the rest of his stigmatized teen class to his own purposes, Magneto (Don’t call him Erik, or Xorn, anymore) will now concentrate on destroying the human world and erecting “New Genosha,” for mutants only, on the ruins of Manhattan. “BROTHER MUTANTS! THE GREAT DAY HAS COME!”

If you want to see why some writers like mixed-case lettering, here’s why: It can make someone super-bombastic, or loud, by contrast, with all caps. The master of magnetism speaks in all caps for four consecutive pages. My ears hurt. And he’s talking, this time, not so much about the mutant metaphor, nor about real persecuted minorities, but about the feeling that he, and we, and Morrison, are trapped in a comic book. While Morrison gives Jimenez and his art team a real workout, destroying detailed infrastructure amid a plethora of crowd scenes, Magneto and Esmé agree to denounce … comic book fans. “They lose interest so quickly now,” he muses. “I can barely finish a sentence.” And Esmé agrees: “They have short attention spans and high expectations. They want to see the world’s most charismatic terrorist at the height of his powers. They want you the way you used to be.”

And that, folks, is why Stan Lee (supposedly) said that fans only want “the illusion of change.” They also want callbacks: for example, Logan showing feelings for Jean Grey, and Jean Grey apparently dying as she and her spaceship — again — approach the sun. Is anything in a cape comic really new? Or is every new emotion, idea, plot point and character design really just ’60s Magneto in a Xorn hat? In space, in New X-Men #148, the fans perhaps get what they want: Jean and Logan, with Logan Shatnering around — how long did it take Jimenez to draw every hair on Wolverine’s arms and chest? — and Jean stripped down to her bra, and the two of them embracing at last. The male gaze and the female gaze, the heterosexual and the very queer gaze, as well as people who just admire blocking and layout and cool use of negative space, get something to see in this visual medium, while Morrison revs their story toward a final, meta-comics-y confrontation.

That confrontation will set the power-mad against the almost laughably naïve. Magneto has lost the thread so badly that he’s setting up “crematoria.” Beak and Angel understand what’s wrong: “There is nothing new about people marching into the ovens.” Magneto desultorily quotes George W. Bush: “With me or against me — make your choice.”

Turns out the with-me-or-against-me, evolution-has-a-direction philosophy behind eugenics — control over other people’s bodies, over their reproductive choice, over the genetic makeup of the next generation — unites all the villains in the Morrison run, from AIM and the people who built The World to Magneto to Cassandra Nova to John Sublime. Opposition to eugenics, the wish to construct a society where your body is yours and you decide what to do with it, unites everybody that Morrison wants us to like. Sounds good to me.

There is no good or appropriate way for this plot to end. “It’s boring and old-fashioned,” as Martha and Ernst together tell Mags. The Phoenix Force feels like the embodied, self-aware consciousness of cape comics as such, making sure that the popular characters come back from the dead, that the lights stay on, that people keep watching, and why not? “It’s bloody Jean, showing off again,” Emma complains. Then Emma’s glamorous, rebellious pupil Esmé, Magneto’s ex-acolyte, completes a would-be triple-cross, the end of Morrison’s attempt to rewrite The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. “I thought you were special. The greatest mutant who ever lived. … But you’re just a fossil,” Esmé tells the man who ruined her life, before he ends her own.

The Morrison run is not the first place I go for feminism. In fact, it barely passes the Bechdel test, since most of the long conversations between grown women are Jean and Emma discussing Scott (“This is going to be one hell of a test,” as Scott says in another connection). That said, the affair, or romance, between Esmé and Magneto works out about as well as affairs between students and teachers ever do: “HOW COULD YOU BE ANYTHING TO ME BUT A MEANS TO AN END?!” he blows up at her. And Esmé redeems herself, albeit in death.

Poor Esmé. Poor Emma. Poor everyone. “I will not be judged by children,” the would-be planet-ending master of magnetism insists. But in a comic book — and maybe even in real life — the next generation, the naïvely hopeful, the ones who haven’t been ground down yet, are the ones who should judge. Are we giving them power to figure out who they are later, or locking them into a future they never chose? Shirtless, resurrected Logan knows what to do. So does Emma, who wants nothing more than to be a good teacher. And so does Jean, who sacrifices her life, once again, to save others. “I haven’t seen you so alive for a long time, Scott. … Live, Scott. Live. All I ever did was die on you.” And then: white space.

Morrison’s done being told what to do. They’re almost done writing the present day of the X-Men. They’re done with the figures who want to control everybody and everything, for money or for kicks or for a hit of Kick, in 2004. And they’re done — that’s how it feels — writing Marvel characters they no longer control and cannot change, with the single exception of Scott and Emma, the most serious plotline in the whole Morrison run, the throughline, the one that won’t get undone for nearly 10 years, and the one that resonates — again — with anybody who’s ever discovered their true self, or their sexuality, or fallen in love, online.

Scemma. Autonomy vs. eugenics. Metacomics and anticorporate protest. Letting the artists do what they do best. Genre-hopping (up until “Planet X”). Weird kids with visible disabilities becoming the heroes (especially Angel and Beak). And did I mention Scemma? Those are the legacies of the Morrison run. So, as we’ll see, is a kind of hope in the property, in these company-owned, long-lived mutants, even when they’ve taken a very wrong turn.

To get to that hope, though, we’ll have to swim, fly and crawl our way through “Here Comes Tomorrow,” drawn by Marc Silvestri, whom X-fans back then would have known from his run on Wolverine, as well as from his end-of-the-Claremont-era heroics. “Planet X” looked (among other things) like Morrison’s objection to the way that working for Marvel (or DC, or Disney, or really any big company property) sooner or later ends with the company calling the shots. “Here Comes Tomorrow” looks like the objection to the objection. Set in a new dark future — literally dark: The sun never seems to come out — the story lets Morrison do whatever they want to do with a handful of new characters, plus the near-immortal Wolverine. It lets them cut loose, in terms of continuity, while letting them tie the story to an entire ship’s rigging worth of throwbacks and callbacks. The Age of Apocalypse. Dark Beast. The original “Days of Future Past.” Uncanny X-Men #138, with its so-often-referenced cover, in which Cyclops sorta kinda quits the team.

At the same time, it lets Morrison manipulate a brace of never-before-seen, never-again-seen characters, starting with Tom Skylark, a somewhat Scottish-sounding stand-in for the reader and maybe the author. Can Tom fend off the future that this white-haired, grim-souled, Sublime-possessed Beast would like to create? Can anyone? That future looks like a spectacular, thumbs-down judgment on the present, “the judgment of the Phoenix,” as the grown-up three-in-one Cuckoos, hooded like Fates or Sybils, explain. Silvestri and his team (four colorists worked on New X-Men #154 alone!) present that judgment in spectacular, detailed fashion. The story has more explosions, more flight, more oceanic splashes, more splash pages, more special effects that would cost a gazillion dollars on film. Cape comics excel at them, even as they also give writers like Morrison, at their best, room to experiment. U-Beast, like a controlling corporate office, stands “alone against this tide of gross creation,” wanting to standardize all life under his control, a “final purification of things.” He wants power over the next generation, from people to termites to whales, such as “Mer-Max of the X-Men,” who also sports what appears to be a Scottish accent, “tired and sore and oot o’ porpoise jokes.”

If Morrison is thinking about ethics and society, they’re proposing that a good world allows for the weird, and a bad one stamps it out. And if Morrison is making metacomics — and they are — they’re getting one last series of blows in. “The supermen fight and die and return in a meaningless shadowplay,” U-Beast tells his henchman, “because we make them do it.” That’s every canon reset in the history of cape comics. It’s X-Factor, Vol. 1, No. 1, and Jim Shooter making Scott Summers leave his wife and child. It’s Joe Quesada demanding that the number of mutants get cut down from millions to 198 on M-Day, because readers wouldn’t sympathize with anything but “a tiny, persecuted minority.” It’s every time you’ve committed your heart and bones to a long-form serial that fails to stick the landing, or to a new status quo that snaps back to the old. And it’s a reminder that — to quote Douglas Wolk at the end of All of the Marvels — a corporation will never love you back; a story will never leave you.

Or, to quote Jean as the Phoenix Force in Morrison’s final issue: “It didn’t deserve to end like that. My friends deserve better.” They do, and they always did. They still do. And there is, as a futuristic robot descended from Fantomex’s spaceship tells Jean, “No en//d ye///t.” As the Australian comics critic Leon Miller wrote in 2021, Morrison concludes with “a pointed critique of comics’ cyclical limitations” and a way out of them: do something so impressive that almost nobody wants it walked back.

What thing? The revitalization of Scott Summers, and his long romance with Emma, and the life-in-death of Jean, who takes advice from a kind of interdimensional Green Lantern-cum-Captain-Britain-cum-Phoenix Corps before — apparently — inspiring her ex to un-quit the X-Men and get back together with Emma, so that the series concludes (Live, Scott, live!) with a kiss.

Those twilit last two pages of Morrison’s run resolve the soap-opera triangle at its center, handing the X-Men and their stories on to “a new generation of gifted bloody brats.” These mutants aren’t Morrison’s, nor are they Marvel’s, the ending says. Maybe the humans will always “want to kill us,” maybe “nothing we do makes a difference” to big corporations and voting publics, but we’re not there for them: We’re here for one another, and for the next generation. Mutants, like many real people, may be in school, or out of school, or in some alternate future not yet drawn, and they may never be secure or lastingly happy or content, but their stories can always go on, and if we want them, their stories belong to us.

Disclaimer: As an Amazon Associate, ComicsXF may earn from qualifying purchases.

Stephanie Burt is Professor of English at Harvard. Her podcast about superhero role playing games is Team-Up Moves, with Fiona Hopkins; her latest book of poems is We Are Mermaids. Her nose still hurts from that thing with the gate.